Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Friday, 17 February 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

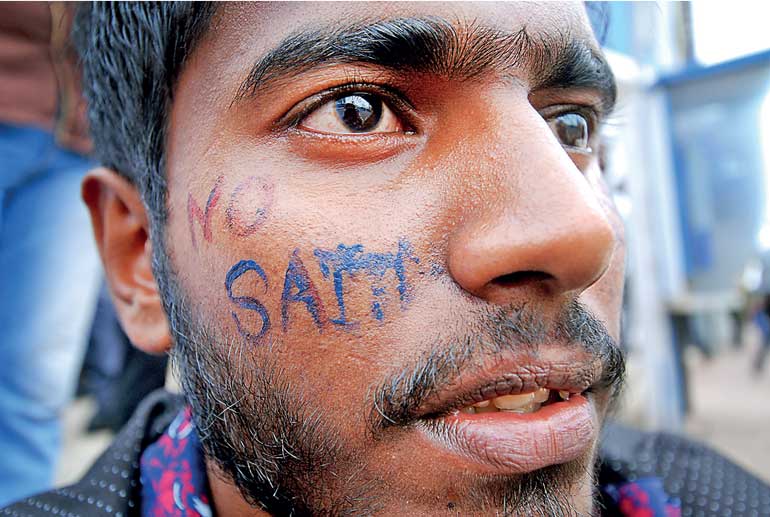

A protest by State university students, calling on the Government to intervene and close SAITM. While there is a dire need for more doctors, we have thousands of able and willing youngsters who miss opportunity for a free-of-charge medical education by a thousandth fraction of the Z-score – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

A protest by State university students, calling on the Government to intervene and close SAITM. While there is a dire need for more doctors, we have thousands of able and willing youngsters who miss opportunity for a free-of-charge medical education by a thousandth fraction of the Z-score – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

The GMOA has been the most vocal component of the medical establishment in its opposition towards expanding medical education opportunities through non-State options. The one and only non-State option available locally is none other than the much-maligned medical degree offered by SAITM (or the South Asian Institute of Technology and Medicine).

The exorbitant cost of a SAITM medical degree education has fuelled sentiments against the institution by the public, though the very same public is relying on non-State options in every other sector. Catchy slogans against SAITM have drowned out the fact that fees are higher than necessary at SAITM because of the costs incurred by the institution to fight a powerful medical monopoly made up of at least two other actors with vested interests.

The judgment of the Sri Lanka Appellate Court in favour of a medical graduate of SAITM who sought justice against SLMC (or the Sri Lanka Medical Council) has exposed the essential role of that institution in this monopoly. The Appellate Court judgment should be required reading for anybody who has a hard time believing the duplicity and/or the incompetence of the supposedly premier regulatory body in the medical sector.

Now the deans of the faculties of medicine at public universities have joined the fray, making contradictory arguments to pass judgment on a peer private institution, exposing their own weaknesses in the process. The trio of GMOA, SLMC and the Medical Deans is what I would call the iron triangle of a medical monopoly.

An iron triangle is a situation where three key stakeholders in a sector are working together to stymie outside efforts to reform the sector (Gordon Adams, 1981). I have used the term before in the context of higher education in general, but its application to the medical sector with SLMC, GMOA and Medical Deans as the key stakeholder might be just the explanation we need to explain the current bizarre situations in our medical sector.

SLMC or Sri Lanka Medical Council is a statutory body established for the purpose of “protecting health care seekers by ensuring  the maintenance of academic and professional standards, discipline and ethical practice by health professionals who are registered with it.” SLMC’s behaviour regarding SAITM has opened doubts about the professionalism of the council. As noted by the Court of Appeal in its Court Order CA/WRIT/187/2016:

the maintenance of academic and professional standards, discipline and ethical practice by health professionals who are registered with it.” SLMC’s behaviour regarding SAITM has opened doubts about the professionalism of the council. As noted by the Court of Appeal in its Court Order CA/WRIT/187/2016:

“The report submitted by the SLMC Inspection Team was without legal basis, exceeding the powers conferred on the SLMC, because there are no prescribed minimum standards for medical education by any university or degree awarding institute in the country, which have been gazetted and approved by Parliament, as required by the Medical Ordinance.”

Yet, SLMC has given recognition to a medical degree program at the Kotelawala Defence University, with only two pages of review relying on the promise of a hospital to be built. In contrast, they have conducted lengthy inspections of the medical degree program at SAITM according some unspecified standard and judged the program as unworthy (See pages 27-28 of the judgment). As the Court Order notes, the observations in the report are favourable and includes suggestions for improvement, but “[the] observations do not match with the final recommendation made.” The recommendation being to deny provisional registration to SAITM graduates.

As Dr. Pradeep de Silva, an educator at the Ragama Medical Faculty noted in an article published in Lankadeepa on 13 February, the Sri Lanka Medical Council is an archaic institution with archaic and inefficient practices. According to him, the council essentially consists more or less of the medical deans of public universities and the dean of Faculty of Medicine at the Kotelawela Defence University.

Other categories of doctors are elected to the council but the election procedures are not conducive to participation by the full membership. Apparently, the council does not even have a proper list of medical specialists registered in Sri Lanka. It is time the Government considered amendments to the SLMC Act to shape up the organisation by mandating, for example, that one-half of the council should consist of lay persons with a wider range of expertise and experience.

The GMOA has been vicious in its opposition to SAITM calling it an illegal institution and demanding nothing short of its abolishment. While SLMC is suggesting more clinical training for students at SAITM, the GMOA is making everything possible to block the students from access to Government hospitals.

