Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Saturday, 4 February 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Independence Day marks the freeing of our country of the shackles of the colonisers. Our country won her freedom through the sweat of our predecessors who united in driving away the occupiers.

As a Sri Lankan, I love my country and feel that I belong here and nowhere else. As I join my fellow sisters and brothers in celebrating our independence, I long, more than ever, that our Motherland would be blessed with a vibrant society with people of different ethnicities and religions coexisting peacefully.

Born to a traditional Muslim family in a remote village in the Kandy District, I had the good fortune of studying at the “best school of all”, a Church Missionary Society school where we did not really care to what religion or ethnicity our friends belonged to. Religion was confined to our homes and all of us in school ate off the same plate and cherished our brotherhood; we broke up for our lessons on religion and returned, leaving what we had learned to be practiced in our private lives.

We entered the playing fields, and did not know the difference between Perera, Nayagam, Ahamed or Jurianz. We were comfortable in church or at the mosque, wherever we gathered to celebrate our differences. We need to wonder how we did it, when we think of how we live as adults today.

The thought of our 69th Independence Day brings back memories of my childhood, school, teachers, friends, and colleagues. It also reminds me of how distant we have grown on ethnic and religious lines, each of us believing we are superior, and growing intolerant of the other.

We are all guilty of not following the true teachings of our respective faiths, led blindly by the loudest religious and political leaders who are intent on realising their personal agenda. We have forgotten and fail to hear, and let the most vociferous rants sweep over the love, understanding, respect, and human values that our faiths teach us.

The divisions, which have been created, is a glass wall that has separated us, and it needs to be broken down. A wall as delicate as glass could shatter the hopes and dreams of a nation. It should be the easiest material to break, but needs to done with extreme care, without injuring or hurting anyone.

Where do we start?

Where do we start? We’re told that any change should first start from within. As a Muslim, I see that the private practice of our faith has been dragged to the public space. The company we keep, our dress, our mannerisms, our interests, and even the terms we use in our everyday speech measure our religiosity – all of these have become public markers of being ‘a good Muslim’. This has made us Muslims look ‘different’, different from the Muslim community that lived and interacted as Sri Lankans some decades ago.

I also see changes in religious and cultural consciousness along the same lines in other religious and ethnic communities living in Sri Lanka. All of us need to revert if we are to celebrate our differences and independence while standing united. Let’s keep our practice of religion as a private affair. We can certainly practice our faith without compromising on religious teaching and still be a proud Sri Lankan. Didn’t our parents and grandparents live that way?

The British who ruled us through their strategy of ‘divide and rule’ implanted racism and segregation amongst Sri Lankans. They made sure that the majority Sinhalese were kept ‘under control’ by bringing the Tamil community into administrative services, and encouraged the Muslims, who were traders, to continue in commerce.

The Sinhala Buddhists continued to be peasant farmers, deprived of their basic rights, necessities, education, and freedom. This gave rise to Buddhist revivalists like Anagarika Dharmapala to incite hate not just against the white colonialists but also towards the Muslim and Tamil population. Yet, since the greater enemy was the coloniser, there was unity amongst the political leaders of all communities to fight the common enemy.

This was rewarded by our blessed independence on 4 February 1948, where our great leaders accepted the challenge of marching forward as Sri Lankans together. Regretfully, in less than a decade S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike introduced racist and ethnic politics to Sri Lanka, with the Sinhala Only slogan. His assassination by a Buddhist monk put paid to the Bandaranaike-inspired racism.

The governments that followed attempted to bridge the gap that was planted by the colonial masters and Bandaranaike to divide and rule. More Sinhalese were absorbed into State service, educational opportunities were made available, competition was encouraged in business, and a semblance of justice was beginning to take its place. The minority communities saw these sudden changes as discrimination against them. State sector employment had more competition, business monopoly was challenged, and access to education for a larger population threatened the dominance of the elite.

Discrimination and increasing disparity

Sadly, discrimination also seeped in, and increasing disparity led to the ethnic conflict resulting in a 30-year brutal war which cost over 300,000 Sri Lankan lives, trillions of rupees to the nation and left behind a completely divided citizenry.

The military victory of the ethnic war in Nandikadal in May 2009 brought about euphoria amongst the majority Buddhist community leading to a ‘victor takes it all’ attitude. Further, the extremist Buddhists who assumed that they had finished off the Tamils now began targeting other minorities, particularly the Muslim community.

Over 650 incidents of violence, hate and intimidation have been recorded against the Muslims since 2013. The evangelical Christians too have recorded similar numbers. Commercial interests played a major role in this destabilisation process. Mosques, homes, Churches and businesses were targeted, thereby creating fear amongst the religious minority population.

President Mahinda Rajapaksa who claims to have united the nation when he won the ethnic war with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) failed to reconcile the divided nation even though all communities gave him a record mandate for his second term as President. A great opportunity wasted! He also manipulated the head count in Parliament by welcoming crossovers from the United National Party in Opposition with perks and privileges hereto unknown in Sri Lankan politics. This also gave him a two-thirds majority, which encouraged him to change the Constitution and attempt a third term at the presidency.

The coalition that came together to fight the Rajapaksa nepotism, corruption, racism, violence, and misrule brought about a Government that promised ‘Good Governance’. Two years on, the promised good governance, recovery of the stolen loot, investigations into the murders of Lasantha Wickremetunge, Prageeth Ekneligoda and rugby player Wasim Thajudeen seem only a mirage. Sri Lankans have once more become disillusioned by politics in Sri Lanka. This needs to be changed, and this can certainly be changed if we all resolve to do so.

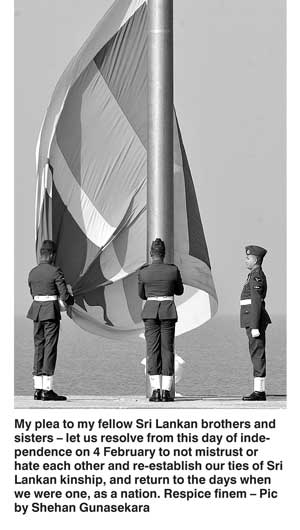

My plea to my fellow Sri Lankan brothers and sisters – let us resolve from this day of independence on 4 February to not mistrust or hate each other and re-establish our ties of Sri Lankan kinship, and return to the days when we were one, as a nation. Respice finem.