Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday, 11 July 2024 00:45 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Labour landslide

France’s victorious Melenchon and comrades

The Old Guard, last week

Revaluating R. Sampanthan

“This result [the French Left’s win], as well as the victory of the Labour party in the United Kingdom, reinforces the importance of dialogue between progressive segments in defence of democracy and social justice. They should serve as an inspiration for South America.”

– Brazil’s President Lula da Silva –

Britain’s centre-left Labour party swept the Parliamentary election while France’s unified Left, the New Popular Front, unexpectedly beat both the Far Right and Macron’s neoliberal centrists to win the National Assembly election, becoming the largest formation.

Britain’s centre-left Labour party swept the Parliamentary election while France’s unified Left, the New Popular Front, unexpectedly beat both the Far Right and Macron’s neoliberal centrists to win the National Assembly election, becoming the largest formation.

Dr. Masoud Pezeshkian, the reformist candidate who criticized the ‘morality police’ and promised a relaxation of headscarf rules won 53%, beating his religious conservative opponent to be elected Iran’s new President.

Will Sri Lanka’s parochial politicians will learn the lessons?

Significance for SJB

Sajith Premadasa, Dullas Alahapperuma and Prof Charitha Herath were the first local politicians to X congratulations to Labour’s Keir Starmer. (https://x.com/DullasOfficial/status/1809144512998195510?t=2ybKPeKP03o_MXNykhvRFQ&s=08); (https://x.com/charith9/status/1809619507419468036)

Sajith is a soi-disant social democrat. Dullas and Charitha are center-leftists of long-standing. All are Oppositionists.

The gesture was interesting. Ranil Wickremesinghe officially hooked-up the UNP with the global Right/Centre-Right, the International Democratic Union (IDU) co-founded by the UK Conservatives and the US Republicans in 1997. The breakaway SJB never broke from the IDU and the UK Conservatives; never hooked-up with the US Democrats or UK Labour. Second only to Ranil and his crew (including his SLPP cubs), the SJB’s Economic Council and its Economic Blueprint are the closest you get in Sri Lanka to the economic ideology of the crushed Conservatives.

Harsha de Silva’s Gampaha speech (July 7th) proved he had learned absolutely nothing from the UK Conservatives’ debacle, except to double-down on the same rancid doctrine of free-market neoliberal globalism.

The UK election was a backlash against the Conservatives’ economics of cutting public spending and relying on privatization, which had led to the crisis of public services from British Rail to the NHS. The unified Left’s win in France was explicitly against both Macron’s technocratic neoliberalisme and the ultranationalist, xenophobic Far Right.

The SJB’s neoliberal twins Harsha and Eran articulate an ultra-reactionary economic delusion – a dystopia to most of us--which can be summarised as “we are the real UNP, actual descendants of the UNP’s father-figures, and when we win we shall catch-up by pushing through all the painful decisions and bitter medicine the UNP couldn’t, starting with BR Chenoy 1965 and including the Motorola deal 1980.”

The SJB Economic Council should grasp that even if Sajith were to win the Presidency in a close-run race, its post-election economic fantasy will be caught in a pincer, resisted and countervailed by the strongest Lankan Left of our lifetimes: Anura Dissanayaka’s NPP in Parliament –if he fails to win the presidency, he may be elected PM-- and Wasantha Mudalige’s PSA outside.

