Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Tuesday, 1 March 2016 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The ironies inherent in the regular lambasting of the so-called free media by the political establishment, particularly when ensconced in power, and the media’s inevitable self-righteous responses, will not be lost on any independent observer. Criticisms levelled at one could just as easily be thrown back at the accuser. After all, in the way they have evolved here, the two institutions are very similar; they could well be a mirror reflection of the other, twins; discredited, self-promoting, mediocre, yet with an iron grip on our collective consciousness.

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe. The ironies inherent in the regular lambasting of the so-called free media by the political establishment, particularly when ensconced in power, and the media’s inevitable self-righteous responses, will not be lost on any independent observer

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe. The ironies inherent in the regular lambasting of the so-called free media by the political establishment, particularly when ensconced in power, and the media’s inevitable self-righteous responses, will not be lost on any independent observer

Politician is top dog

There is no question that in the power hierarchy of our country the politician is top dog. Without his patronage, nothing has value. Even very private functions, a wedding, a funeral, a felicitation, has ‘cultural’ meaning only with the participation of the politician. Only he can bring legitimacy or social recognition.

The laws, systems, and traditions – they are secondary. What matters is what the politician wills. When the politician wants his friend to be awarded a government tender, the friend’s tender will be the best qualified bid. If he wants a road to go over his opponent’s land, that route will become the most efficient direction for that road to take. Only he knows best where to locate an airport or a sea port.

When the politician decides to call this country the “little miracle”, so it will be a “miracle”. A few months later he may consider “little miracle” too modest a description of the land on which he bestrides, and that the country ought to be promoted instead as the “wonder of Asia”. Now, the “little miracle” will quietly transform into the “wonder of Asia”, almost unnoticed, seamlessly. Such power is not to be taken lightly in the context of the society where it thrives.

The country lives hand to mouth, sustained formerly with Chinese largesse and now with a billion dollars deposited by a benevolent man from Belgium. A little trouble in a major tea buying country sends the economy into crisis mode.

Falling oil prices mean less employment in the Middle East, an unnerving prospect for the millions depending on remittances of our workers there. However, for those who think in terms of living in “miracles” and “wonders” these are not huge concerns.

After all, progress as per modern definitions is conceptually irrelevant, especially when we have been there centuries before, conquering not only the land and the sea, but even the air. In pre-historic times, when in other places homo-sapiens were battling it out with the Neanderthals; our ancestors were using flying machines! Facing the truth, understanding reality, making a correct assessment; that is another country.

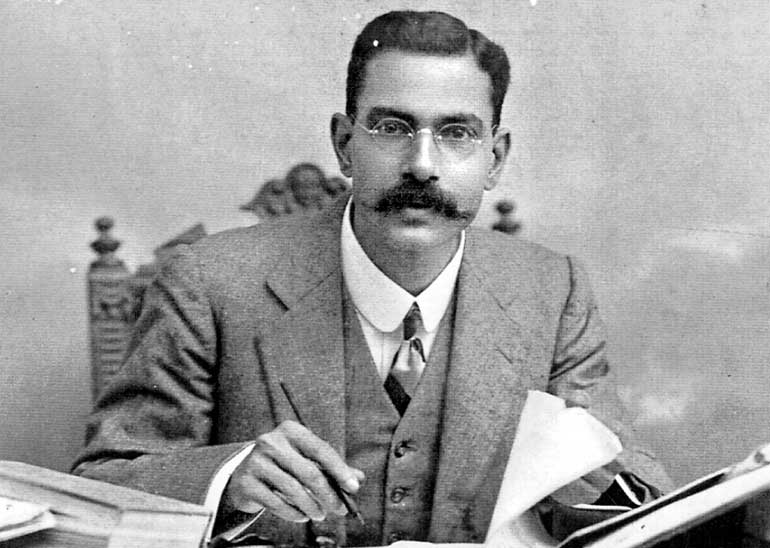

Armand de Souza took on the might of the British Empire on behalf of a people who had been grievously wronged. He was followed by a series of brilliant journalists, who in various ways uplifted the standards of public discourse

Armand de Souza took on the might of the British Empire on behalf of a people who had been grievously wronged. He was followed by a series of brilliant journalists, who in various ways uplifted the standards of public discourse

Journalism in Sri Lanka

Like in politics, in this country, journalism calls for no particular background or training. Anybody can be a journalist like almost everybody is in politics. Entry, relative to other professions, is easy, and the skills required only basic.

Like his politician counterpart, the journalist, by and large, has no permanent friends or enemies. Many of them, at different times, have worked for media institutions with diametrically conflicting ideologies or allegiances. Sometimes they even return to the original  institution having damned its stand only the week before. One journalist wrote an admiring biography of a politician when there was every chance that he would end up on top. That did not happen. Now he is critical of that politician at every turn.

institution having damned its stand only the week before. One journalist wrote an admiring biography of a politician when there was every chance that he would end up on top. That did not happen. Now he is critical of that politician at every turn.

