Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Thursday, 6 October 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

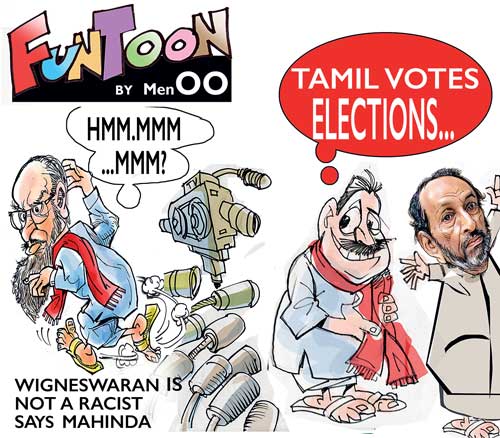

How did the sitar-playing, sage-like Chief Minister of the Northern Province fall within the grasp and influence of Tamil nationalists and bankrupt politicians in only three years? And can the TNA bring him back into the fold?

When Canagasabapathy Visuvalingam Wigneswaran took over as the country’s first democratically elected Chief Minister of the war-torn Northern Province, bureaucrats were awed by his stature and personality.

Soft strains of classical sitar music played over the sound system of the Provincial Council chamber in Kaithady, Jaffna shortly before the Chief Minister made his maiden address at the newly elected assembly. Bureaucrats chose the music carefully because Wigneswaran himself was a ‘master sitarist’, and they hailed the new leader of the Northern Province as a ‘rajarishi’ or Chief Sage. An erudite man of deep religious faith, Wigneswaran had the unmistakable air of statesman about him when he was first elected to office.

In an election campaign fraught with tension, abuse and military led intimidation, the people of the Northern Province voted overwhelmingly for the Tamil National Alliance in the provincial council polls of September 2013. The TNA won 30 out of 38 seats – a two-thirds majority – in the Northern Provincial Council being constituted for the first time.

Running the provincial administration was never going to be easy. Contentious devolution arrangements, a military Governor and an administration in Colombo with a solid mistrust of ethnic minorities made for a rocky road for the new provincial assembly. The NPC was also the first real test of the India designed 13th Amendment to the constitution that offered limited powers over regional affairs to provincially elected leaders, in the postwar period.

TNA Leader R. Sampanthan’s choice for Chief Minister seemed like a masterstroke at the time. Wigneswaran was born in the capital Colombo and schooled in Kurunegala and Anuradhapura before entering Royal College – the educational institution most closely associated with the country’s ruling classes. He speaks Sinhalese fluently and during his career in the judiciary, Wigneswaran served in courts in the north and south. Having lived most of his life in the ethno-religious melting pot that is the capital, Wigneswaran was a far cry from an insular Tamil regional politician.

The TNA’s choice for Chief Minister was hailed widely in moderate circles of the South. There was certainty that Wigneswaran would bring to the new provincial administration the measured political approaches TNA leadership had adopted in the national arena in the post-war period.

In some ways, Wigneswaran carried not only the hopes of the Northern people who directly elected him but moderates and progressives in the South, who were backing greater devolution and political autonomy for the Tamil dominated regions. ‘With politicians like Wigneswaran at the helm of provincial affairs, what was to be feared from offering greater control over their own affairs to the periphery’ was the crux of the moderate argument in the south. Some analysts however warned that Wigneswaran’s lapses on the campaign trail 2013, when he hailed Vellupillai Prabhakaran as a hero like Keppetipola, were a dangerous sign of his willingness to sacrifice his principles at the altar of populism.

2014: Staying the course

In his first year in office, the Chief Minister appeared to be living up to most of this expectation. There were allegations that the NPC was not doing enough to improve livelihoods or public infrastructure that had a direct impact on the lives of some 450,000 people who had reposed their faith in the TNA-led administration. But in 2013-2014, this was easily chalked up to intransigence by the Centre led by President Mahinda Rajapaksa, and powers afforded to the Northern Province Governor, retired Major General G.A. Chandrasiri who would continue to hold the provincial bureaucracy in his vice-like grip even after the election of the new Council.

Still, as the most recently elected representative of the Northern people, Wigneswaran retained a certain stature in national politics. Visiting foreign officials rarely skipped a meeting with the Chief Minister, affording him greater status than elected leaders of other provinces. Throughout most of 2014, Wigneswaran stayed the course, highlighting the grievances of the Tamil people and working collaboratively with the TNA.

The Chief Minister’s transformation began around the time that the Rajapaksa administration was ousted in a shocking election result in January 2015. On 4 February 2015, the new Government held Independence Day celebrations in a markedly different way, making a special statement of peace in solidarity with all victims of the 26-year civil war. For the first time since 1976, representatives of the country’s main Tamil party attended the Independence Day function, signalling the potential for a new era of cooperation between the Sinhala and Tamil political leadership.

February 2015: First sign of rebellion

Just days later, in the wake of sharp divisions within the TNA about Sampanthan’s decision to attend the Independence Day function, Chief Minister Wigneswaran fired the first salvo.

