Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 18 July 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sharing production with the rest of the world

Sharing production with the rest of the world

The Sri Lankan-born economist of international repute and Australian National University Don, Prema-chandra Athukorala, offered a new economic policy strategy for Sri Lanka recently. He did so in a series of presentations made before a number of select audiences starting from the Institute of Policy Studies or IPS, Colombo a few months ago.

The Sri Lankan-born economist of international repute and Australian National University Don, Prema-chandra Athukorala, offered a new economic policy strategy for Sri Lanka recently. He did so in a series of presentations made before a number of select audiences starting from the Institute of Policy Studies or IPS, Colombo a few months ago.

In his presentation at IPS, he offered the choice to Sri Lanka: join the global production sharing chain or eternally remain as a lower middle income country (available at https://youtu.be/8ABAcDMoOvk).

Production sharing is a term coined by management guru Peter Drucker to describe a situation where components of a final product are being supplied by a large number of manufacturers.

What is known as production sharing today is a hybrid of the already known economic policy strategy – regional or global value chain. However, according to Athukorala, values can be created by enhancing the value added of the same product.

For instance, value added in cut flowers can be increased by undertaking the packing part of cut flowers within the country before being exported. Thus, the country in question joins the value chain of the same product.

Profits to be earned through massive scales of production

Production sharing, on the other hand, involves producing and supplying different components of a single product. For instance, Toyota cars are manufactured in Japan; but the parts for same are supplied by a variety of suppliers who have manufacturing facilities in different countries.

Production sharing, on the other hand, involves producing and supplying different components of a single product. For instance, Toyota cars are manufactured in Japan; but the parts for same are supplied by a variety of suppliers who have manufacturing facilities in different countries.

In the case of Toyota, air bags are manufactured and supplied, noted Athukorala, by a factory in Sri Lanka. That factory is, therefore, sharing the production of Toyotas with the original Japan based company. The profits to be earned from a single part may not be that much; but, when you produce for a massive global operation, it will come to billions of dollars.

Apple products are best example of global production sharing

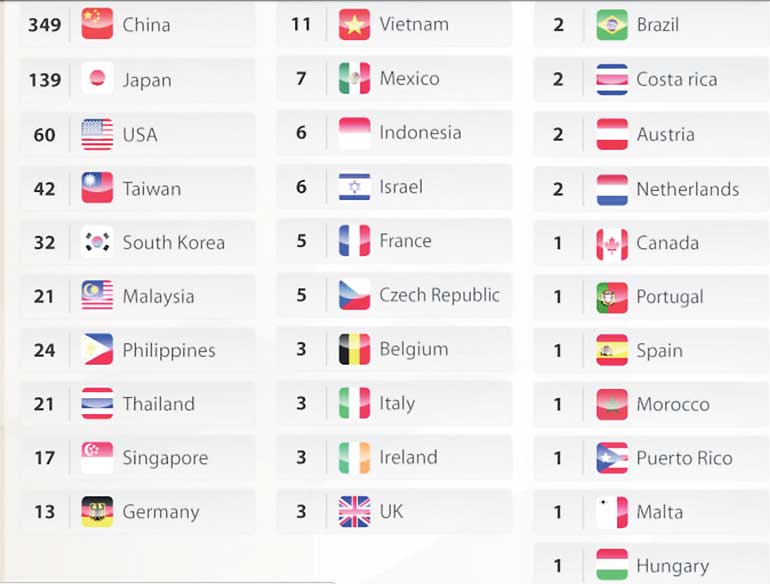

The best example for production sharing comes from Apple products. Apple products are designed either in the US or Israel. But once they are found to be commercially viable, they are manufactured in a factory in China called Foxx Con, a facility owned by a Taiwanese firm. For instance, components of the iPhone 6, as figure 1 shows, come from 815 production facilities in 31 countries (available at: http://betanews.com/2014/09/23/the-global-supply-chain-behind-the-iphone-6/).

The long list covers almost the whole globe, countries in Asia, Europe and North America. The countries involved are not all rich countries.

Components of iPhones come from both rich and emerging economies

In the list of countries supplying components for iPhone 6 are emerging nations like Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, Costa Rica, Puerto Rico, Morocco, Malta and Brazil. Thus, the iPhone is not a single country product but a global product enabling different nations to enjoy the fruits of that global production.

In the list of countries supplying components for iPhone 6 are emerging nations like Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, Costa Rica, Puerto Rico, Morocco, Malta and Brazil. Thus, the iPhone is not a single country product but a global product enabling different nations to enjoy the fruits of that global production.

Since more than 1.5 million people are employed in those facilities throughout the globe, the fruits of iPhone are shared by a large number of workers in both the rich and emerging countries. Hence, the globalisation of production through production sharing has been a real socialist move rather than a mere capitalist move.

The breakdown of the final market price of an iPhone 6 into different countries has revealed that each country gains only a very small value. For instance, the value addition in China, the country in which it is finally assembled, has been about $ 10 per phone. Yet each country makes a huge income for itself by basing its income on the massive international market for the product.

Production through global production networks

This production arrangement is commonly known as ‘supply chain’. But it denotes a wrong meaning because it connotes that the Apple buys those intricate and complex components off the shelf in the market.

In a sophisticated product like an iPhone, that cannot be done because the brand name holder has to ensure the quality of the product he supplies to the global market. Thus, according to Athukorala, they happen in prearranged contractual relationships known as ‘global production networks’.

These networks and their associated global production sharing chains cover both manufacturing and trade in services; in both cases, the brand name holder has to ensure quality in manufacturing, distributing, marketing and after-sale services.

Supplier responsibility programs are a must

Hence it is essential that the brand name holder comes up with a ‘supplier responsibility program’ to bind him to the global best practices of labour laws, individual country commercial practices, conventions and laws and technical quality specifications and requirements.

In the case of Apple, it involves continuous audit of the supplier unit over the compliance of the responsibility, tracking of labour practices and training of workers on labour rights and self-improvement practices. Thus, of the total global workforce of the Apple, 1.5 million workers have received training on labour rights and 280,000 on self-improvement since 2012. These are costs and additional responsibilities for the global final suppliers.

Agreed prices are not transfer pricing schemes

When goods are supplied through global production networks which are arranged for specific purposes, pricing becomes a problem. That is because they are not open market prices but those agreed upon with the supplier after deliberate contractual arrangements.

Since such prices are normally lower than the open market prices, the tax authorities might suspect that there is some form of ‘transfer pricing’ that enables the profits to be earned in the domestic economy to be transferred to a foreign destination.

Suspecting transfer pricing, the tax authorities might insist on paying a higher tax on the basis of the recalculated high profits based on the perceived earnings of the local company. Athukorala says that tax authorities should exercise care and caution in such cases to avoid the destruction of the whole industry through high taxation. Since producers have thin margins and global production networks are highly competitive, such short-sighted tax treatment of network participation will be fatal to local industries.

Manufacturing has the lowest value addition

But there is a caveat in promoting global production networks since the underlying value addition in the stage of actual production is lower than the normal case. One reason is that a particular manufacturer is supplying a small part of the full product and that small part may not be very expensive. Another reason is there are so many suppliers connected to a given brand name holder and the final value is distributed among all of them.

Consider the case of iPhone 6 where there have been 815 global manufacturers who are to share its final value. Hence, the manufacturers of components have to depend on the volume of supply to make big profits for themselves. The counties concerned will have to have a large number of such components produced and supplied to the global production networks.

In contrast, in the previous cases, the same brand name holder had under his control the supply of all the components of his final product and he got himself involved in both sales and after-sale services as well. Hence, the entire value addition got accumulated to the brand name holder. But in the current case, the value addition at each stage is shared by many manufacturers throughout the globe.

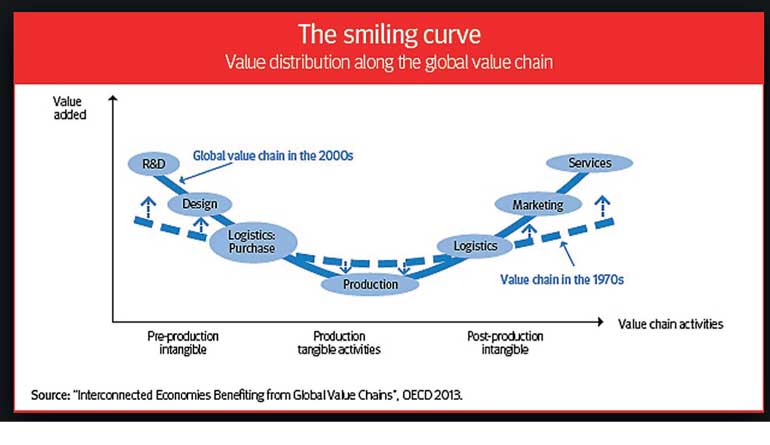

The Smile Curve

The comparison of the previous case with the modern model with respect to the value addition at each stage has given rise to the famous Smile Curve, invented by Stan Shih, the founder of ACER computers (available at http://www.uniba.it/ricerca/dipartimenti/dse/e.g.i/egi2014-papers/ito).

In the old value addition system that prevailed in 1960s in 1960s and 1970s where the whole of the work relating to the manufacture and supply of a product to consumers was undertaken by the brand name holder himself, there was more or less and equal value addition in every stage.

