Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Wednesday, 9 December 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Those coming from a different and perhaps saner environment will find it difficult to understand why the medical profession in Sri Lanka is threatening strike action on the basis of a withdrawn privilege; the right to import a duty free car. In more evolved environs it will be very unusual for there to be a tax imposed, and then to have various groups exempted from it due to pressures exerted on the government by them.

It will also be unacceptable for a government to impose a general tax on the people and exempt their MPs from its application, one of the reasons being the obvious hypocrisy of such a course of action. The imposer of the tax does not want to be subject to it! In their understanding (those coming from saner environments) tax is the primary way of contributing towards the society you live in, paying your dues to the polity, sharing in the wider development and the providing of services.

The doctors in Sri Lanka, for that matter doctors anywhere in the world, do not fall within the definition of the needy or underprivileged. On the contrary, as a group, they command a life style far above the average. While those doctors in government service are on a high salary scale relative to other public servants, in private practice money just flows in to their pockets.

The demand for medical attention is such, whether really needed or not is another issue, which a doctor rarely spends more than a few minutes with a patient. (It is said that the vast majority of those who crowd medical clinics would have been cured naturally with a few days rest and perhaps a Disprin or two – a case of the ignorant unnecessarily elevating a service provider.)

While the standard of basic medical service in the country is claimed to be good, if compared with the poorer countries, it is still a fact that those who can afford it, including the politicians, prefer a place like Singapore for treatment where we are told the professional standards are a world apart.

While their very function arms them strongly in the demand for duty free concessions for imported vehicles, we must not forget the rest, including those earning fixed salaries in both public and private sector; hard pressed to buy their family vehicle on account of the exorbitant import duty imposed. The doctors, have the coercive means to demand a privilege and are well aware that to deny them will be costly for the government. Given the social and political realities of the country, the government must but succumb to the demands of the doctors.

To a person, every doctor in Sri Lanka, from kindergarten to becoming a doctor has studied at the cost of the tax payer. Compared to other disciplines, study of medicine is expensive. For each doctor, the tax payer of a poor nation has spent loads of money. Obviously, that is not enough, a life time of concessions, priority and privileges must be provided.

But in the backdrop of an inescapable social decay, this uninspiring scenario of unionised doctors threatening strike action is not exceptionally grim. The tragedy is that such conduct could even be considered as representing the everyday moral temper of our times, the way to do things, the standard. In no way are the doctors solely responsible for the attitudes, habits and outlook that brought about this culture. The inclination to squeeze out any benefit from the system, using ones position to obtain every advantage, exploiting each situation to gain profit in one form or the other, owes its legitimacy to another much more powerful phenomenon: the political mores that grips our society now.

At least the doctors are in a position to argue that they are practicing medicine in order to earn their bread and butter and perhaps a little more .It is nothing more than that. Hippocrates lived in Greece 500 years B.C. and any oath in his name has little bearing in our distant and disparate culture and clime! Given the prevailing ethos, such fine oaths and ideals have no meaning or bearing.

The politician, on the other hand, tells us that he is not taking to politics to make a living. He has ideas, resources and skills which will make our lives better. He only wants to enrich us, not be enriched by us!

Clearly the political establishment of our country has no moral right to ask the doctors to pay the duty on their imported vehicles. How could they, when the first thing the politicians, who have the power to decide such things, have done is to exempt themselves from paying the duty on their cars? It is not as if they are lacking in vehicles. The entire fleet of their Ministries is there to be used and abused by them. Even their family members are driven about in the sleekest vehicles available in the market. Those vehicles are only one aspect of the plethora of benefits that our so called leaders have allocated to themselves. All that is not enough, they must also be given duty free vehicles which can be sold later at a tidy profit.

Undoubtedly, the lowering of moral restrains in public matters reached its nadir during the Rajapaksa regime. When it came to the Rajapaksa family, there was no distinction between private and public. Any need or wish that occurred to a Rajapaksa was immediately turned in to a public cause. In the ensuing hullabaloo, businessmen, pressure groups, lobbyists jostled with each other to make their deals with the family. The only requirement, which was absolute, was the grovelling acknowledgment of the primacy of the ‘first’ family. It is amazing that those guilty of such conduct still function, with no accounting for their abjectness before something so primeval and faulty. With that heavy cloud now lifted, it is difficult to imagine that village ruffians, hangers on and con-men; so limited, self-content and trivial, held the fortunes of 21 million people firmly in their coarse hands for so long.

With the Rajapaksas gone, the vulgarity of a ruling family has receded. But alas, nepotism, politicisation and abuse of power which they thrived on and attempted to legitimise, remain very much the theme of the times. The only difference seems to be that politicians are now obliged to publicly condemn nepotism and corruption. But in the everyday reality we see not only the continuation but even the encouragement of these evils. Clearly, the stubborn stains on the minds, institutions and systems so soiled, are not that easy to remove.

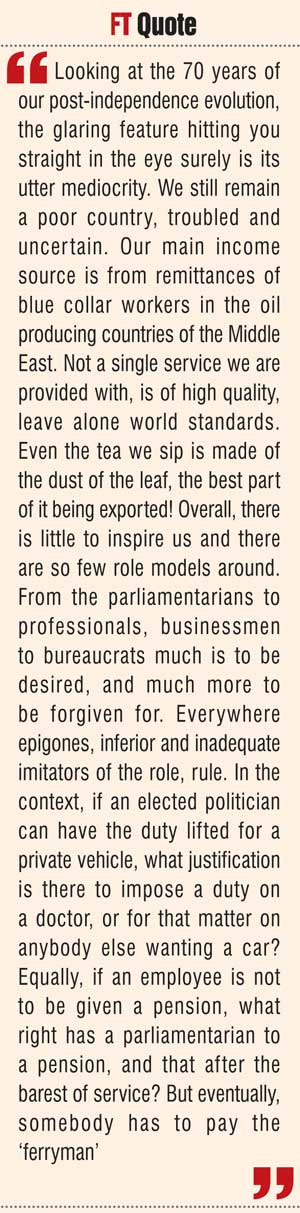

Looking at the 70 years of our post-independence evolution, the glaring feature hitting you straight in the eye surely is its utter mediocrity. We still remain a poor country, troubled and uncertain. Our main income source is from remittances of blue collar workers in the oil producing countries of the Middle East. Not a single service we are provided with, is of high quality, leave alone world standards. Even the tea we sip is made of the dust of the leaf, the best part of it being exported! Overall, there is little to inspire us and there are so few role models around. From the parliamentarians to professionals, businessmen to bureaucrats much is to be desired, and much more to be forgiven for. Everywhere epigones, inferior and inadequate imitators of the role, rule.

In the context, if an elected politician can have the duty lifted for a private vehicle, what justification is there to impose a duty on a doctor, or for that matter on anybody else wanting a car? Equally, if an employee is not to be given a pension, what right has a parliamentarian to a pension, and that after the barest of service?

But eventually, somebody has to pay the ‘ferryman’.

Nearly every morning I cross a train coming towards Colombo. It is jam-packed with office workers, some even hanging on dangerously to the door handles and windows of the fast moving train. In their desperation to be on time, heavy risks are taken. Accidents are common on such crowded trains. It is sad that the bill ultimately ends up with people like those commuters, powerless and helpless.