|

Sajith salutes Starmer

|

NPP-SJB dynamic equilibrium

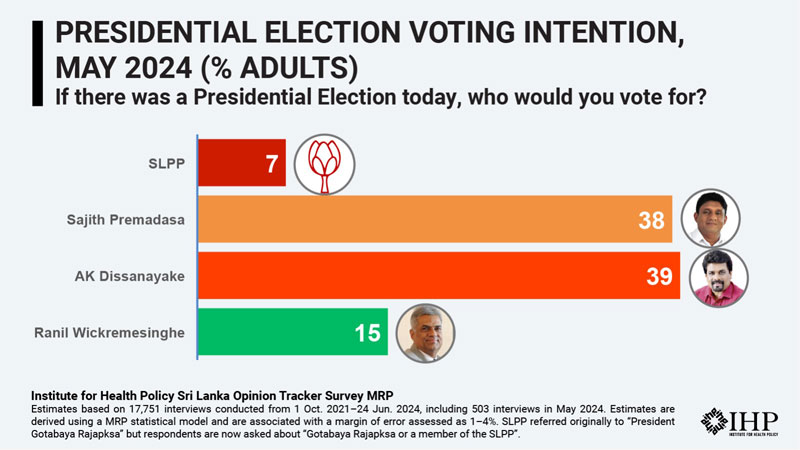

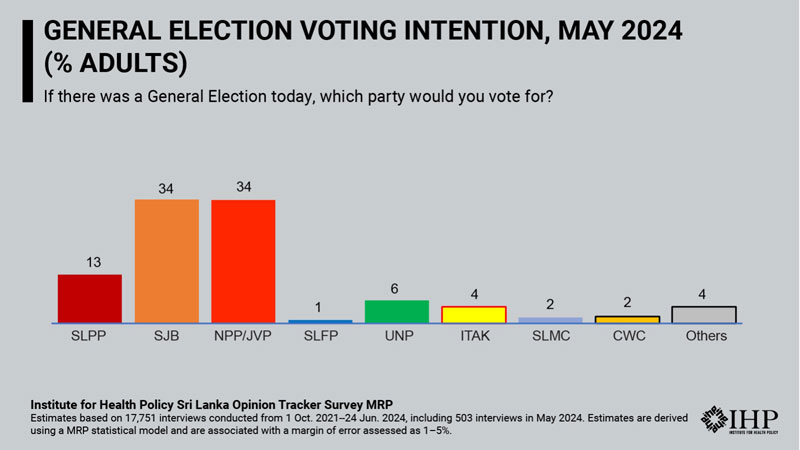

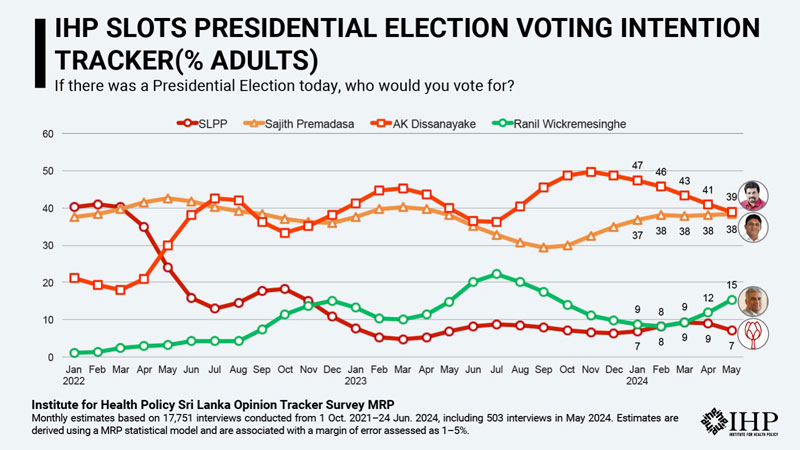

The latest data released by Dr. Ravi Ranan-Eliya’s IHP, the most regular and consistent public opinion polling available in the public domain should come as no surprise. What the results reveal is that:

The gap is closing or has closed between the front-runners, Anura and Sajith.

The gap is closing or has closed between the front-runners, Anura and Sajith.

Incumbent President Wickremesinghe, though improving his performance, reveals no realistic mathematical probability of winning.

Incumbent President Wickremesinghe, though improving his performance, reveals no realistic mathematical probability of winning.

The tripolar Presidential contestation will increasingly polarize into a bipolar one which is settling for the moment into a ‘rough equivalence’ or ‘essential equilibrium’ between Anura/NPP and Sajith/SJB.

The tripolar Presidential contestation will increasingly polarize into a bipolar one which is settling for the moment into a ‘rough equivalence’ or ‘essential equilibrium’ between Anura/NPP and Sajith/SJB.

Sajith and Anura have to win over the uncommitted ‘swing’ voters who will decide the Presidential election. This means:

i.Sajith/SJB has to shift to Starmer/UK Labour’s moderate social democracy by strategic partnership with the Dullas-Charitha faction.

ii.Anura/JVP-NPP has to achieve hegemony by occupying the intellectual-moral-ethical-cultural high ground (Gramsci) and producing a first-rate economic policy platform as did UK Labour and France’s New Popular Front.

Anura by a whisker?

NPP-SJB dead heat

Electoral equilibrium

JVP-NPP’s risky exceptionalism

There was no message (that I saw) from the JVP-NPP, or simply the NPP, congratulating Starmer, the man from a blue-collar background and a red-brick university, for his victory over the arrogant Conservative establishment. Labour campaigned on the theme of “Change” and the slogan of the “renewal” of the country. Close enough and useful enough for the NPP, but there was no audible applause.

Perhaps it is because neither the JVP nor its broader political movement the NPP embraces the identity of ‘Centre-Left’ which Labour is emblematic of. The JVP-NPP does not even endorse Social Democracy. It itself sees itself as ‘Left’, or ‘Left populist’ but that merely camouflages the strategic problem.

The JVP’s leftism has always been ‘exceptionalist’, rather than one of creative adaptation or synthesis of international ‘best practices’. Today that ‘exceptionalism’ is clear, when contrasted with the Left in France and Latin America.

