Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday, 12 November 2015 11:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In the end it took only five days for the unthinkable to happen.

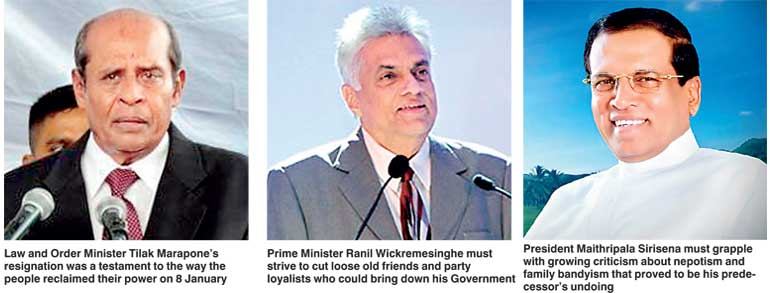

For the first time in recent memory, a minister of Cabinet rank was forced to tender his resignation following a massive public outcry over his attempted defence of a private company implicated in a major arms scandal. After five days of intense public and civil society pressure and the threat of mutiny within their own ranks, Government leaders realised the wolf was at their door.

For the first time in recent memory, a minister of Cabinet rank was forced to tender his resignation following a massive public outcry over his attempted defence of a private company implicated in a major arms scandal. After five days of intense public and civil society pressure and the threat of mutiny within their own ranks, Government leaders realised the wolf was at their door.

When Minister Tilak Marapana informed the Prime Minister and the President that he would be resigning, neither protested. Hoist as they were by their own petard, neither Maithripala Sirisena nor Ranil Wickremesinghe could afford to keep the Minister inside their Cabinet while pretending to be delivering good governance. Given Prime Minister Wickremesinghe’s position on the Central Bank bond controversy, the prospect of his sacking Marapana seemed remote. But Wickremesinghe confidants said the Prime Minister had been in agreement since last week that time was up for his Law and Order Minister after his outburst in Parliament last week.

Tilak Marapana was Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe’s appointee for the job of overseeing Law and Order and Prison Reform after the UNP-led alliance clinched the most number of seats in the 17 August Parliamentary election. Marapana is an unelected legislator; a senior lawyer brought to Parliament through the UNP National List. Before the UNP-led coalition claimed victory in August, Marapana was already ensconced within the new Government, as Advisor to the Prime Minister. As a former Attorney General and Solicitor General, it was believed that President’s Counsel Marapana would be helpful in the mammoth task before the new administration – to act against a host of major corruption scandals that had ultimately proved fatal to the Rajapaksa regime.

Well-known facts about the former Law and Order Minister included his proximity to President Mahinda Rajapaksa, who was prone to seeking legal advice from the senior lawyer on matters of crucial national importance. Highly-placed sources within the previous administration claimed he had been one of the legal advisors who counselled the appointment of three international war crimes prosecutors as foreign experts contracted by the Government to “assist and advice” the Paranagama Commission on Disappearances.

With the appointment of the international experts, the Commission of Inquiry on Missing Persons led by the former High Court Judge Maxwell Paranagama had its mandate enhanced in July 2014. Paranagama and his two other Commissioners were now also being tasked with determining whether there had been any violations of international humanitarian law and/or civilian casualties that could not be put down to ‘collateral damage’ during the final months of the war.

In effect, it was to be the Rajapaksa regime’s counter-offensive against the UN, which was set to start its own Human Rights Council mandated inquiry into allegations that war crimes had been committed during the latter years of the war. The use of war crimes experts Desmond De Silva QC, Geoffrey Nice and David Crane – all three having assisted the International Criminal Court to indict war criminals – to assist this domestic inquiry, was to lend credibility to the Commission’s probe.

In effect, it was to be the Rajapaksa regime’s counter-offensive against the UN, which was set to start its own Human Rights Council mandated inquiry into allegations that war crimes had been committed during the latter years of the war. The use of war crimes experts Desmond De Silva QC, Geoffrey Nice and David Crane – all three having assisted the International Criminal Court to indict war criminals – to assist this domestic inquiry, was to lend credibility to the Commission’s probe.

