Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday, 23 November 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

I was reading a paper written by a Sri Lankan scholar living in the United States which had this sentence: “After seven decades of national development and an expansion of the middle-class over a couple of decades, there are more poor people in Sri Lanka today than at independence.” The footnote was missing, so I thought I would check the facts.

The Government keeps track of poverty. According to the 2012-13 Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES), Sri Lanka’s poverty head count was 6.7%. I could not find the poverty headcount in 1948. But in 1990-91 it was 26.1%; in 1995-96 it was 28.8% (an increase over the previous survey). By 2002, it had decreased to 22.7%. So it appears things had considerably improved since the 1990s.

The HIES, a painstakingly conducted survey that included responses from 25,000 households, is a credible source of information. But the Department of Census and Statistics has taken some hits in the past few years. So I sought to find some additional evidence.

The food ratio is a good indication of poverty. The lower the ratio, the less poverty there is. As people get more money in their hands, they spend more on non-food items. In 2012-13 it was 37.8%, compared to 44.5% in 2002, 60.9 in 1990-91 and 65% in 1980-81. The ratio has been reversed from where it was in 1980-81. This is evidence of progress, of a reduction in poverty overall.

The difficulties of obtaining reliable data on income are well known. While the Government reports income data, it also painstakingly collects expenditure data which are considered to be more reliable. While Sri Lanka has a surprisingly high Gini coefficient of household income (0.48), the Gini for household expenditure is a little lower, at 0.40.

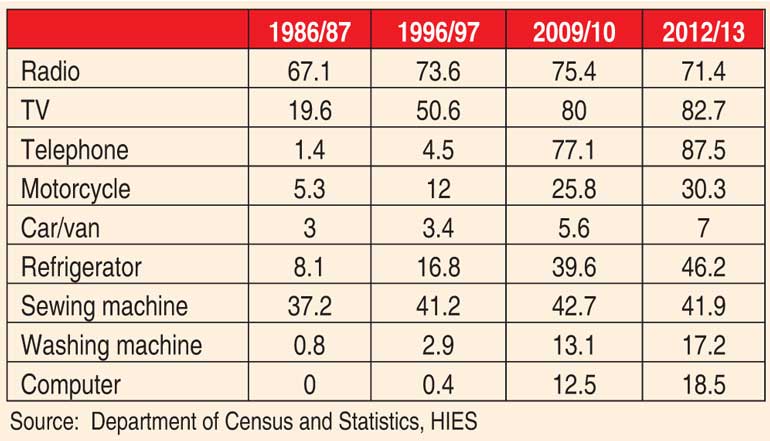

Another way of assessing poverty is to look at household assets. With some kind of phone available in 87.5% of households (up from 1.4% 25 years ago) and a television set in 82.7% (up from 19.6 percent in 1986-87), it is difficult to argue that dire and widespread poverty exists. It is noteworthy that now more households have refrigerators than sewing machines.

Life expectancy data is available from before Independence. It could be taken as an aggregate indicator of wellbeing.

People in poverty are unlikely to live longer than those less poor. In 1945-47, just before independence, the average life expectancy of a male Sri Lankan was 46.8 years; that of a female was 44.7. In 2010 average life expectancy of a male was 71.7 years. Females could expect to live six more years, having an average life expectancy of 77.9 years.

So it appears that the claim that poverty has increased since independence has little support. I have seen pictures taken of children with Kwashiorkor and Marasmus in Sri Lanka. But that was from the 1970-77 period of state socialism. There may have been an increase in poverty during that period, but things have improved much since then.

Sri Lanka could have done way better, given its endowments. But it has not worsened poverty, at least in the past 25 years. And things are much better than at independence.