Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Tuesday, 17 May 2016 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka is blessed with high rainfall, especially in and around the central mountain regions. The heavy rainfall and sloping nature of the lands resulted in number of small and large streams carrying water year around, allowing for a number of reservoirs, enabling power generation to fulfil a substantial part of the country’s power requirement. While the Government carries out large power generation projects, projects less than 10MW capacity have been given to the private sector. Local companies investigate possible locations, get acceptance, construct and install power plants and produced power is sold to the CEB.

Hydro structure

Hydro structure

History

During the colonial era, tea and rubber factories in the hill-country had over 400 small hydropower generation units that supplied the bulk of their electrical power needs. In the 1970s, with the commissioning of the power stations around Laxapana, the CEB encouraged the factories to close down these small generation units. During the 1980s, Premasiri Sumanasekara who introduced locally made cheap school mini-labs under Vidya Silpa, re-commissioned some of these abandoned power plants. With the knowledge and experience gained, he was responsible for the first private hydropower generation unit at Dick-Oya with a capacity of 1 MW and supplied power to the CEB.

Power plan

According to the 2015 report on “Sri Lanka Energy Sector Development Plan for a Knowledge-based Economy, 2015-2025”, the country’s total power generation capacity amounts to 4,050MW consisting of 900MW from coal, 1,335 from oil burning thermal, 1,375 from hydropower and 442 from non-conventional sources as wind, mini-hydro, biomass and solar power.

Presently, over 15 private sector companies are engaged in small hydropower projects and supply 293MW of power generated in 150 power plants to the national grid, which amounts to 17.5% of hydropower generation in the country. The same report envisages utilisation of all possible locations contributing 873MW of power by the year 2025.

Structure of a small power plant

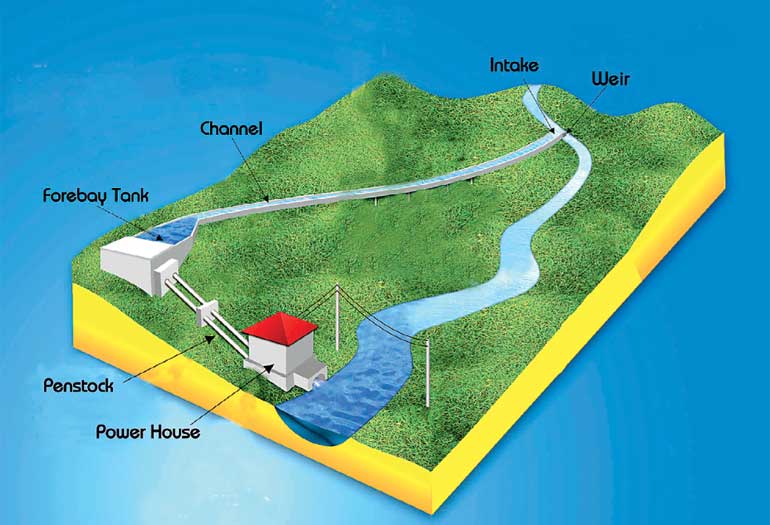

The power of water flowing down a stream or a river can be used for the generation of hydroelectricity. The quantum of power generated would depend on the water quantity and the height difference between the collection point and the generator location referred to as head. Thus, streams in heavy rainfall regions with high ground level variations over short distances (steep slopes) are suited for power plants.

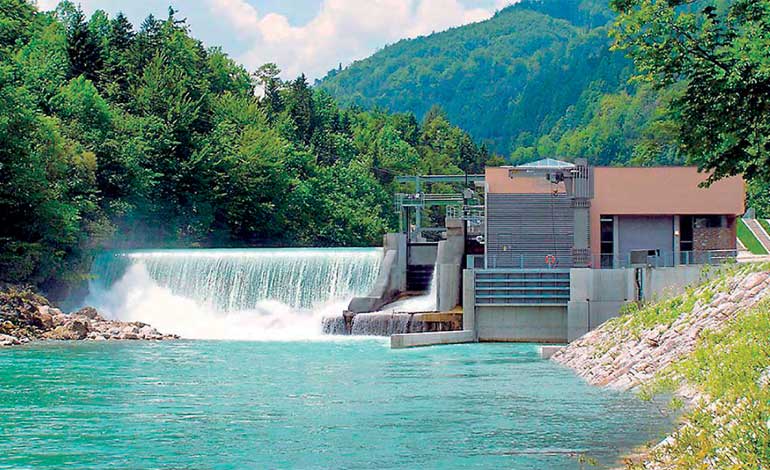

The water in the stream is diverted by a small dam; generally referred to as weir, into an open channel (the ‘intake’). High dams store water for major power projects, but in mini-hydros storage is disallowed. The dam is incorporated with a permanently open outlet, allowing a predetermined minimum water flow to fulfil needs of down-stream users for domestic and agricultural, for survival of fish living in the stream and drinking water requirements of animals. The weir also incorporates a spillway to discharge excess water during heavy rains.