On 10 February 2015, the NPC led by Chief Minister Wigneswaran adopted the now infamous ‘Genocide resolution’ that extremist elements in the Council had been agitating for over a period of time. Until February 2015, Wigneswaran had resisted pressure to bring this resolution to the Council, but his capitulation on this front seemed to be one of the first signs of the Chief Minister’s gradual process of radicalisation.

Disillusioned with the Government the TNA helped to bring to power, Wigneswaran opted to stay “neutral” during the 2015 Parliamentary Elections, while at the same time tilting heavily towards urging support for Gajen Ponnambalam’s hardline Tamil National People’s Front (TNPF).

As for his provincial administration, he allowed it to lapse into complete ineffectuality. The NPC has passed few statutes that make a tangible difference to the lives of people on the ground in the war-battered region. Fisheries is a devolved subject under the 13th Amendment and hundreds of South Indian fishing trawlers light up the horizons in islands off the Jaffna peninsula every week, stealing the livelihoods of impoverished Northern fishermen and depleting Sri Lanka’s marine resources. But the NPC has done little to address the problem or even to lobby the Centre for solutions, perhaps fearing pushback from Tamil Nadu, where Tamil hardliners find their greatest ideological support.

Wigneswaran also squandered a golden opportunity to make a difference locally, while retired diplomat Siri Palikhakkara functioned as Governor of the Northern Province for one year after the new Government took office in Colombo. An efficient bureaucrat with moderate leanings, Palihakkara promised the Chief Minister he would negotiate with the Central Government to ensure the NPC had the capacity to function effectively as a regional administration. But the Chief Minister, increasingly in the thrall of a nationalist wave sweeping across the North and finding voice for the first time since the end of the war with the easing of military suppression in the region, would have none of it.

Unrecognisable Chief Minister

The only mark the NPC has made having just completed half its term has been to pass several controversial resolutions, apparently with the sole aim of antagonising the Centre and the southern polity, and angering the TNA’s international partners who view this conduct as largely counterproductive to finding a permanent political solution to longstanding Tamil grievances.

Twenty months after the first signs of rebellion with the ‘Genocide’ resolution, the moderate and measured Chief Minister elected in September 2013 is almost unrecognisable today. A coterie of Tamil hardliners drawn from the ranks of Jaffna’s powerful civil society, ultra nationalist political parties and radical academics has cast a net around the Chief Minister, alienating him from TNA moderates and driving him towards an ever more nationalist political agenda.

Two weeks after he decided to lead the controversial ‘Eluga Tamil’ (Rise, Tamil!) rally, Sri Lanka’s first Northern Province Chief Minister C.V. Wigneswaran remains in the eye of a relentless political storm. Wigneswaran has attempted to walk back some of the more controversial slogans of Eluga Tamil, claiming his remarks at the rally were misinterpreted by the southern media. Reading a statement out in Sinhalese at the National Sports Festival in Jaffna, Wigneswaran tried to clarify that it was unauthorised Buddhist structures being erected in the north with the support of the army that he was opposed to. According to the Chief Minister, these constructions did not have the necessary approvals from the provincial administration.

Controversial slogans

But the clarification notwithstanding, there is no denying that the organisers of Eluga Tamil used the two most controversial slogans of the rally in the propaganda leading up to the event. Alleged Sinhalese colonisation and the construction of Buddhist shrines in the Hindu-dominated region were the main themes of the Chief Minister’s open letter published days before the rally, in which he called on the Tamil people to participate in the event.

Concerns about Sinhalese settlements being created with the support of the military and the many Buddhist shrines cropping up in the Northern Province in an alleged attempt to change the ethnic demographic and subsume the Tamil cultural identity of the region are hardly unfounded. But Eluga Tamil also highlighted a host of other Tamil grievances: continued militarisation, the release of private lands and a political solution based on federal model. Yet the organisers chose to lead the meeting with the two demands that would play most controversially with the Sinhalese.

Political observers say this was a thinly veiled attempt to whip up a frenzy of nationalism in the south that could sabotage negotiations on power sharing arrangements to be included in the new constitution. Tamil hardliners who thrive on the politics of division and may even harbour residual separatist dreams, do not favour these negotiations and fear a breakthrough would relegate them to political irrelevance if the power sharing proposals are widely accepted by the Tamil people at a referendum.

In the aftermath of the rally, which continues to create waves in the South, proponents of the demonstration have sought to represent Eluga Tamil as an apolitical democratic mobilisation; an analysis that glosses over the problematic politics practiced by its main organisers who were responsible for mobilising the large crowds present at the meeting two weeks ago.

The critics also take a naive view of the intent of many of the Eluga Tamil organisers, which appears to have been an explicit attempt to antagonise the South and push southern politicians into reassuring their constituencies that they will not concede to Tamil demands on federalism and demilitarisation. The political discourse following the Eluga Tamil event is inflicting grievous harm to the constitution building process that seeks to deliver a final solution on the ethnic conflict. It has provided impetus to rabidly nationalist Sinhalese movements in the South to mobilise support against devolution proposals envisioned for the new constitution.

The rally has also exacerbated fears already prevalent in the Southern polity about granting greater powers for the provinces. Most disturbingly, the event appears to have empowered Tamil nationalists in ways that could create serious political volatility in the North.

