Sunday Dec 14, 2025

Sunday Dec 14, 2025

Wednesday, 16 March 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

An oxymoron is a situation where seemingly contradictory elements are brought together. In the present case the contradictory elements are innovation and public universities. I have been hearing so much about our public universities as leaders of innovation that I feel we need to keep harping about the quality of our universities and why they need to innovate before they help others.

An oxymoron is a situation where seemingly contradictory elements are brought together. In the present case the contradictory elements are innovation and public universities. I have been hearing so much about our public universities as leaders of innovation that I feel we need to keep harping about the quality of our universities and why they need to innovate before they help others.

The impetus for this column is an initiative by GIZ to build university-industry partnerships under the broader theme of developing the SME sector in Sri Lanka. Two seminars have been held to date. I attended both. The content was educational about innovation in SMEs, but I confess I was sceptical about the role of public universities.

The second seminar was more useful because there was participation by CINEC, a private higher education institution and Brandix, a major export-oriented company. While university representatives talked about government interventions to build functioning eco-systems and so on, the private sector came up with more practical approaches.

The Brandix representative noted how a program co-organised with MIT, USA, could not be carried out as planned because our universities did not have a synchronised academic calendar which would give extended period of off-days or vacation time for our students at a designated time of the year.

Captain Ajit Pieris of CINEC pointed out that the priority of our universities is to turn out innovative graduate and leave it to the graduates to bring innovation to the SME sector. Comments from the audience was to the effect that our universities should be innovators themselves.

Yes, public universities need to innovate first

Universities are conservative institutions. European and US universities have survived over five centuries by adapting while preserving their structures more or less. Roger L. Geiger identifies 10 stages of adaptation demonstrated by universities over the five centuries. We will look at the more recent history where the trendsetter has been the USA.

Universities are conservative institutions. European and US universities have survived over five centuries by adapting while preserving their structures more or less. Roger L. Geiger identifies 10 stages of adaptation demonstrated by universities over the five centuries. We will look at the more recent history where the trendsetter has been the USA.

The 1900 to 1945 period was the ‘Growth Period’ fuelled by increasing admission of war veterans to the universities. The 1945 to 1970 is called the ‘Academic Revolution’ with universities being major players in the technological pursuits of the Cold War.

The 1970s-1980s is called the ‘Dismal Period’ marked by cutbacks, and 1990s and beyond is called ‘Entrepreneurial Period’ where entrepreneurship is incorporated into teaching and learning and the universities diversifying their funding sources through entrepreneurial activities. Public universities in Sri Lanka have experienced an academic revolution of sorts and a dismal period, but they have not responded with entrepreneurship.

Present status

Public sector is the last resort for higher education for the average family in Sri Lanka. Private higher education is growing, but it will not make a dent in the demand for public higher education by these families. Besides being free-of-charge, the public higher education sphere offers a comfort zone for the average Sri Lankan youth. The elite-average divide in Sri Lanka is a Grand Canyon of disparity with a globally-connected English speaking elite on one side and unconnected Swabhasha majority on the other side.

During the decades from 1940 to ’60, the public universities served as places where youth from rural Sri Lanka gaining access to the university were assured of an education that opened doors to the world. Overtime, public universities have receded from this bridging role, and today they seem settled on the unconnected side of the cultural Grand Canyon in Sri Lanka. Reforms for the better seem impossible.

The incentive system in higher education is such that there is no compulsion for change. A chance for a free-of-charge opportunity for a degree will continue to bring students to the doorsteps of the public universities – i.e. a continuous supply. Governments will continue take to easy way out and use public funds to find employment for the graduates – i.e. an artificial demand. The faculty and administrators are absolved from all responsibility. Essentially, our university system seems to be in a state of equilibrium with little incentives for change.

External actors and the higher education iron triangle

The classic narrative that explains the non-occurrence of reforms is the “iron triangle.” (Gordon, 1981). Politicians, bureaucrats and constituencies (as opposed to consumers or citizens) find themselves locked into mutually reinforcing relationships that stymie reforms; even if one group wants to effect change, one of the other two or the other, or both will negate it. In another scenario, all three will corroborate, knowingly or unknowingly with each other to maintain the status quo.

The ‘Iron Triangle’ concept has been applied to education both in its original sense (West, et al., 2012) and from a management perspective (Daniel et al., 2009). Applying the concept in its original sense to education in Sri Lanka, the faculty, students and the politicians form the three corners of a dysfunctional triangle in higher education.