Established in 1945 as a professional association, the GMOA proudly claims to be the first medical trade union to launch a strike:

“The water-shed in trade union work was reached in 1964 when the membership of the day overwhelmingly voted for the institution-of trade union action to increase salaries. This was the first time that doctors in any part of the world had struck work. The action was successful and the Government awarded an increase in salaries and limited form of [private] practice (Channel Practice).”

Fighting for better working conditions and better pay is well and good, but the present actions of the GMOA obstructing entry to the profession should receive scrutiny by experts for its legality or ethicality.

The deans who issued a joint statement on SAITM a few days ago are from of the Faculties of Medicine in Colombo, Peradeniya, Ragama, Karapitiya, Jayawardanapura, Jaffna, Batticaloa and Rajarata, all of them being public institutions. The deans recommend, amongst other things, that “SAITM should be compelled by the Ministry of Higher Education to suspend admission of medical students until it obtains the necessary compliance certification from the SLMC.”

It is rather presumptuous of these medical deans to reject a peer medical faculty in this manner. Have the public medical faculties headed by these deans been evaluated by SLMC and issued similar certificates of compliance? As Dr. Pradeep de Silva notes in his column in Lankdeepa, just because students in these medical faculties get access to patients in teaching hospitals does not mean that they get a proper training. Apparently, clinical teams in some faculties now may consist of 40 students in one group. Has the SLMC looked into those practices and barred the registration of graduates from such programs?

In fact, teachers at our public institutions seem to think that by virtue of being public employees, we have to accept them as being of good quality. I have written in the Sinhala media about quality issues in Faculties of Arts in the public sector based on a survey of faculty quality that I carried out as a consultant to the University Grants Commission in 2003. I am not aware of any external assessment of our Faculties of Medicine.

The medical deans rightly ask for “regulations prescribing minimum standards for medical education in all HEIs that are empowered to award medical degrees” in their joint statement, but in the same document they pass judgment on SAITM based on an improper assessment by the SLMC. These same deans are members of SLMC we should note.

Sri Lanka leads in health and sanitation indicators in South Asia and the unsung heroes in these achievements are the public health inspectors and public health nurses and midwives. The doctors and support staff at most public hospitals too are doing an adequate job with limited resource.

Sri Lanka is doing well on controlling communicable diseases as well. However, our non-communicable disease rates are increasing. As the World Health Organization says, these diseases are “driven by forces that include ageing, rapid unplanned urbanisation, and the globalisation of unhealthy lifestyles.”

To face these challenges we need doctors who can spend more time discussing prevention of diseases and lifestyle changes, but Sri Lanka has a shortage of doctors, in rural areas in particular. In urban areas too, patients wait long hours, particularly when they are seeking channelling services or private consultations with Government doctors. What we experience as patients is hastiness to prescribe drugs where perhaps a good listen by the doctor followed by lifestyle advice and continuing care by the same doctor would have been the right thing to do.

Talking to Sandeshaya, the Sinhala service of BBC on 11 July 2016, Dr. Palitha Mahipala, the Director General of the Health Services Department then had said that there is a shortage of 2,500 doctors, particularly in rural areas. As the country develops we can expect the demand for doctors to increase in parallel, he said.

While there is a dire need for more doctors, we have thousands of able and willing youngsters who miss opportunity for a free-of-charge medical education by a thousandth fraction of the Z-score. If the SLMC and the deans have their say, these youth will have to wait till the SLMC gets its act together. If the GMOA and the ultra-left political groups with their captive audience of submissive university students have their way, it is free-of-charge of education or nothing for the rest.

The behaviour of SLMC, GMOA and Deans of the public medical faculties makes one wonder whether, knowingly or otherwise, these institutions are colluding to keep competition at bay.

GMOA is a trade union, skating too close to ‘closed-shop’ behaviour which is now illegal for trade unions in most countries. As for SLMC apparently it has to go back to kindergarten to learn about regulating. The Deans of Medical Colleges seem to be viewing the medical profession from the comforts of the public sector where students are brought to their doorsteps and all expenses are paid by the Government.

The problem lies not with individual institutions or individuals but the structuring of medical sector in Sri Lanka where medical doctors are able to exert undue control over the sector. The Appellate Court decision has opened a space for those enlightened beings within the sector and civil society activists to step in and pressure the Government to reform the sector. Following are some proposals for further discussion:

nRemind the SLMC that they are mandated to develop standards for medical education and apply them to all higher education institutions consistently and fairly.

nAward no-interest loans to at least 100 students who missed a free medical education in 2017 by a few decimal points in their Z-scores; Allow them to use the funds for a medical education anywhere with the loans being payable by service in rural areas after their graduation.

nRestructure the SLMC to become a more modern and efficient institution able to fulfil its obligations; Appointing half of the members of the Council out of eminent personnel outside of the medical profession as in the General Medical Council of UK, would be a good start.

nSet up a system to recover costs from medical graduates who study at public expense and leave the country or join the private sector; Channel those funds, and more, to public medical education.

nAssist the private medical institutions with land, low-interest loans and training facilities so that they can offer a medical education at lower costs; Stop harassing them; Make the best of these private investments through reasonable mandates that direct the investors towards public interest objectives.

nIn the long term, establish a Higher Education Funding Agency to award grants and/or loans for higher education areas of national interest.

Note: The statements in this column are not meant to denigrate those good doctors in the public sector who provide medical services under difficult conditions and are striving to reform the sector.