Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Thursday, 16 July 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is interesting to contemplate, as you are walking down the corridors of power without you yourself having any power, the ‘look and feel’ effect you encounter. You do not dare take the centre line and you use the path closest to a wall. If a door opens then you jump to the other side. You have no identity and the looks keep you down. It is an experience to experience.

However, if you have a scientific mind, which means that you observe, hypothesise and are keen to engage in experimentation, then you want to see results to validate what you were thinking and then you begin to understand that in some of these corridors of power you are witnessing ignorance in action.

That means that your hypothesis of proper functionality, what should be the natural time limits for action and results based on current technologies and service capabilities, are not exactly valid.

You begin to see that the natural cause and effect relationships can have indefinite time lags and you may have to provide additional information to questions fired back sequentially, which serves no purpose other than to provide an opportunity for delays.

The power of indifference when exercised within corridors of power is significant. I believe that is the difference between those who land on the moon and those who plan and take an inordinate amount of time over a water supply scheme of a few kilometers in length when people are dying due to a lack of clean water.

We always believe that the characteristic of indifference is not something to be improved on as an individual attribute – there are perhaps exceptions but they should be addressed in a later column.

This is certainly true of an organisation or institution for they cannot be indifferent to their goals and deliverables. Here we really would like to discuss an important area which for a long time we have shown nothing but indifference.

The world has moved on through multiple economic systems. We experienced the agriculture economy to start with. It was when humans started engaging in agriculture that we declared ourselves civilised human beings. We grew food and domesticated animals and in turn were rearing animals for food and work.

The agricultural economy evolved over a long period. The main attributes were land, labour and natural resources. Conflicts were quite common over natural resources. Then the manufacturing economy was ushered in. The presence of an industry made a decisive  impact on society.

impact on society.

Urbanisation and townships all became part of the new economic order. The relative importance shifted to capital, machinery and management. Dramatic changes to societies were observed as industry gained a foothold in economic planning.

Today it is all about knowledge-based economies. In this economic order science and technology, innovation and entrepreneurship are the dominant factors of economic production.

However, scanning all global economies we will not miss observing predominantly agricultural economies and we will continue to witness pockets of such practices. Until perhaps 3-D printing can print our menu for the day we will continue to support agriculture and we may not see a dominant switch to a different format of food production than what we have observed over the centuries.

However, industrialisation of the agriculture systems are with us as one witness with developed economies. Unlike a developing economy, the number of people engaged in agriculture as an occupation in a developed economy is a small fraction of the population.

When we continue to state that we are an agricultural economy perhaps we are not really doing ourselves justice. We appear to want to maintain the status quo and are perhaps demonstrating ignorance on how things have been changing.

Statements and subsequent decision-making based on erroneous thinking can really stymie progress. While paying homage to an agriculture economy we express vision statements as moving into knowledge economies and planning knowledge hub status.

Science and technology and innovation

Note two dominant factors in a knowledge economy - science and technology and innovation. We dream of a new economic order while being completely indifferent to its salient factors. This is where the story begins. We have been indifferent to the change around us. Some changes are certainly making us behave differently yet we do that more in a Pavlovian mechanism rather than from a piloting position with understanding.

The simple indicator is the role science and technology and innovation plays in our economy. As you do not much hear about these terms and also when you hear technology there is also the tonality of accusation towards it having had a corruptive influence on society. We fail to realise it is the deployment of some tools without understanding that is leading to this problem and technology per se should not be blamed for that.

For science and technology it is a lonely battle in the country. The talent that had been nurtured through a system of free education over a long period has simply disappeared elsewhere.

Many have amply demonstrated their prowess where the conditions are just right. The numbers coming into science are dwindling today as science is not the most preferred option for many as we hear commerce as the way forward for many.

This country perhaps boasts of the largest student body in accounting and marketing outside the United Kingdom when we take the enrolment of students in professional courses provided by a couple of United Kingdom-based organisations. What is worrying is not these numbers but the lack of balance that we are facing. We have far too many professionals who may be mostly counting losses.

