Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Thursday, 24 March 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe has stated that the Government would generate one million jobs and should produce for a “market bigger than the local market,” meaning local production with foreign collaboration and export.

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe has stated that the Government would generate one million jobs and should produce for a “market bigger than the local market,” meaning local production with foreign collaboration and export.

Apparently the PM expects the establishment of a large number of offices, organisations and industries under his policies; mostly by foreigners with local collaboration that will absorb aspiring workers. But does the country have the capability to cater to the demands of these prospective employers?

Unless the country is able to offer skilled manpower at competitive prices, investors would choose another country and the jobs anticipated by the Prime Minister would be only a dream. This article investigates the current skill levels available in the country.

Skill requirements

Skill requirements

The investors’ skill requirements would include construction workers, trainable youngsters for low technology industries, trained technicians for industrial manufacturing and IT skills with English knowledge. In addition, workers should be prepared to learn, respect others and work as a team to reach goals. Do we have a sufficient number of qualified staff with the proper mentality to execute the services planned by the investors?

Enormity of the problem

Currently, practically every sector from plantations, garment factories, Free Trade Zones and every factory, workshop, supermarket and shop experiences a shortage of staff and are hunting for labour. The thousands of advertisements in the Sunday newspapers highlight the enormity of the problem.

Aspirations of people

Today, labourers demand a daily wage of Rs. 1,000 and skilled workers Rs. 2,000 to 3,000 and are in short supply. Over 50,000 unemployed graduates demand State jobs and refuse to work in the private sector. In the irrigations settlements, the families have multiplied, and mechanisation has reduced labour needs, resulting in massive unemployment.

Agricultural authorities have failed to introduce market agriculture, new crops, better utilisation of available water, and reduce wastage, resulting in increased food prices. The question remains; how can our young generation be converted into employable individuals satisfying prospective investors?

Vocational training responsibility

Sri Lanka’s vocational education is executed by number of organisations, under different ministries, but under the overall control of the Ministry of Vocational and Technical Training (MVTT), which introduced the National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) System. The system categorises training into seven levels, 1 to 4 for craftsmen with National certificates, levels 5 and 6 are Diploma level and level 7 is equivalent to a Degree. Several agencies fall under MVTT including UNIVOTEC, DTET, NAITA, and VTA.

UNIVOTEC is expected to conduct Level 7 degree courses for training instructors to teach in Colleges of Technology. However, the commencement of degree courses are delayed due to various reasons.

At present there are 10 Colleges of Technology and 28 Technical Colleges under the Department of Technical Education and Training (DTET), that offer National Certificates and Advanced Diplomas in Engineering, Technician, Engineering Craft and Business Studies, offering NVQ Levels 5 and 6, with a total teaching staff of around 810 and annual training intake of 22,500 students.

The National Apprentice and Industrial Training Authority (NAITA) is responsible for apprenticeship training nationwide. NAITA claims to have 15,000 trainees under its aegis.

The Vocational Training Authority (VTA) offers skills training through a network of training centres. VTA claims to have six National Vocational Training Institutes, 21 District Vocational Training Centres and 238 Rural Vocational Training Centres.

The Tertiary and Vocational Education Commission (TVEC) is responsible for the policy formulation and development of vocational education, also registering all institutions providing vocational training courses and accreditation of training courses. However, even after 10 years TVEC has failed to enforce registration or accreditation.

The 2013 Budget proposed targeting 80% enrolment in secondary education and literacy in computer technology, mathematics, science and English to ensure that 40% enter vocational and technical education, and allocated Rs. 1,600 million to set up 20 Technical Colleges attached to Vocational Technical University Colleges that will accommodate 50,000 Advanced Level students.

The Sri Lanka Institute for Advanced Technological Education (SLIATE) under the Ministry of Higher Education operates 11 Advanced Technological Institutes awarding Higher National Diplomas in fields of Engineering, Quantity Surveying, English and Information Technology. The Cabinet recently allocated Rs. 2,368.5 million to develop 6 institutes.

In addition, Ministries of Education, Skills Development and a host of others conduct training institutions, and the ministers are reluctant to divest their authorities.

Although training centres are plenty, students passing out from these have failed acceptance by the industry, except for the German Training Centre. Most training centres provide low level courses and trainers lack subject knowledge. In recruiting trainers what are the qualification requirements for masonry, three-wheel repairer, hair dresser, pottery maker, etc.? This aspect has been manipulated by politicians to appoint their supporters. Some higher courses are supposed to be in English, but are taught in a mix of Sinhala and English, with notes in English.

Agricultural sector

Agricultural sector

The Sri Lanka School of Agriculture, under the Department of Agriculture, offers two-year Diploma courses in Agriculture at Kundasale, Pelwehera, Angunakolapelessa, Vavuniya and Karapincha in Ratnapura District, a total intake of around 265 students. Kundasale is the only institution offering training in English. Meanwhile, in a newspaper a private organisation offers a six-month course in Tissue Culture.

