Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Monday, 16 May 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Central Bank’s response is a salutary development

Central Bank’s response is a salutary development

A response issued by the Central Bank (available at: http://www.ft.lk/article/540589/Central-Bank-has-its-say-over--Continuously-loss-making-Central-Bank-is-no-better-than-Sri-Lankan-Airlines- ) to an article published by this writer in this series (available at:  http://www.ft.lk/article/539287/Continuously-loss-making-Central-Bank-is-no-better-than-SriLankan-Airlines ) drawing the attention of the top political leaders and the members of the public to continuing losses in the Central Bank has been carried by Daily FT in its edition on May 9, 2016. This is a salutary development and should be promoted by all means. That is because it paves the way for the public to have a productive discussion on the subject and help the government to map out strategies to be adopted to avert a potential crisis in the future. In an economic democracy which this government has committed itself to establish in the country, such intellectual debates are a sine qua non.

http://www.ft.lk/article/539287/Continuously-loss-making-Central-Bank-is-no-better-than-SriLankan-Airlines ) drawing the attention of the top political leaders and the members of the public to continuing losses in the Central Bank has been carried by Daily FT in its edition on May 9, 2016. This is a salutary development and should be promoted by all means. That is because it paves the way for the public to have a productive discussion on the subject and help the government to map out strategies to be adopted to avert a potential crisis in the future. In an economic democracy which this government has committed itself to establish in the country, such intellectual debates are a sine qua non.

Rule of a civilised debate: Honour the opponent

However, it is also essential that such debates and disputations are conducted, as Emperor Asoka had pronounced in one of his rock inscriptions some 24 centuries ago, ‘by duly honouring the opponents in every way on all occasions’. This writer wrote several articles on the question of the central bank incurring losses, making profit transfers to the government when it had made losses and the depletion of the capital base of the bank over the time to critically low levels. These issues were raised with the Monetary Board of the Central Bank since it is the Board which is ultimately responsible for the successes or failures of the institution known as the Central Bank. Since the Board is made up of professionals of high standing, this writer sees no problem in observing the wisdom promulgated by Emperor Asoka when conducting this debate.

CB’s response is presumed to be a response of the Monetary Board

It is not clear whether the response in question had had the sanction of the Monetary Board since it begins with the qualification that ‘the attention of the Central Bank has been drawn’ to an article written by this writer who has been correctly identified as ‘a retired employee of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka’. However, a Monetary Board which is aware of its powers and responsibilities cannot be expected to allow its operational arm to issue responses on its behalf without first screening them. Hence, it is presumed that the response carried by Daily FT is a response issued by the Monetary Board.

Central banks should not make continuous losses and eat up capital

The Board has reiterated in its response the argument which it had made earlier with respect to profit-making by a central bank. That is, a central bank is not considered a profit-oriented institution in any economy implying that Sri Lanka’s central bank too should not be judged on the basis of the level of profits it makes. There is no dispute over this stand of the Monetary Board as this writer too in his previous articles in this series had expressed the same opinion. This is not the issue raised by this writer in the four articles published in this series. These articles in fact raised three issues in three different stages. The first one related to the making of a profit transfer to the government by the Board in 2013 when the Bank had in fact made losses. The second one was incurring a loss for a second year in 2014 and transferring profits to the government, while causing a depletion of the capital base of the Bank. This writer pointed out that reducing the capital to a low level of 25% of the Bank’s domestic assets portended an ominous development which the Board should not take casually. The warning given here was that if it continued, the government and therefore the citizens have to pump money to the Central Bank to build its capital. The third one was about a further depletion of capital to 18% of its domestic assets due to continued loss-making by the Board for a third year in succession in 2015. Given the political, financial, and budgetary calamity that it has created, this writer suggested that the Board should introduce a restructuring plan immediately to reverse the ominous trend. If this message was not clearly understood by the Board, it is not a fault of the Board. Rather, it reflects a deficiency on the part of this writer in presenting his arguments in a manner that could be understood by readers.

A central bank with a depleted capital is like the bankrupt national carrier

The Board has opined that this writer may have equated the loss making central bank to the bankrupt national carrier – Sri Lankan Airlines – to sensationalise his story. That is not a correct reading of this writer’s comparison. The comparison was made to drive home the point that the continuously loss making central bank had had a rapid depletion of capital to a very critical level and if corrective measures are not taken early, like the Sri Lankan Airlines, the government would have to pump money to recapitalise the bank at great costs. This would not be an easy task for the government since it did not have money even to pay interest on and repay the principal of its debt.