It is quite common today for a journalist of one newspaper to be a news reader on a TV channel owned by another company. Although the print media (newspaper) may be distinguished from the electronic media (TV channel), it cannot be denied that the stock in trade of a journalist is news (and views) he holds. Which media house gets the benefit of the man’s knowledge and efforts? Who does he serve best and which ideology does he endorse? Can the resulting situation of conflict be so blurred that it can even be ignored? After all, when it comes to the news, the public is entitled to know who is saying it and why.

"It seems that the media (print/TV/web-sites) has now become a vast scheme to beguile the unwary in the sense that while posing off as independent, they are in fact owned/controlled directly or indirectly by major players in the political field. If the corporate veil can be raised or the money trail followed, the truth will emerge"

Fundamental function of a journalist

A fundamental function of a journalist in a democratic society is to provide critical analyses of the government. Governments are not run by divine or infallible creatures. And every cent they use belongs to the community. The media’s role is to keep our rulers in the straight and narrow.

Not so long ago, we saw the Government becoming a godfather of journalists, offering itself as a primary sponsor of journalistic welfare, showering certain journalists with honours, benefits and even gifts. They did not think this amounted to influence peddling or even outright bribery. From being one of the pillars of the State, the ‘Fourth Estate’ downgraded itself to a pitiable recipient of welfare. The government, the very institution they had to examine critically, that which is most open to corruption, and most inclined to abuse our rights, became a source of patronage and reward for the journalists.

Today, journalism only attracts the very young or the callow, leading to superficiality in most writings. Political realities of the present are the result of long-drawn-out and complex historical and social processes. But most of those who write on politics now are ignorant of the evolution of these issues and therefore simply equate their function to interviews with a politician, giving inaccurate or partisan reports of a related incident, or simply repeating gossip from the street.

Even in business reportage, one is left with the impression that the financial sophistication of the young journalist ends at crossing a cheque. In other countries, the business world and investors await the business pages for objective and professional analysis and guidance. But in our business pages, such reports are invariably mere reproductions of an Annual Report of a company or an interview with the CEO of that company, not the best sources for objectivity!

It seems that the media (print/TV/web-sites) has now become a vast scheme to beguile the unwary in the sense that while posing off as independent, they are in fact owned/controlled directly or indirectly by major players in the political field. If the corporate veil can be raised or the money trail followed, the truth will emerge.

Even the few media barons not directly involved in politics do not hesitate to leverage their news organs in ways which would be frowned upon in a more evolved system. Propaganda in the guise of news and views is being fed to a public who cannot tell chalk from cheese. In the absence of laws or even effective guide lines to regulate media ethics, its control by interest groups, directly or indirectly, leads to the undermining of a vital pillar of democracy.

The way we were

Like in politics, in journalism too, we can now only think of ‘the way we were’. In the early 20th Century Indian-born Armand de Souza (father of the renowned LSSP ideologue and university don, Doric De Souza) settled down in Sri Lanka and became the Editor of ‘Ceylon Morning Leader’.

The brutal and unjust suppression of the Sinhalese people in the aftermath of the riots of 1915 by the British Colonial Government moved him to produce the famous ‘Hundred days in Ceylon’. Souza prefaced his book with these opening lines:

“This book is an appeal to the British conscience for justice to the people of Ceylon. I believe it will justify my faith. Bred, though not born, one of them, I have known the people of Ceylon for over thirty years and chosen to make their home my own. I may fairly claim to be free from any partiality for any particular community, or interest in any particular race. My ordinary work affords me uncommon opportunities of appreciating their virtues and observing their failings, and I have not insisted upon the former more than I have criticised the latter in the course of my daily contributions to public opinion in the island.”

Here was a journalist taking on the might of the British Empire on behalf of a people who had been grievously wronged. Armand De Souza was followed by a series of brilliant journalists, who in various ways uplifted the standards of public discourse – Tarzie Vittachi, D.B. Dhanapala, Janze, Hulugalla, Mervyn De Silva, among several others, are names that the Sri Lankan media can take pride in.

Where such men once flourished is now a barren land, occupied by journalists whose life ambition is to receive a gift of a plot of land or a duty free car from the government. As famously quipped by Churchill, reading of the newspapers of today offer neither pleasure nor profit.

Meanwhile, the politician too has failed completely, for the millions making this country their home, the Promised Land is now only a broken dream. If all what has happened since 1948 is the best that our political leadership could have produced, unless we adopt a completely new philosophy of leadership, there is not much hope.

The links and the similarities between the political establishment and the media, unspoken of, yet very real, bring to mind the concluding paragraph of Animal Farm, that brilliant political satire of George Orwell: “Twelve voices were shouting in anger, and they were all alike. No question, now, what had happened to the faces of the pigs. The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again: but already it was impossible to say which was which.”