Private sector

Meanwhile, the private sector offers a wide range of education choices, mostly for affluent students, in the fields of IT, accountancy, business management, engineering and medicine. Sri Lanka has the highest number of British qualified accountants outside of the UK, and considered as a high-value export earner in the IT/BPO sector.

The private sector offers fee-levying courses, mostly targeting foreign universities with first few years in Sri Lanka. Fashion, design and interior décor are newcomers to the field, and hundreds of beauty centres indicate the changing lifestyles and culture capitalised by training centres.

Sinhala Only policy

In 1948, the British left then Ceylon with an efficient State service, health and education system, and infrastructure envied by other Asian countries. Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike elected in 1956, over a Sinhala Only policy, converted education to Sinhala and the Indian teachers employed were asked to leave. The resulting degradation of education standards resulted in British universities refusing acceptance of local university degrees, ending postgraduate training for university lecturers in the UK.

Political problems

In 1970 a coalition of SLFP and left-wing parties formed a new government. The JVP revolt in 1971 left universities closed for over a year, and the shocked Government brought in the Business Acquisition Bill, taking over businesses, industries, lands and housing. The world’s fuel crisis in 1973 resulted in a threefold increase in fuel prices, forcing the Government to introduce austerity measures, including severe import controls, banning import of vehicles; even food and clothing were rationed.

Communal riots in 1983 and the war in the north resulted in most countries boycotting Sri Lanka, and bringing development aid to a halt. The riots and disturbances in 1987/89 resulted in the universities closing regularly, disrupting education. Although by the mid-1990s the backlog of undergraduates was cleared, the quality of the graduates were questionable, but were employed by the State. President Chandrika Kumaratunga managed to end the boycott by foreign countries in the late 1990s. But during the two decades of boycott, the world’s developments in the fields of technology and medicine had bypassed the country.

Exodus of professionals

The country’s internal problems since 1956 and poor employment prospects resulted in successive waves of exodus of professionals. They were welcomed by the West as well as new oil rich countries which amassed wealth and embarked in improving infrastructure as roads, health and education. Nigeria, in particular, absorbed hundreds of engineers, doctors, thousands of technical categories and thousands of teachers capable of teaching in English.

School closures during 1987/’89 saw a proliferation of international schools, whose children were directed towards overseas universities and a high percentage opted to remain outside, resulting in the country losing money as well as educated youth.

Reversal of JVP policy

The Sinhala Only policy converted education from English to Sinhala in schools, and subsequently in universities too. The JVP which became a force in universities acted against speaking in English and even in courses taught in English medium; students were forced to speak only in Sinhala, thereby effectively separating the two communities. This anti-English movement resulted in the graduates in past decades who currently occupy senior positions in the Government service to lack English and IT skills.

After decades of anti-English policy, the JVP in its manifesto prior to the presidential elections 2015 proposed school education in all three languages. But its U-turn on English education policy escaped notice of politicians as well as the public.

Current professional standards

In World University Rankings, none of our universities reached the first 2,000, indicating poor education standards. Our university lecturers, having lost the opportunity of further training in British universities, were sent to Asian universities; however, some had to return due to poor English. Now local universities offer postgraduate courses and lecturers acquire qualifications among themselves. The Kotalawala Defence University, which is yet to function fully, in a newspaper advertisement called for applications for Postgraduate and Doctorate courses.

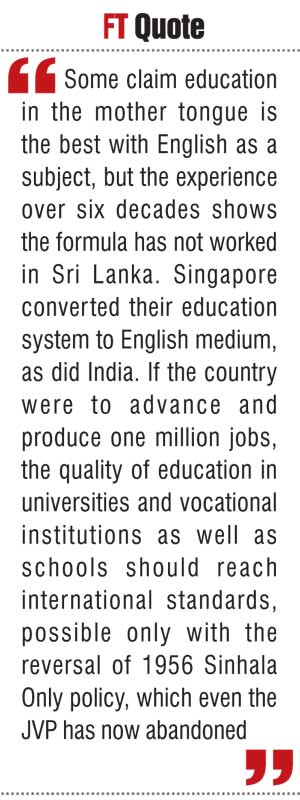

Education system

Some claim education in the mother tongue is the best with English as a subject, but the experience over six decades shows the formula has not worked in Sri Lanka. Singapore converted their education system to English medium, as did India. If the country were to advance and produce one million jobs, the quality of education in universities and vocational institutions as well as schools should reach international standards, possible only with the reversal of 1956 Sinhala Only policy, which even the JVP has now abandoned.

Reintroduction of English

Although an English stream was introduced in schools as far back as in the 1990s, the country failed to convert even a single Teachers’ College to train English medium teachers. Our schools have introduced IT and technology streams; however, without qualified teachers, how can the students advance without English? Even the present Government’s much-boasted education reforms do not anticipate a change into English medium.

German system

In 1985, GTZ (a German Government funded organisation) introduced a dual training system in both India and Sri Lanka, resulting in the German Training School at Ratmalana. India concentrated on developing metal trades, especially in mould making and the use of Computer Numeric Control (CNC) machines, which helped India to become a manufacturing and major equipment exporting country. Unfortunately Sri Lanka did not follow suit.