Heckling the moderates

Last weekend, at a book launch in Jaffna, a small group of radicals allegedly associated with the Tamil Peoples’ Council Wigneswaran chairs, heckled and disrupted three moderate politicians invited to speak at the event.

TNA MP Sumanthiran, TULF Leader Anandasangaree and NPC Opposition Leader Thavarajah were at the receiving end of the disruptions, for articulating moderate political positions. The same crowds wildly cheered Ponnambalam, Suresh Premachandran and others who also spoke at the launch.

Reports surfaced that attempts to harass Sumanthiran as he was leaving Saraswathy Hall had been foiled by the large crowds surrounding the TNA parliamentarian during his departure. While the radicals were greatly outnumbered at the book launch, the developments raise fears about the security of moderate politicians working in the North, even as nationalist sentiment takes hold in the region.

If the hysteria spirals out of control, it will not be Suresh Premachandran, Gajen Ponnambalam and NPC Member Shivajilingam on whom the volatility will be blamed. By his actions and his support, Chief Minister Wigneswaran has declared himself the spiritual leader of this nationalist movement. And it was of Wigneswaran, that greater things were expected.

It remains unclear how the moderate Supreme Court Judge was co-opted into a dangerous game by Tamil hardliners. But as he spent more and more time in Jaffna, Wigneswaran was brought increasingly under the influence of this groups, even as he actively distanced himself from the moderate TNA leadership. The Chief Minister claimed in an interview with Daily FT last month, that he had become a “native Jaffna man” who no longer sees issues from the perspective of the south.

“You adjust your thought processes according to the people around you,” the Chief Minister said, explaining the TNA leadership’s more conciliatory attitudes towards the Government of the South and the constitution-making process. “If I was in the South, my attitudes may have been the same,” he added.

Divided loyalties

Yet from time to time and especially as he tries to defend himself against a storm of criticism following the rally, the Chief Minister also appears torn about his loyalties and still reluctant to break completely with ITAK and the TNA.

Reports are also surfacing that in light of ITAK opposition and growing southern suspicion for Eluga Tamil and its motivations, the Chief Minister had been expressing reluctance to attend the rally at the last moment. Politicians like Premachandran, whose EPRLF remains a constituent member of the TNA, had been at the forefront of convincing the Chief Minister to attend and make a speech at the event, highly placed sources told Daily FT.

Basking in the glow of large crowds Eluga Tamil managed to mobilise, Premachandran and other Tamil hardliners are convinced that the time is ripe to break with the TNA and strike out as a political alternative to the main Tamil party. Discussions about the timing of this break have already commenced, according to some sources in the North. The Chief Minister’s leadership is of course central to this plan. Without Wigneswaran the group planning to break from the TNA is made up of Tamil politicians whose brand of politics has no popular backing. Both Premachandran and Ponnambalam failed to secure seats at the 2015 Parliamentary election and the Tamil People’s Council made up of Jaffna professionals and academics has no electoral mandate. The Chief Minister, elected in 2013 with a majority of over 100,000 votes, is the only hope for a political future for this nationalist grouping.

So somehow, over the course of nearly two years, the Chief Minister has allowed himself to become a pawn in a game being played by lesser politicians in the Northern Province, whose ideas and politics have proven bankrupt at nearly every election since 2010. Wigneswaran offers this group legitimacy and perhaps even an electoral future. All they offer him in turn is the opportunity to squander his political legacy as the first Chief Minister of the North by driving him towards radical Tamil nationalism and intransigence on the ethnic question.

Saving Wiggie?

So far, Wigneswaran has resisted the calls to break away. True to character, he is likely to mull over that decision for several months more, barring some development in the North or the South that could hasten his choice. As the party contemplates its course of action with regard to its rebellious Chief Minister, it is this reluctance Wigneswaran is showing that could be giving the leadership pause.

In Parliament on Tuesday, even as he maintained the TNA position on the Eluga Tamil rally, Sampanthan defended his Chief Minister, saying his statements were being misrepresented in the press. The continuing tolerance of the Chief Minister and his antics is raising questions in the South about whether the TNA Leader could be using the increasingly hardline Wigneswaran as leverage in his negotiations with Colombo.

But in spite of this discourse, the TNA Leader is unlikely to make sudden decisions with regard to its Chief Minister yet. To begin with, that would be out of character for Sampanthan, party insiders say. The TNA Leader prefers to allow things to take its natural course and while his decisions have not always satisfied everyone in the party, Sampanthan has managed to keep an unwieldy coalition of Tamil parties together against all odds for six years.

For another, perhaps the TNA still believes Wigneswaran is not completely lost and could be brought back to the fold. The Chief Minister’s conduct offers little hope of such a scenario developing, but if there was a chance to reset the clock on his waywardness, that would still be preferable. The Chief Minister’s return to the path of moderate politics would strengthen the TNA’s hand at the negotiating table. It will also relegate bankrupt nationalist politicians riding high in the North today and their southern counterparts, back to the fringes where they belong. In the long term interest of winning the peace for all communities in Sri Lanka, that remains the best possible option. But can the Chief Minister still be saved?