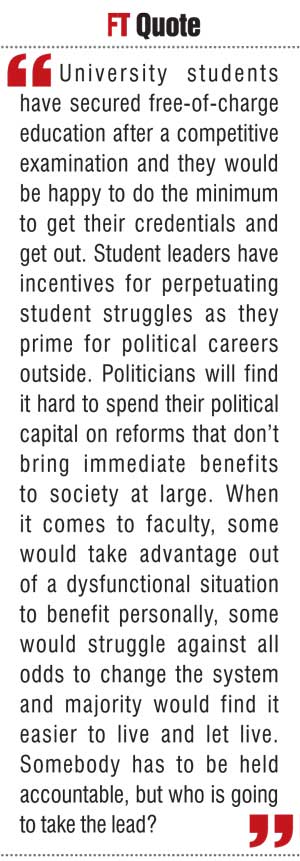

University students have secured free-of-charge education after a competitive examination and they would be happy to do the minimum to get their credentials and get out. Student leaders have incentives for perpetuating student struggles as they prime for political careers outside. Politicians will find it hard to spend their political capital on reforms that don’t bring immediate benefits to society at large. When it comes to faculty, some would take advantage out of a dysfunctional situation to benefit personally, some would struggle against all odds to change the system and majority would find it easier to live and let live.

Somebody has to be held accountable, but who is going to take the lead?

Role of the University Grants Commission (UGC)

UGC was established in 1972 in the middle of an inward-looking era in our economy. Its original function as its name implies was to receive and distribute grants from the government. At that time the focus was largely on preparing graduates for public service and public enterprises.

Today when universities in the rest of the world are looking at an entrepreneurial shift, the University Grants commission is stuck in its archaic definition of its role. They seem to be simply changing the deck chairs for the narrow and ill-conceived objective of increasing intake to the public universities.

Arthur Stinchcombe in his 1990 book ‘Information and Organisations’ used the title ‘Managers who do not know what their workers are doing’ for his chapter on universities. This is something university authorities should remember as they skilfully fend off political interferences. But UGC should use the leeway so obtained to bring about meaningful changes to the system. For example, The Universities Act gives UGC the authority to shape policy not only for public institutions but for the whole higher education sector, if they so desire. The bold leadership required is sadly missing.

UGC and the World Bank

The World Bank has been providing much-needed funds for the development of the higher education sector since 2003. If the UGC and the World Bank work together, UGC taking the lead in policy formulation, much can be achieved. Unfortunately, there is no policy capacity at the UGC or the MOHE and the lead education specialist for the World Bank has been driving formulation and implementation from 2003 or so to date. A priority for the World Bank should have been to develop local policy capacity for the sector, but they have not.

The first grant aimed at Improving Relevance and Quality of Undergraduate Education (IRQUE) was $ 55 million in value and was spent between 2003 and 2007. The major accomplishments as listed in the project report include establishment of IT and English programs; Higher Education Management Information System (HEMIS) created and used; Labour Market Observatory (LMO) established at the Ministry of Labour; Board for quality assurance (BQA) constituted, operational and maintained and the Quality Assurance and Accreditation Council (QAAC) as a separate division of the UGC with effect from March 2010; 4,148 personnel trained national planning, monitoring and evaluation systems; and 219 personnel trained in institution’s planning, financial, HR, academic and physical assets management.

The second project which is named the Higher Education for the Twenty-First Century (HETC) listed as its achievements as of December 2015 that 71%-76% of students are participating in and benefiting from the English language and IT skills certification programs; QA cycle implemented 100% for universities; The Sri Lanka Qualification Framework operational for the full higher education sector; 60% of the chosen academic staff have completed their master’s programs ; and 100% of the University Development Grants disbursed. Apart from achievements in IT and English certification and upping the number of faculty with post-graduate qualifications, the question we would ask from the outside is ‘so what’?

Further support of the World Bank is essential for the future of the higher education sector, but, one would hope that the Bank would move away from the practice of starting up unsustainable information systems or other initiatives from inside and focus on systems and tools for breaking through the ‘iron triangle’ of dysfunction in the public higher education sector in Sri Lanka. Some of the proposed initiatives from the election manifesto of the present Government could be a starting point.