In Parliament earlier this year Tamil National Alliance (TNA) MP M.A. Sumanthiran flayed the new Government for its continued use of Sir Desmond at an astronomical fee to assist the Paranagama Commission. Similar incredulousness was expressed behind the scenes by Parliamentarians who had strongly backed the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe combine to defeat the Rajapaksa regime in January, about former friends of the Rajapaksa regime who had managed to win the confidence of the new Government.

This list included Marapana and Member of the EU Parliament Niranjan De Silva Deva Aditya, an individual with strong loyalties to the former regime. Both Marapana and Deva Aditya had been appointed advisors to Prime Minister Wickremesinghe soon after the new Government was sworn in after the 8 January presidential poll. Both individuals, highly-placed sources said, had a role in bringing Sir Desmond in as an ‘international advisor’ in 2014.

UNP moles

Cabinet Spokesman Dr. Rajitha Senaratne alluded to these strange phenomena at last week’s briefing, when he told reporters about the uncanny turn of events that had led to UNP members ratting on their party to the Rajapaksa regime, now calling the shots in the new Government.

“Back when we were in the Mahinda Rajapaksa Cabinet, to our great amusement these UNP Working Committee members would call the former President and put his phone on loudspeaker to allow us to hear the entire proceedings of the meeting. We used to all sit around and laugh at the deception then. Now these same individuals are back in top positions in this Government as well,” he explained.

To exacerbate matters, and to the horror of freshman UNP MPs and junior legislators and party-men, other ‘old-timers’, officials and politicians associated with UNP Government excesses in the past were also trickling in and taking their seats at the table. This was effectively, the UNP old guard, men who had no place in the new era of ‘yahapalanaya’ politics. They neither understood the language nor shared the ideology that had spurred a national movement to oust the Rajapaksa administration in January. These were, and are, the ‘business as usual’ types, relics from an era when politicians and their cronies were held to a less exacting standard than the benchmarks being aspired to in post-January 8 Sri Lanka.

Typically, beginning with Minister Marapana, these vintage politicos are threatening the survival and credibility of a Government that was ushered into power on a mandate to fight corruption and bring transparency, integrity and accountability into governance. Public anger at the perceived betrayal of this mandate is unprecedented. Through vibrant and empowered civil society organisations and the ubiquitous power of social media, public disillusionment is finding expression like never before.

A brewing controversy

While the former Law and Order Minister’s outrageous remarks in Parliament last Wednesday (6) precipitated calls for his immediate sacking and his eventual resignation ahead of a more ignominious departure, the fact remains that senior members of the current Government were being implicated in the Avant-Garde Maritime Services scandal as far back as February this year.

The shadowy security firm has immensely deep pockets – CID sleuths found the company was raking in up to Rs. 15 million daily from its floating armoury operations – and its tentacles have reached several tiers deep within the new administration. But in a strange coincidence, the first controversy regarding the Avant-Garde investigation also involved the same two Ministers who came out so strongly in defence of the company in Parliament last week. At the time Marapana was only an advisor to the Prime Minister, but Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe held the same portfolio he holds today – that of Justice Minister.

The first signs that something was amiss emerged at a National Executive Council meeting in February, attended by JVP Leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake, who is a member of the all-party council meant to be an oversight body for the Government.

Dissanayake had also been appointed by the Prime Minister to the Committee against Corruption, which was to track the ongoing corruption probes and provide necessary guidance and follow up to the investigating authorities and Government prosecutors.

After several weeks without progress on Avant-Garde or arrests in connection with what looked to be a fairly clear-cut case of an unauthorised lease of Government-owned weapons to a handpicked private security firm, Dissanayake fired several salvos against the representative from the Attorney General’s Department, an individual who remains a senior official at the department. The JVP Leader was particularly irked that Nissanka Senadhipathi, the controversial Chairman of Avant-Garde Maritime Services and a former Major attached to the Commando unit, had been able to obtain his passport from the Courts and permitted to travel overseas.

