Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Tuesday, 22 November 2016 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The recent Budget proposal that the ownership of tea would be restricted to 5,000 acres sure surprised the privatised tea industry of Sri Lanka. Though a privatised business of the industry generates only 35% of the total production of the country, it gave Sri Lanka the opportunity to practise a modern management technique and value chain development with some companies beating out global brands in the local market that indicate the talent base in the industry.

I would be failing in my duty if I didn›t say that it also revealed to policymakers that unless there was continuous monitoring of a leased asset of a country there could be ramifications given that the private sector’s objectives naturally would be profit-taking and ROI.

The tea industry is what gives the country its identity

The tea industry is what gives the country its identity

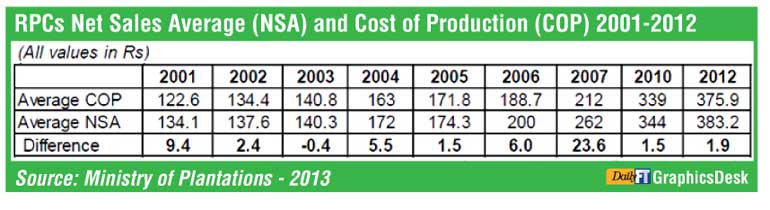

If we were to go back in time, we would see that the gap between the Cost of Production (COP) and Net Sales Average (NSA) was 9.4% in 2001. Over time, due to various issues, this difference has contracted to just 1.9%, which indicates the serious issue that the industry is up against purely from a survival perspective. This would have come to light if only there was some degree of periodic evaluation between the policymakers and private sector.

The above highlights the strategic decisions either of driving the efficiency of the supply chain or taking remedial measures like merging the demand chain with export companies so that business becomes viable. In fact in a previous Budget there were tax indentures offered to achieve this end but they did not materialise for some reason.

It’s important to track back the history of the RPCs. In the 1970s, large extents of plantation lands were acquired by the Sri Lankan  Government and came under the purview of State institutions such as the Janatha Estates Development Board (JEDB) and the Sri Lanka State Plantations Corporation (SLSPC) under the Land Reform Act No. 1 of 1972.

Government and came under the purview of State institutions such as the Janatha Estates Development Board (JEDB) and the Sri Lanka State Plantations Corporation (SLSPC) under the Land Reform Act No. 1 of 1972.

However, with the increasing inefficiency of the two corporations that were Government-owned the JEDB and SLSPC sought Government assistance to offset the mounting operational losses that had increased to almost Rs. 1.5 billion per annum for both corporations by 1992.

In the face of mounting financial losses suffered by the two corporations, the Government appointed a taskforce which recommended the entrustment of the management of the plantations to the private sector.

In view of this, the Government initiated the privatisation of the sector in 1992 which led the Sri Lankan tea industry to witness one of the most significant structural changes in the history of its industry. Incidentally the tea industry was the first to undergo the privatisation process in the country.

In 1992 when the State opted to privatise the management of State plantations, 23 Regional Plantation Companies (RPCs) were set up, of which 20 RPCs were leased out to 12 management companies during the period 1992/1993, resulting in the conversion of 461 estates managed by the JEDB and SLSPC to 20 RPCs under the Companies Act No. 17 of 1982.

In the administrative structure of the RPCs, 100% ownership was retained by the Government, while the respective RPCs were initially assigned lease-hold rights of between 12 and 29 estates for a period of 99 years for a nominal lease rental and thereafter adjusted the same to 53 years.

This was the birth of the new operating model of the corporate tea sector of Sri Lanka. With the new management architecture in place, it resulted in the best tea plantation managers being absorbed by private sector corporations during the post-privatisation period.

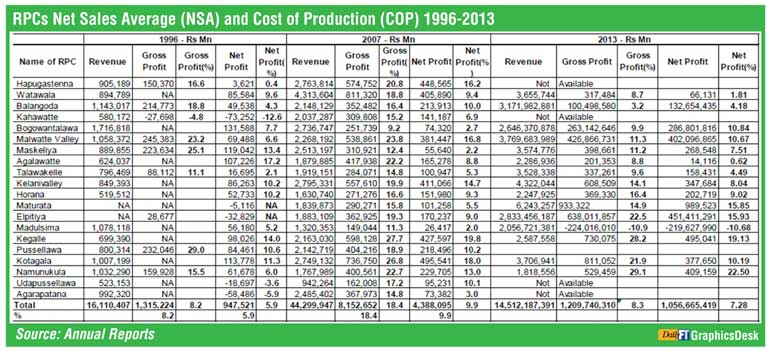

Let’s accept it that the RPCs turned the Rs. 1.5 billion loss-making venture toward profitability. In the financial year 2007/2008 the RPC recorded the best performance of a Rs. 14.9 billion net profit with the addition of modern techniques of management, which provided structure to the agriculture-driven colonial entity. But by 2013, we see that the hard work done by the private and public sectors was coming apart given the challenge from the supply chain area.

In 1996 when the privatisation agenda was in play, the gross profit was at 8.2% and net profit was 5.9% while with some strong decisions by the private sector and favourable global climate the GP was increased to a healthy 18.4% in 2007 and a net profit of 9.9 by 2007.

However, with available data we can see the challenging situation in 2013 with an 8.3% gross profit percentage and 7.2% net profit. In fact if one were to invest their money in a bank account the return would be better with a zero risk.

One key ramification of the above low profitability issue is the low investment in replanting just to keep the organisation alive. If we analyse the available data, it is reported that from the total extent of Old Seedling Tea (OST) in Sri Lanka, 75% belongs to the corporate sector and only 9% of this extent has bushes younger than 60 years of age while the rest is well over 60 years.

Hence it could be said that the senility of the tea bushes is one of the main reasons for the declining productivity and correspondingly lower production volumes that Sri Lanka has witnessed in the recent past.

A key remedial program that can be implemented is a robust replanting program in the RPCs. But with the current issue of COP converging on NSA, this remains a statement on paper that cannot be implemented practically.

One study by the Tea Research Institute states that the current volume of approximately 126 million kg output from the corporate tea sector will decline to 98 million kg of tea within the next five years as the tea in this sector is at a senile stage and yield is declining rapidly.

If one quantifies the loss to the country in volume terms, this will be around 28 million kg of tea per annum and in value it will be $ 92 million while in rupees it will be a colossal Rs. 9.9 billion. I guess these are the points that need to be taken into account when wage rates are to be increased but sadly these aspects are not even on the agenda.

The TRI has outlined a scheme for a replanting program to be implemented. The issue however is that for one hectare of tea to be planted costs almost Rs. 4 million which cannot be justified financially given the escalating COP and corresponding NSA value. This is why the replanting rate has been at a low ebb, according to some research reports.

The Tea Research Institute (TRI) stipulates that the replanting rate must be around 3% in a healthy agricultural practice system. But once again this has been an echo on paper as its financial viability is questionable. Especially with tourism conglomerates, renewable energy and maybe even education can be more attractive business ventures than investing in the tea sector.

Hence it is clear that unless some serious policy decisions are made based on market dynamics, Sri Lanka’s tea sector will be heading towards very rough waters. The 5,000-acre per company announcement sure shocked the industry given the liabilities the companies are challenged with but there was a study done at one time where it was proved that the outgrower model is probable strategy to follow.

We must keep in mind that the tea industry is the first privatised entity in Sri Lanka and it has been kept alive with some smart and sharp working models given that in the last 20 years amidst the war the industry held the country together.

Now that peace has returned along with a Government with an outside focus, the need of the hour is strong and structured decision-making in a balanced manner between the private and public sectors based on facts and data.