However, the trained personnel from Ratmalana are held in high esteem by the industry and another German-funded school is under construction in Kilinochchi. But India went further and boasts a large number of training centres and another in collaboration with Volkswagen.

The Government proposes compulsory schooling up to Advanced Level. Meanwhile, in Germany, all companies except very small ones offer apprenticeships; their dual education system has enabled almost half their youngsters to complete an apprenticeship.

Learn from India

India, with 54% of its population below Grade 5, proposes a German type system under ‘Vocational Education and Training Reform in India,’ accessible at https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/publications/publication/did/vocational-education-and-training-reform-in-india/, and gives an indication on how Indians propose to upgrade their skills, would be a lesson to us.

Goals for country’s advance

A. Universities and schools

B. Unemployed graduates

C. Vocational training

D. Commercial agriculture

Enormity of problems affecting improvement

The above shows the enormity of the problem caused by the deficiency of English among lecturers in universities, teachers training colleges, vocational institutions, school teachers and school principals. The vocational trainers need to be experienced persons in technological trades. But the country does not possess even a single institution awarding degree level in the vocational sphere. The current trainers of craftsmen courses also need further training. The question remains, who would undertake the massive task?

The only positive aspect is the large number of training institutions established island-wide with buildings and some training equipment.

Introduction of English

Universities, teachers colleges and vocational institutions need to expand their English departments massively by employing more teachers. Vocational centres need teachers with vocational knowledge.

A/Level science classes are taught by graduates who studied in English medium, as such they could teach science subjects in English, but during the initial months their quality would be inadequate. School teachers need to upgrade their English skills and the teachers reaching required standard in IELTS could be allowed to teach in English medium and given an allowance. Teachers could follow private classes or follow English courses available on the internet.

The British Council, which already conducts English classes but is limited to a few locations, could be requested to expand its services. However, taking the training to provinces would require private sector and possibly Indian teachers.

Upgrading vocational training

The German Training Centre’s capacity is limited and the country should request training centres for every province and a higher training institute from Germany. Our President missed a golden opportunity when he visited Germany; he should have requested Germans for additional schools.

The high-scoring graduates from provincial training centres and graduates from universities could be admitted to the advanced vocational courses. The resulting graduates could become lecturers in vocational institutions and others would be grabbed by the private sector.

Past follies

The politicians noted the damage done by the Sinhala Only policy and the 1978 Constitution introduced English as a link language, but none took further action. During the late 1990s an English stream was introduced, but still not a single Teachers’ College was converted to train English medium teachers. Meanwhile, over 200 teachers were further trained in India. What happened to them?

The JVP Policy Statement in 2014 proposed education options in all three languages, but the current Education Minister seems to be blind to the fact. The country is paying for decades of neglect.

Implementation

The progress of transformation to English would depend on the number of lecturers/teachers and the availability of training centres in the locality. The country would require thousands of teachers capable of teaching in English, but are not available. Meanwhile, Sinhala medium students continue demanding non-existing State jobs, and 200,000 students complete their A/Levels annually, and expect places in universities or other training.

While vocational training schools may be established with German assistance, they would require assistants. In addition, the trainers of craftsmen categories should be vocationally competent.

Getting a large number of English and vocational teachers would be no easy task. Only option would be Indian teachers, who are the only country capable of supplying our requirement.

ETCA to the rescue

Universities accommodate only 10% of AL students; the balance and O/L dropouts need to be guided to employment. During the past, Arts graduates were accommodated in the Government service, an option which is no longer available. Thus the Government has no option but carry out education reforms to produce a workforce acceptable to prospective investors.

Getting the large number of experienced lecturers, teachers and vocational teachers would be possible only from India and needs to be negotiated with the Indian Government, who may agree to bear the cost as a loan. For upgrading Teachers’ Colleges and vocational institutions, lecturers could be trained locally by Indian trainers, in specialised institutions, while a select few could be sent to Indian Training Institutions.

The speed of transformation to English and improvement in vocational education would depend on the number of teachers India could release. Also the allocation of places in Indian Training Colleges to train our staff.

The current ETCA agreement under discussion with India could include the supply of Indian Professionals in the education and vocational sectors. In addition, Indians could be invited to establish training centres in English and Vocational sectors competing with the government and private sector, will help to improve quality and bring down the charges to an affordable level for students.

The Government is continuing to spend large sums of money on buildings and staff of vocational training institutes, while neglecting teaching quality, resulting in an unemployable disgusted youth. Meanwhile, private investors cry for trained staff. If the present Government neglects to carry out the actions highlighted above, the PM’s boast of one million jobs will remain a dream and the country would face another revolt from the unemployed youth.

(The writer is a Chartered Civil Engineer graduated from Peradeniya University and has been employed in Sri Lanka and abroad. He was General Manager of State Engineering Corporation of Sri Lanka. He can be contacted on [email protected].)