Senadhipathi’s passport and that of Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa and several others had been impounded as soon as investigations began into the Avant-Garde case. Bombarded and harangued by Dissanayake, the representative from the AG’s Department finally threw up his hands and said two senior members of the Government had intervened to request Police officials to refrain from objecting when Senadhipathi made an application to Court requesting his impounded passport.

The top Government lawyer explained to the Council that it would have been better if Senadhipathi’s passport had not been returned while the investigations were underway. But since the Police did not object, Senadhipathi was permitted to travel to Nigeria and several other countries, purportedly for business. Sleuths and analysts suspected at the time that the Avant-Garde Chairman could have been on a mission to suppress information regarding the company’s operations off the coasts of those states. Prime Minister Wickremesinghe and Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera were also present during the explosive meeting, the JVP Leader claims.

Called out in February 2015

An irate Dissanayake subsequently publicly called out Minister Wijeyadasa and then Government Advisor Marapana as being named by the senior official from the Attorney General’s Department, implicating both officials in the events leading up to the release of Senadhipathi’s passport. The accusation levelled by the senior Government lawyer would be even more damning if Marapana was still functioning then as counsel for Avant-Garde.

Back in February 2015 then, the JVP Leader was already flagging members of the Government whose allegiances may have been further exposed last week, when they chose to respond to Dissanayake’s scathing speech about the bungling of corruption investigations and deal-making with criminal elements by the new Government, including the Avant-Garde case.

Marapana, who admitted he had served as legal counsel for the company, pronounced on the legitimacy of the company’s operations, while Justice Minister Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe claimed he agreed with the Attorney General’s position that there were no charges to be filed against the company, and declared that he had prevented the arrest of the former Defence Secretary in connection with the case. Minister Rajapakshe has continued to defend this position, despite growing criticism against him, in several newspaper interviews he has given since his disastrous outburst in Parliament last week.

The positions taken by the two Ministers fly in the face of the Government’s commitments to uphold the rule of law and deal ruthlessly with corruption. Prime Minister Wickremesinghe in an interview with a foreign journalist in February 2015 called the Avant-Garde case “Sri Lanka’s Blackwater,” alluding to the private US security contractor involved in a major scandal in Iraq in 2007, which killed 17 civilians in Baghdad.

While the law is often thought to be a complex thing, better navigated by experts and professionals, the law is also grounded in morality and an inherent sense of right and wrong. Today’s complex legal arguments by Government lawyers and Avant-Garde defenders like Marapana cannot compete with the gut instinct that prevailed in the minds of law enforcement, politicians and the public that something was very, very wrong with the way the Avant-Garde had conducted its affairs. Before the Commission of Inquiry into Large Scale Corruption, senior members of the Defence establishment have now testified to the irregularities in the deal made between the Government and the private security firm.

Emblematic corruption

The Avant-Garde case, in many ways, is emblematic of Rajapaksa corruption, impunity and corporate practice. The private company, run by a former military official, submitted an unsolicited proposal that was authorised without evaluation or tender procedure, by the former Defence Secretary. Weapons were being provided to the maritime security firm that was maintaining floating armouries, through Rakna Arakshaka Lanka Ltd. (RALL), the Defence Ministry-owned company that was Secretary Rajapaksa’s pet project.

In the first flush of investigations, the CID found thousands of extra weapons on-board the Avant-Garde ship than had been authorised by the Defence Ministry. The proposal to provide Government-licenced weapons to a private security firm had no Cabinet sanction and no Parliamentary oversight. It was a contract between the Sri Lankan Government and a private company that had been made in the shadows, the way the Rajapaksa administration preferred to do business.