The weir would divert the water to a concrete channel and will enter the desilting tank (a settling basin), that would settle sand and mud brought by the stream. The channel follows the contour of the hillside to preserve the elevation of diverted water. At the end of the channel, water enters a tank known as the ‘forebay’. The forebay tank forms the connection between the channel and the penstock. The forebay tank allows the last sand particles to settle down before the water enters the penstock. A sluice arrangement allows to close the entrance to the penstock and divert water to a spillway, bypassing turbines. The penstock pipes are generally steel, conveys water under pressure from the forebay tank to the turbine, which generates power. After power generation, water is led to tail-race back into the stream.

Approval of a small hydro project

Small hydro projects are implemented by private developers. Getting acceptance and approval of a small hydropower project involves extensive investigations and going through masses of red tape as summarised below.

When a developer discovers a possible location for a hydropower plant, he would investigate the viability and submit an application to Sustainable Energy Authority (SEA), which would issue a provisional approval (PA) for development. With the PA, the developer will apply for a letter of intent from the CEB and environmental approval from the Central Environmental Authority (CEA).

The CEA would refer the application to another authority acting as Project Approving Agency (PAA). The PAA sets in scoping meetings and government agencies from which the developer needs to get approval for the project, which would include no objections from the Grama Sevaka and Divisional Secretary, who would call public meetings. The PAA also will issue terms of reference (TOR) for an initial environmental examination report (IEER).

The developer submits the IEER to the PAA along with other approvals to be evaluated by the technical evaluation committee (TEC) appointed by the PAA. If accepted, environmental clearance is issued to the CEA for the Energy Permit (EP).

With the receipt of the EP, the developer is permitted to commence physical construction at the proposed site. The developer would submit an application from the Public Utilities Commission of Sri Lanka (PUC) for an Energy License and apply for signing a Power Purchase Agreement with the CEB.

Developing a small hydro project

While the technical feasibility evaluation of a project would be straightforward, the environmental aspects could be extremely complicated. Most feasible projects, located in steep mountainous terrains, providing high head over a short distance, are difficult to access and sometimes the stream may have cascades or minor waterfalls. These regions are sparsely populated, but surrounding regions would be populated, as only very few areas in the country are uninhabited.

The weir and intake are located on the stream, the channel conveying water could be over a kilometre in length, the penstock is located on a steep slope ending at the power house by the stream. The construction of the weir, channel and especially the power house would require rock excavation and blasting. Most structure locations are inaccessible and the developer needs to build roads or improve existing footpaths to allow construction vehicles and equipment. Power generators are very heavy and after the construction, operation of the plant needs regular access, thus proper roads are required.

Environmental concerns

The acquisition of lands for locating the structures as well as access roads, and modifications carried out to the existing stream and neighbouring grounds that has been receiving heavy criticism from environmental groups. Presently, the country having developed over 150 projects, developers are experienced and are extremely concerned of environmental issues during the design and the construction phases. The acquisition of lands from private individuals would be mostly for the widening and improvement of access roads and sometimes bridges, which are negotiated and paid for by the developer, would facilitate villagers as well.

But some extent of damage mostly temporally, cannot be avoided to stream bed and immediate surroundings during the construction. The highest land requirement would be for the channel carrying water from the weir to power plant, requires around 5m width and could be over a kilometre long. The total land requirement for a small hydro project would be around five acres.

The environmental approval process requires no objections from the Grama Sevaka and the Divisional Secretary who would call public meetings to discuss the project’s impact with the villagers.

Objections by environmentalists

Although a project may not be objected by the majority of villagers, it could be subjected to severe criticism from environmental groups along with some villagers. Most of their criticisms would be based on the following;

1. The project location and the stream is a paradise for fresh water fish, with a number of species discovered in this unique habitat,  and the indigenous fish would be endangered by the proposed project.

and the indigenous fish would be endangered by the proposed project.

2. Change of water flow in the stream is a death sentence to many species living in the micro-habitat, not only fish, other amphibians and fresh water crabs are affected.

3. The biodiversity rich region hosting aquatic orchids, found in spray zones of the waterfall, would be destroyed when the flow in the waterfall gets reduced.

4. The cascades and waterfalls enjoyed by the locals and visitors would disappear due to diversion of the stream.

5. Damaging the buffer zone of the Sinharaja World Heritage rainforest complex.

6. Possibility of negligence of the developer could cause massive environmental destruction, affecting the stream, rainforest, soil and endemic fish in the region.

7. The dam would obstruct fish moving upstream for egg-laying.

8. In one statement, the environmentalists claimed the destruction of a 6.5km-stretch of stream.

9. In another, they claimed the power generation would change the pH value (acidity) of water.

Reality

1. Most of our streams in the wet zone are alive with small fish, but power generators are forced to install a permanent opening in the weir, which cannot be closed, would allow agreed minimum amount of water flow for fish as well as users downstream from the weir. The entire water quantity would be discharged back to the stream after power generation. The reduction of water flow is only between the weir and the power house.

2. The aquatic orchids, found in spray zones of the waterfall are only imagination. However, wild orchids do exist in Sinharaja and the wet zone. In Matugama, Agalawatta and Kalutara during Vesak/Poson period, villages bring loads of Vesak orchids for sale.

3. It is common for environmentalists to refer to most regions in the hill-country as Sinharaja World Heritage buffer zones.

4. A large number of cascades and minor waterfalls exist in the proposed projects due to steep change of elevation in streams. Any waterfall in the list of waterfalls would not be allowed for development. In cascades, the minimum stipulated flow will not allow the cascade to disappear. The improvement of access roads by the developers would allow the region to be more accessible to visitors.

5. Negligence on the part of developer’s staff is a possibility, the developers should take action to prevent any accidents and if it does happen, the developer should be heavily fined.

6. Salmon moving upstream for egg-laying is common in cold Western countries, but similar local fish are unheard of.

7. The claim of destroying of 6.5km stretch of stream is unlikely. I have details of 34 power plants in the country, the maximum canal length is 3,928m, the minimum 174m and the average length amounts to 1,299m.

8. The change of pH or acidity levels in water gone through a generator is impossible as no chemicals are added during the generation process.

Location ownership of hydro projects

Analysis of 34 power plants indicating ownership of lands where power plants were built, as follows;

Forest 01

Forest and private 01

LRC 02

Plantations 07

State 02

State and private 12

Private 08

Temple 01

Above shows forest lands were used only in two out of 34 plants. Most were state and private properties; the projects in plantations were executed in collaboration with the plantation companies.

Destroying forests

Some claim mini-hydro projects destroy forests. A power project produces an average of 2.5MW of power and uses nearly five acres of land, mostly for the channel occupying a 5m wide stretch. Sri Lanka’s hydroelectricity generation is 1,375MW and the total power generation capacity (coal, diesel and hydro) amounts around 4,000MW. If this total power requirement was supplied by mini-hydro it would occupy 10,000 acres. Meanwhile, the Kotmale Oya reservoir alone occupies 5,750 acres, thus considering land usage, the mini-hydro requirement is negligible.

Projects challenged by protestors

Most actions by humans would harm the environment even in a minor manner, and even the meticulously planned and executed project would not satisfy every individual. Some others would be jealous, and minor differences among villagers flare up. Local politicians may feel they were not consulted or were not given sufficient prominence. These minor differences are used by so-called environmentalists, politicians and individuals to create protests. Unfortunately, for some environmentalists in the country, environmental concerns and protests are only for their income generation. They protest over flimsy incidents, with people holding placards lasting only half hour, until video clips are produced. Our TV channels too are prepared to broadcast video clips without investigating in depth. Some so-called environmentalists are being paid by NGOs overseas, and to get the next payment instalment they are expected to submit a progress report.

Benefits to the country

The mini-hydro organisations boast of their risk taking pioneering effect, with long-term profit concept, ability to adapt global know-how into local ventures and their efforts being recognized by the World Bank as the “best performing project” of its kind. Mini-hydros claim to have produced 902 GWh of electricity in 2013 and if the same was generated by coal, the country would have spent Rs. 19.2 billion and they have saved foreign exchange. They also claim if the power was generated by coal or oil, the environment damage due to emission gases would have been enormous.

Projects and the locals

Most mini-hydro projects are mostly located in difficult to access, mountainous regions with sparse population. While some projects improperly planned could harm the environment, but after decades of experience, most developers are concerned of environment and introduce measures to control and mitigate possible environmental and human problems. Improvement of access roads would help the villagers and construction activities will provide employment to villagers and the running project will employ some locals. All in all, the village will benefit by the project.

But human issues are more complicated. Petty differences among villagers and political issues could delay or cancel a project. This aspect is being manipulated by environmentalists and politicians to serve their own ends. The manipulated public protests and TV reporting scares government officials who are expected to approve the project with public consultation. Public officials who dislike being involved in controversies refuse to approve or delay approvals, placing the developer in a dilemma.

Balancing concerns

Small hydro projects developed by the private sector with no financial contribution from the Government have made a substantial contribution to the country. Their endeavour especially in a field of technology and the export drive need to be commended and is an example to others.

As envisaged by the “Energy Sector Development Plan” Sri Lanka needs to develop every possible source of hydroelectricity by 2025, which would prevent drain of foreign exchange. The local industry has matured to handle projects with environmental concerns while respecting interests of the local populace. Today, practically every possible location, numbering around 800, has been identified for mini-hydro generation, but the majority are not financially viable. The private developers are awaiting CEB acceptance to implement viable projects. But the CEB has a program and will the CEB be willing to accept more power producers beyond their program? The quicker implementation of all possible hydropower projects, mini or otherwise would benefit the country.

The approval process of projects includes in-built conditions addressing environmental concerns, and when agreed conditions are implemented, damage to the environment would be minimal. The government officers and environmentalists too need to look at projects in a more positive manner, but this should not be a licence to create havoc with the environment. Everyone from developers, government officials and environmentalists should work together for the development of the country and the benefit of local population.