As reported by Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development or OECD and shown in figure 2, the Smile Curve pertaining to 1970s is a relatively flattened out U-shaped curve. However, in the modern Global Production Network system, it is a deep-bottomed U-shaped curve. What it means is value addition is high with respect to research and development and design but gradually falls when further processing of the product is undertaken.

In this system, it is the lowest when the product is actually manufactured; but it starts moving up once again with respect to marketing, sales and after sales services are undertaken.

Policy choices arising out of the Smile Curve

The Smile Curve presents several important policy options for emerging countries that wish to join the modern Global Production Network systems. First, there is a choice between high value addition and low value addition.

If a country desires to go for high value addition, it has to necessarily choose research and development stages in the pre-production stage or marketing and sales, in the post-production stage. But both are less labour intensive and based on high creative and inventive knowledge. A country cannot harp on these production stages unless it has already invested in an advanced science and technology foundation.

Cannot swim upstream without a science and technology base

Second, as a result, it is not a short-term option for an emerging nation like Sri Lanka whose science and technology foundation is at a very poor state. Countries like Israel, Ireland, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan are already swimming upstream well ahead of others in this respect. Then, there are second tier countries like India, Malaysia and Thailand in this region which are now picking up those front-swimmers fast.

Sri Lanka has to jump the bandwagon onto Singapore or India if it is to harness benefits from the emerging production network model. One way is to get into comprehensive economic cooperation partnerships or CEPA or the special Economic and Technology Cooperation Agreement or ETCA to be signed with India.

Countries should start with labour-intensive manufacturing stage

Third, more labour intensive and less-knowledge based stage of production is the manufacturing part of a product. But it gives less value addition and if a firm or a country is to benefit out of the Global Production Networks, it is necessary to strategise on scale of operation rather than the component itself.

An example quoted by Athukorala was Thailand’s Hard Disk Drive or HDD industry. The components for HDD come from a dozen of other countries and their current market price ranges from $ 0.04 to $ 0.045 per gigabyte.

Hence, there is no prospect of making big profits by a manufacturer or high value addition by a country. Yet, Thailand has been the leading HDD supplier to the global market supplying about 180 to 190 million units per annum. On that high scale, it makes a sizable addition to export earnings and GDP.

Yet, with changes in technology from server based data storage to extra-server based or cloud based data storage technologies, HDDs are increasingly being replaced by Solid State Drives or SSDs or Flash Solid State Drives or FSSDs. Hence, the future of the HDD industry is at risk today but the country is now making rapid progress in transforming the industry from HDDs to SSDs or FSSDs.

What this means is that the acquisition of adaptation to the latest technology is a must for any emerging economy desirous of benefitting from the new global production network model.

Sri Lanka’s exports are not performing well

Sri Lanka’s exports have increased in US dollar terms over the past decade. Yet, their performance in terms of GDP or global growth in exports or performance by peer countries has not been that impressive.

The share of exports in GDP fell from 27% in 2005 to less than 15% by 2015. Its share in global exports too fell from 0.08% in 2000 to 0.057% by 2014. It marginally increased to 0.06% in 2015 not because Sri Lanka did better but because global exports did worse in that year with an overall decline of 13%. However, the trend is clear: Sri Lanka is not doing well with respect to the growth in global exports.

When Sri Lanka’s exports increased only by less than two times between 2005 and 2015, the exports of Bangladesh, a peer country, increased slightly more than four times during that period. Bangladesh was able to do so by increasing mainly its garment and textile exports. Sri Lanka could not maintain the same tempo in garment and textile exports because of its inability to compete with that low-wage neighbour to the North.

The small fish can swim safely in the big pond with access to technology

This trend portends the challenges ahead of Sri Lanka when it has to beat the middle income country trap in a few years’ time. The plan of the current Government is to make Sri Lanka a rich country by 2030. How can it attain that objective if it cannot even rise above the middle income country status?

Being a small economy, Sri Lanka’s wealth and prosperity have to be created by producing to a bigger market than the limited market it has domestically. Sri Lanka is a ‘small fish in a big pond’ with scary waters all around. But with proper technology, as Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan did in 1970s and 1980s, it can swim in those scary waters safely.

Joining the Global Production Network is a must

The way to do so now is to graduate from simple technology producer to a complex technology producer. There again, given the constraints for developing technology in-house for gaining capacity for becoming a complex technology product producer, the way out for Sri Lanka is to follow the strategy suggested by Athukorala.

That is to become a partner of global production sharing rather than becoming an exporter of a complete final good to the global markets. The new foreign direct investment strategy to be followed by Sri Lanka should take cognition of this factor.

(W.A Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])