Long before the AG’s Department told Court there was no case to be filed against Avant-Garde Maritime Services, Additional Solicitor General Wasantha Navaratne Bandara in a memo to the Attorney General explained the provisions under which Senadhipathi, Defence Secretary Rajapaksa and several others could be prosecuted under (1) The unauthorised Importation of Fire Arms to Sri Lanka (under the Prevention of Terrorism Act and Firearms Ordinance), (2) Possession of Firearms and ammunition without valid licenses (under the Firearms Ordinance and Explosives Act) and (3) Conspiracy, aiding and abetting to commit the above offences. The memo was subsequently leaked to a news website earlier this year.

For reasons best known to the Attorney General’s Department and the Government alone, the memo was dismissed and the fresh opinion from the Department, submitted to Court, was that Avant Garde could not be prosecuted under any of these provisions. Instead the Attorney General is hoping to nab Avant-Garde on money-laundering laws.

The seizure of a second Avant-Garde vessel off the coast of Galle in October has complicated the case. Police have found that the vessel did not possess the necessary clearances and licences to dock with its deadly cargo in Galle. Marapana, who staunchly defends the company with regard to the vessel raided in January, refuses to comment on the new ship under investigation. What is crystal clear now is that Avant-Garde Maritime Services had continued its business with the Sri Lankan Government over the past 10 months, their authorisation from the previous regime still valid and uncontested by the new administration.

Yesterday, in the face of mounting public criticism and aspersions being cast on President Sirisena and Prime Minister Wickremesinghe in connection with the scandal that both leaders strongly deny, the Government has finally cancelled all dealings with Avant-Garde Maritime Services. The company has been ordered to hand over all weapons on-board its armouries to the Sri Lanka Navy. At a meeting chaired by President Sirisena yesterday with investigators, lawyers and military officials, it was found that the company had not been following regular procedures and Government regulations in its floating armoury operations.

Difficulty of reform

The Avant-Garde scandal has laid bare the difficulties inherent to reforming and transforming a political culture that has relied and thrived for so long on well-oiled palms, payoffs and returning favours. Prime Minister Wickremesinghe and President Sirisena are both men who belong to the old political culture, with old friends to ‘take care of’ and old scores to settle. But ironically, they are also the two men tasked with altering the status quo in Sri Lankan politics. This struggle between the old and the new is likely to play out over and over again, as the Government strives to find its feet and define its true character. While Sirisena must grapple with growing criticism about nepotism and family bandyism that proved to be his predecessor’s undoing, Wickremesinghe must strive to cut loose old friends and party loyalists that could bring down his Government. These are not easy demons to fight but neither has much choice.

‘Yahapalanaya’ is a state of mind, and it was a concept both leaders strove hard to inculcate in the people when they were fighting a powerful and corrupt incumbency back in January. Today the notion appears to have taken hold, and the Government finds itself a hostage to its own mantra. Because of the platform on which it was swept to power, the Government remains still sensitive to public opinion, and interestingly, the outrage and backlash from the movement of civil society groups that propelled the new regime into office in January.

Marapana’s resignation came a day after the nation was united in grief at the passing of Ven. Maduluwawe Sobitha Thero, the architect and spiritual leader of the 8 January struggle. In recent years, the monk had agitated tirelessly against the abuse of power and corruption that was robbing Sri Lankans of an equitable and prosperous future. The saffron he wore gave Sobitha Thero a kind of immunity no one else enjoyed in Rajapaksa Sri Lanka. He used that space to mobilise and lead a movement for change that unseated a deeply-entrenched incumbency and restored power to the people. Despite disillusionment and disappointment, so far they haven’t looked back. Last time around, public apathy had proved to be an almost fatal mistake.

The resignation of the Law and Order Minister was a testament to the way the people had reclaimed the true extent of their power on 8 January. Old guard politicians who cosied up to the previous regime, who cannot fathom the risks taken 11 months ago to effect change and shift the balance of power back to the people, will not survive the citizens’ wrath when they seek to reverse those gains. For now, politics as usual will not be tolerated. For now, the citizen is awake and vigilant. For now, the spark Sobitha Thero kindled is a burning flame.