In France, the 1936 Popular Front has been reborn as the New Popular Front, a coalition of four left parties with the most prominent leader being Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Brazil’s Lula returned to the Presidency on a 10-party platform. Mexico’s Dr. Claudia Sheinbaum, among the founder-leaders of Lopez Obrador’s left-populist movement Morena ran on a three-party platform which included Morena.

The JVP-NPP has not positioned itself strategically in any one of the three main global modes/archetypes of post-Cold War left success:

(a) Centre-Left (UK, Australia).

(b) Left Front (France, Kerala, Nepal).

(c) Left-Populist Front (Latin America).

Its academic ideologues insist that the NPP is ‘Left populist’ but that approximate resemblance is discursive, not substantive or strategic. Since Uruguay’s Frente Amplio (1971 to date), left-populist success in Latin America has always manifested itself as a broad pluri-party project, i.e., an extended Popular Front on Gramscian/neo-Gramscian lines.

As the quote on top of this page proves, Brazil’s President Lula, the father of the Pink Left, sees the experiences of France’s New Popular Front, UK Labour and Latin America’s Left as linked, almost a triangle. AKD-JVP-NPP should be somewhere within this triangle, but sadly isn’t—so far. The formation should reposition itself.

Someday soon, the JVP-NPP and the FSP-PSA will have to learn from France, Nepal and Latin America that a united Left Front is a political and electoral imperative. Anura-Vijitha-Pubudu synergy could cause a political ‘quantum leap’. Unity multiplies, not just adds.

Meanwhile, Sri Lanka’s Communists (CPSL) inhabiting Sarvajana Balaya is as if the French Communists (PCF) allied with Le Pen’s ‘National Rally’ rather than co-founded the leftist New Popular Front.

R. Sampanthan’s tragic failure

My fond esteem for Hon Sampanthan, my late father’s friend who had been published several times in the Lanka Guardian magazine, was such that when we were actively on opposite sides of the barricades and I was Sri Lanka’s Ambassador/Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Geneva, my wife Sanja and I hosted him for dinner when he was in town to lobby votes against Sri Lanka at the UN Human Rights Council.

The big question about Sampanthan, who always stood for a united, indivisible Sri Lanka, is not why the Tamil Question could not be solved in his lifetime, but rather, why it couldn’t be solved in that part of his lifetime which was postwar. With Prabhakaran alive, any deviation on Mr. Sampanthan’s part would have meant assassination. But what about post-Prabhakaran?

With the end of the war there were two ways for the Tamil politics to go. One was to work towards a political solution to address the root causes of the war, beginning with what was left standing in the rubble of the war, i.e., the 13th amendment. The other was to go after the Sri Lankan state on issues of accountability as a resentful lashing-out having lost the war.

Accountability is a valid concern and legitimate demand. I am not arguing that accountability and autonomy shouldn’t be sought together. I am arguing that any attempt at doing both simultaneously becomes a tangled knot because they entail two different coalitions of support.

Northern Ireland’s Good Friday agreement did not include accountability. It succeeded. Usually, political reforms are possible but accountability is traded-in or deferred by decades. Political democratization moved rapidly in post-Franco Spain, but accountability for the Civil War of the 1930s is still moving slowly.

Even if accountability and autonomy were to be demanded together, they need downsizing to fit into a package which is politically viable, i.e., acceptable to the majority of voters and sufficiently safe for supportive political parties.

This is not the route that Sampanthan went. Instead, he sought to make two ambitious moves together:

Going beyond the 13th amendment and even the unitary state itself, in striving for political autonomy.

Going beyond the 13th amendment and even the unitary state itself, in striving for political autonomy.

Going beyond the national judicial process and system in striving for accountability.

Going beyond the national judicial process and system in striving for accountability.

He sought post-unitary/non-unitary autonomy, and a judicial process which was international. The outcome was the failure to achieve either enhanced autonomy or effective accountability.

Mr. Sampanthan lacked historical realism. While he never made a speech without a strong dose of ‘historicism’, by which I mean the long litany of broken promises made by successive Sinhala political leaderships, his historical narrative tended to be one-sided. It did not include the lapse of the ITAK led by Mr. Sampanthan when Sri Lanka had the most liberal, anti-chauvinist political dispensation of President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, and the most generous Constitutional offer on the table. I refer to the draft Constitution presented to Parliament in August 2000. I was at Lakshman Kadirgamar’s home at his invitation when he returned from Parliament, heartbroken. He had an assurance of support for the new draft Constitution from his friend Sampanthan, but at crunch-time, the TULF leader reneged. Sampanthan was simultaneously ‘historicist’ and ‘a-historical’. There was no way that a side –secessionist Tamil nationalism--that chose to resume a civil war when there had been a succession of openings for a negotiated settlement, could obtain in defeat what it could not at the zenith of its military trajectory.