Not many options for rescuing a bankrupt central bank

But this writer agrees with the Board that the comparison of the central bank with the Sri Lankan Airlines maybe unfair on some other ground. That is with respect to the number of options available for bailing out the two institutions concerned. In the case of the Sri Lankan Airlines, the options are many – like selling of aircraft, handing over the management to outsiders or even an outright sale of the airline to a competent party – other than providing capital from by the government. None of these options are available when a bankrupt central bank is being bailed out. The only option available is the provision of funds by the government or by some outside parties as was the case with the bankrupt Central Bank of the Philippines in 1993. In this latter case, it was the US government, the government of Japan and IMF that provided funding as a loan to set up a new central bank in that country to the much embarrassment of the Filipino authorities (available at: http://www.ft.lk/article/222078/Even-mighty-central-banks-can-go-broke-if-imprudent-policies-are-adopted ). In this background, the Monetary Board which advises the government on good economic policy cannot remain a passive spectator when the central bank’s capital funds are fast declining due to continued losses, irresponsible profit transfers and profligate expenditure programs.

Common sense is better than irrelevant authoritative opinions

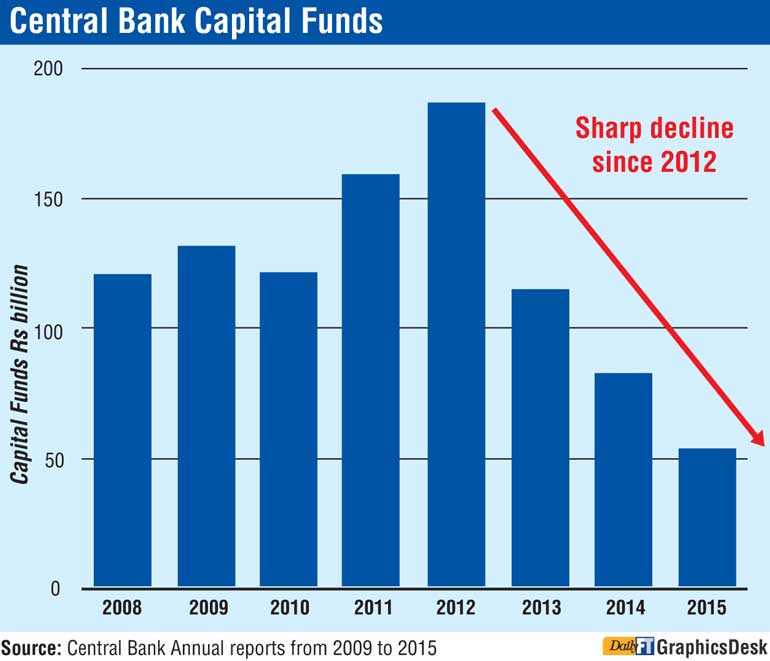

The Board has been ‘surprised’ by this writer’s ‘flippant dismissal’ of the contributions by world renowned authorities on central banking and has justified its continued reliance on their wisdom to go for a negative net worth in the central bank. Academic work certainly helps one to understand problems provided such work is relevant to the case in point. This writer’s argument was that the advice given by these world renowned authorities was relevant only to a country which had a space for spending freely. Such a country can, without making an unbearable sacrifice, allocate funds to provide capital to a bankrupt central bank. Sri Lanka’s case was different, this writer argued. Its government cannot pay even the salaries of public servants and service its debt. Hence, it was inadvisable, this writer warned the Board, to rely on such academic work and watch over impassively the conversion of the net worth of the bank from positive to negative. Besides, what matters for risk management is not the findings of academic work but the common sense of the people who are to manage the risks. That is why this writer advised the Board to take notice of the fast declining capital base of the Central Bank and make amends immediately to reverse the trend. The graph shows how the capital base of the central bank has been falling sharply since 2013.

Judge an institution not by action but by outcome

The Board has provided a long list of work it has done to improve the risk management in the central bank. That may be true. But the Board, as the top most economic advisor of the country, should know that public policies are assessed today not in terms of inputs or outputs; rather they are assessed in terms of the results and outcomes. Even after the Board has introduced improved risk management policies, the depletion of the capital base of the central bank could not be halted by the Board. It in fact fell, according to the audited accounts of the central bank as reported in its Annual Report for 2015, from Rs 82 billion as at the beginning of 2015 to Rs 54 billion by the end of the year. This shows that there is a clear case for the Board to reassess its present risk management policy strategies. This is where it has to use its common sense departing from relying on academic work which will not rescue it when the central bank needs capital infusion by the government.

Will the Board permit a bank with a declining capital base to continue?