When you hear some scientists who have returned to the country after postgraduate studies you hear the comment that they are here because of their parents, etc. and I wondered at one point if Sri Lankan scientists did not have parents whether Sri Lankan science would have been dead a long time ago.

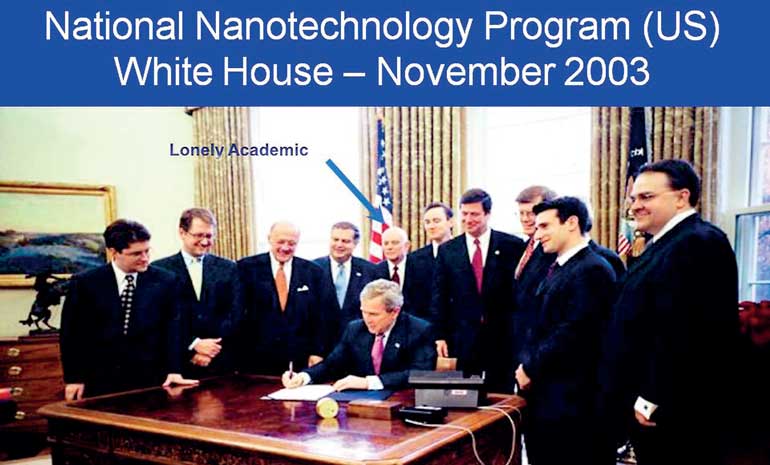

Other countries have seen these pitfalls too as science has been a profession which has lacked glamour though once a contribution emerges there are many willing users. It is nice to contemplate the picture of a Nobel laureate standing well behind US President Bush when he signed into law the US Government’s National Nanotechnology Initiative.

In some pictures that reached the public, they had to indicate the presence of the academic differently. To some extent we can take comfort that the scientist had to perform almost always against the odds but must have to be contend with the knowledge that what you do will matter to most.

The question one still has to ask is when at least some balance to this situation will be realised considering the enormous contribution to human progress is usually made by science.

We see many an issues in our country where the scientific approach and emphasis is missing.

Minamata response

Take the issue of CKDu (the chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology) which is affecting lives of thousands. For nearly 20 years the problem has been with us. Yet the focused approach and the use of tools of science have been limited and the ‘unknown’ factor is still present while the disease is taking a significant toll on the community.

When the Japanese faced the Minamata disease in 1950s they took it very seriously and with such intent the cause became known, environmental agencies were established to deal with all such issues, museums were established to tell the story so that future generations were spared of such horrors and also went to the extent of a global crusade against the responsible chemical.

Today the Minamata Convention has come into regulate mercury usage and Sri Lanka too signed onto the convention last year. There are many other examples of this nature that one can point out. Again we may not be a special basket case as you consider the comment of another Nobel Laureate.

Sherwood Rowland, who won a Nobel Prize for his research into the effects of chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) gases on the ozone layer, said the following.

“What’s the use of having developed a science well enough to make predictions,” Rowland said, “if all we’re willing to do is stand around and wait for them to come true?” We do have tools to tackle the issues. However, with indifference we have to keep the tools in a locker and be mere spectators as the problem spreads and wounds deepen. That too is an act of indifference.

I am sure those who are here do wish to see this culture of indifference disappearing or at least abating. While we understand the issue to be indifference, the onus may be upon the scientists too to push policymakers and tackle the indifference to make a real difference.

[The writer is Professor of Chemical and Process Engineering at the University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka. With an initial BSc Chemical engineering Honours degree from Moratuwa, he proceeded to the University of Cambridge for his PhD. He is the Project Director of COSTI (Coordinating Secretariat for Science, Technology and Innovation), which is a newly established State entity with the mandate of coordinating and monitoring scientific affairs. He can be reached via email on [email protected].]