The TNA which had openly proclaimed the LTTE as the sole legitimate representatives of the Tamil people, thus tainted in the eyes of the majority of the island’s voters, could not push beyond what had been obtained for the Tamils by India. Mr. Sampanthan had not played John Hume.

It was a-historical not to understand that a long, intense civil war had been fought and lost, and that it would be a struggle to retain what was already in the Constitution. The failure to actually accept the historical moment he was living in, that of decisive defeat of a project in a protracted war, and the resultant reality that the only viable strategy was a defensive one, lay at the root of Mr. Sampanthan’s political failure.

This a-historicism was also responsible for failure on the accountability front. Instead of rejecting the Lessons Learnt report, Mr. Sampanthan should have insisted on its implementation.

Mr. Sampanthan refused—except in the very last years of his life, when it was too late—to accept the 13th amendment as the basis and framework of a political solution. For the most part of his political life he rejected a priori, any political solution to the Tamil Question within a unitary form of state.

He continued to advocate the re-merger of the Northern and Eastern provinces as currently constituted—which no political party or leadership, including Anura/NPP and Sajith/SJB would champion.

Mr. Sampanthan not only failed to make the correct choices at the correct time, he made the wrong ones. In 2015-2019, he robustly supported Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe in a two-track road to political disaster: the 2015 Geneva UNHRC resolution which called for hybrid courts with foreign judges, and the non-unitary new draft Constitution. Either would have capsized the Yahapalanaya Government, both were bound to, and did, decimating the UNP. Ironically, Mahinda Rajapaksa unblocked the Northern Provincial Council and held an election to it in 2013, while Ranil Wickremesinghe as PM placed the entire system of Provincial Councils (PCs) in a prolonged coma by his pseudo-reformist injection (2015) into the PC electoral arrangements.

Sampanthan had one real chance of successfully resolving the Tamil issue and ending his life with a victory. That was in 2011-2013, when negotiating with President Mahinda Rajapaksa.

That failed because he eschewed the path of taking the 13th amendment as baseline, pushing instead for a revision of the provisions of 13A regarding land which had been carefully negotiated between India and Sri Lanka. Coming two years after a military defeat in a war between two belligerents whom he had hardly hovered above or been nonaligned between, the push on the hyper-sensitive subject of land enabled the Sinhala hawks in the Rajapaksa administration to lobby President Mahinda Rajapaksa to suspend talks.

Mr. Sampanthan should have lobbied Delhi in the immediate aftermath of the war, to persuade Colombo to make good on President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s promises on the 13th amendment and to address accountability questions. Instead, he delayed, and then greatly overshot the mark.

In 2013, President Mahinda Rajapaksa invited me to attend the swearing-in ceremony of former Supreme Court judge CV Wigneswaran as the Chief Minister of the Northern Provincial Council. We stayed for a sit-down lunch and posed for an official photograph on the steps. I had finished my stint as Ambassador in Paris and to UNESCO. I guess I was there because of my consistent support for devolution (even at the cost of my post in Geneva despite success at the 2009 UNHRC vote) and my status as a former Minister of the first Northern and Eastern Provincial Council in the wake of the Indo-Lanka Accord.

The new Chief Minister left early and immediately issued a statement calling for “internal self-determination” which made the entire exercise a non-starter. TNA leader Sampanthan and parliamentarian MA Sumanthiran stayed on for lunch. The TNA duo gave me to understand that they expected MR to appoint me the new Governor of the Northern Province, once General Chandrasiri ended his term as Governor and as part of the ‘demilitarization of political and civil administration’ that MR had agreed to with the Indian High Commissioner.

Laughingly I told the TNA leaders that any expectations of my appointment would amount to nothing. They replied, “but who else is there, who would be better? You’d be the most suitable…” to which I replied, “you’re probably right, but that’s why it won’t happen”.

Fairly shortly after Mahinda Rajapaksa had held elections to the Northern Provincial Council and sworn in Wigneswaran as Chief Minister, there was an aggressively hostile, LTTE-flag-waving demonstration against him while on a visit to Britain. Devananda’s EPDP apart, no moderate Tamil faction in the UK or Sri Lanka opposed or criticized it. Secretary/Defence Gotabaya successfully used the opportunity to persuade MR to extend his old Army buddy General Chandrasiri’s Governorship for another term.

At Wigneswaran’s 2013 swearing-in I asked Messrs. Sampanthan and Sumanthiran about Sinn Fein, the Good Friday Agreement, and shared what Martin McGuinness had explained to me years before (after I had interviewed him on TV in Colombo) about the Provisional IRA’s changed calculus and consequent positional pivot. I posed Mr. Sampanthan a question: “Why is it that what is adequate for the Catholics of Northern Ireland, is insufficient for the Tamils of Northern Sri Lanka?” I never received an answer.