A person with common sense would ask two simple questions from himself in order to assess the gravity of the risk he is facing. The first question: What does he think of an institution whose capital is depleting continuously? The second question: How does he rate an institution which has refused or failed to take corrective action to arrest the situation? Both these questions are relevant to the Monetary Board as the regulator of financial institutions. How would the Board look at a bank that is continuously experiencing capital depletion and failing to take any corrective action? Will it accept the stand taken by the bank that academic work has suggested that capital depletion is not a problem since it can always recapitalise itself by going to the capital market? This is where one has to draw the line between the academic work of renowned authorities and the common sense of ordinary people.

Dispute over the losses in terms of MLA

The Board, in its response, has elaborated on the disclosure it has made in the financial statement of the Bank for 2015 in Note No 30. The particular note has converted the losses reported in the income statement of the Bank to a format reflecting how they should be calculated as per the Monetary Law Act or MLA. For the education of the ordinary readers who have no familiarity with accounting systems, this is what the Board has done. It has started from the loss of the Bank amounting to Rs 19.7 billion as given in the income statement or the profit and loss account of the central bank, calculated in terms of the international accounting standards now known as International Financial Reporting Standards or IFRS. These losses have been lowered or increased by certain items which have to be reckoned under IFRS but not under the provisions of MLA. Hence, Note 30 is simply a reconciliation statement to arrive at the distributable profits in terms of MLA which in this case is a non-distributable loss of Rs 36 billion. This is the figure disclosed in the financial statements, audited by the international auditors and as approved by the Auditor General. But in the response in question, the Board has come up with a figure of Rs 4.7 billion which it says the profits the bank made in 2015 in terms of MLA. In arriving at this figure, what it has done is another reconciliation in which IFRS losses have been increased by the gain in the value of external assets due to exchange rate depreciation but removed from the losses a sum of Rs 34.9 billion which is already charged to the income statement as an expenditure incurred on account of the losses in foreign assets due to marking them to their market value. The Board believes that this is not an expenditure item permissible under MLA and, therefore, has taken out from the losses to show a profit of Rs 4.7 billion under MLA in a table introduced for the first time in its response.

Mark to market losses should also be charged to revenue

This interpretation by the Board is erroneous. MLA has not specified how the profits or losses should be calculated by the bank and had expected the bank to follow the prevailing best practices in accounting. The only exception has been its provision with regard to the treatment of gains or losses in foreign assets on account of changes in the exchange rate. Why this has been taken out from the profits is to prevent the government from grabbing funds from the central bank by deliberately devaluing the external value of the rupee. For instance, if these gains are treated as distributable profits, the government can deliberately devalue or in the present case, depreciate the rupee, show profits and grab that non-earned money for government expenditure programmes. Hence, as John Exter has explained it (p 23 of Exter Report), MLA has forced the central bank to sterilise them. But, mark to market losses are outside the control of the government or the Monetary Board and therefore, in sound accounting practices, they should be charged to the current income thereby reducing the distributable profits of a business. This rule applies to the central bank too and it is a rule which the central bank insists that all financial institutions too should follow. The reverse involving mark to market gains is treated differently: They are not added to the current income, but recognised and transferred to the reserves directly. Hence, the principle pronounced in MLA is clear. What is within the control of the government should not be treated as profits but what is outside its control should be included as an expenditure. Hence, Note 30 in the financial statements, audited by auditors, is in line with MLA, but the table given in the response is not. The Board has made a wise decision not to publish this spurious table as a part of its financial statements. Had it been done, Board members and the officers or auditors of the bank would have been guilty of an offence involving the submission of false information to the Minister, in terms of section 46 of MLA. Contrary to the Board’s claim that it has made profits in 2015, central bank’s net worth, that depicts the losses it has made during the year, has fallen by Rs 28 billion from Rs 82 billion at end-2014 to Rs 54 billion at end-2015.

See the bigger danger of declining capital of central bank

What should concern all the stakeholders of the central bank is not the profits per se. Profits can be manipulated or abused by concerned parties to attain their own objectives. Hence, as this writer has argued in a previous article, what matters to the Board is the decline in the net worth of the bank (available at: http://www.ft.lk/article/424477/The-issue-of-continual-losses-and-depleted-capital--Central-Bank-still-misses-the-main-point ). This is in accord with the elementary principles of accounting where profits or losses are gauged by considering the change in the net worth of an institution and not by looking at the figures given in the income statement per se. This common sense is taught by accounting teachers to students who begin learning the subject as outlined in the story presented by this writer in the article referred to in this section.

In this connection, as the graph shows, the net worth of the central bank is falling fast and the Monetary Board, in its wisdom, should not watch over it impassively.

W.A Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected]