Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Friday, 26 January 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Ryan Holsinger and

By Ryan Holsinger and

Natalie Soysa

In 1901 Ceylon was firmly in the grip of the British Empire. Some might even say – comfortably so. For, unlike over the Palk Straight in India, where the colonial government was dealing with an increasingly violent rejection of their rule, here on the little island, the resistance had all but snuffed itself out. The elite of the country had settled down into a cosy and lucrative co-existence with their masters, while English language and culture dominated the social scene.

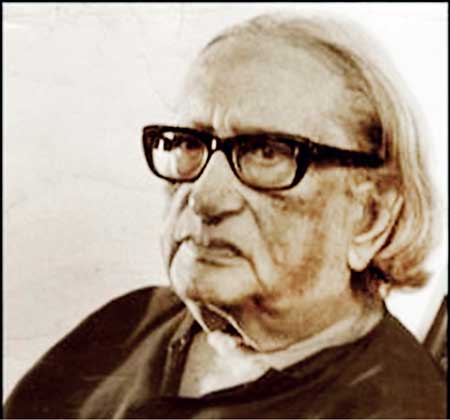

So it was when George Percival Henry Keyt was born on 17 April 1901. His parents – Henry and Constance were of gentile Dutch Burgher heritage and firmly embedded in the upper crust of Ceylonese society. They lived in Kandy. Like their peers they spoke English at home, professed the Christian faith, embraced Victorian style and sent their children to English missionary schools. When it was time for George to go to school, Trinity College Kandy would have been an obvious choice.

George might not have been alone in being bored and frustrated with school, but at the age of 16 when he flatly refused to attend; the rebel in him had already sprung. This is not to say that George was uninterested in learning. He would remain a lifelong student. The young Keyt was, in fact, a voracious reader and perhaps recognising the fact, the famous Rev. Fraser allowed him the use of the Trinity College Library long after he ceased to be a student of the school.

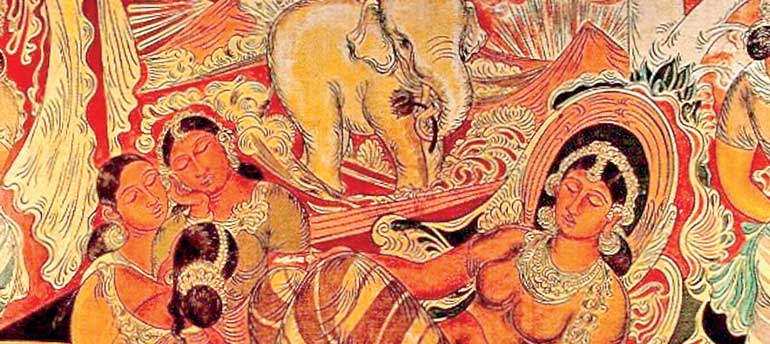

By the time he was 20, his mind was already a vast repository of knowledge and his skill at drawing was beyond doubt. But circumstances would conspire to set his life upon a different course. Living in the neighbourhood of the Malwatte Viharaya, it was inevitable that he would stumble upon the world of Buddhist philosophy and art. The results of that encounter are plain to see right throughout his life. He was captivated by the Buddhist monk and scholar – the Ven. Pinnawela Dhirananda who opened his eyes to the art, literature and history of Sri Lanka. The temple paintings, the countryside, the people, all came to inspire him and leave an indelible mark on his work.

He translated several ancient Sinhala and Pali texts, was published frequently in the Buddhist Annual of Ceylon and wrote extensively on art, customs and Buddhist philosophy. He embraced the Buddhist way of life and was an advocate of the Sinhala Nationalist cause. His talents and his interests could have steered him in any number of directions, but by the time he was 26, it was clear to him and to those around him that painting was his calling in life. And so burst forth the artist who played no small part in dragging Sri Lankan art out of the Middle Ages.

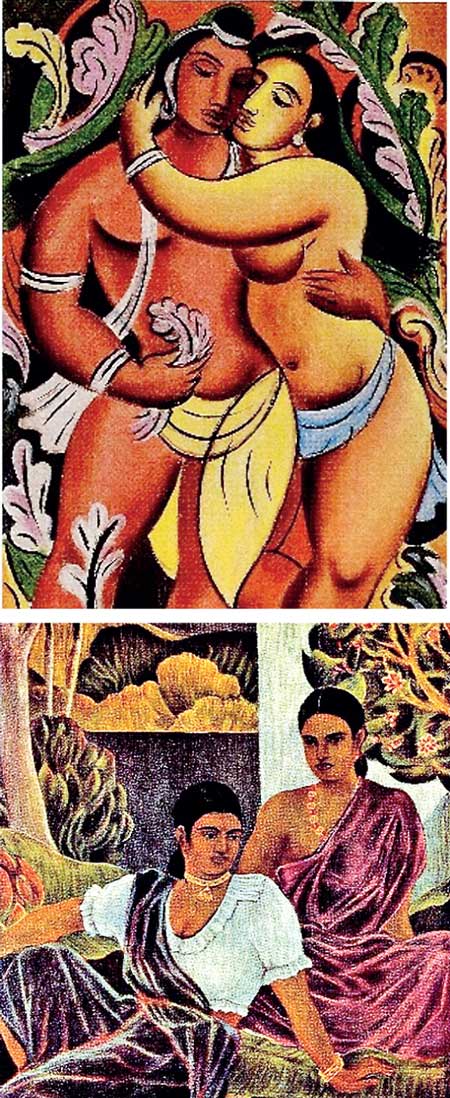

When George Keyt’s career as a painter was taking off he was not often compared with other local artists, but rather with his great contemporaries – Matisse, Braque, Picasso and sometimes Gauguin. He did in fact employ a range of techniques that were similar, but no more so than these great masters had themselves taken inspiration from Renoir, Van Gough and Cezanne. What he really emulated was their propensity to push the boundaries of art. Throughout the 1930s George was crafting his unique style of cubism into something tangibly Sri Lankan. His subjects were often ordinary local folk. In his compositions you’d regularly find his own surroundings. But as works of art, his paintings were admired around the world.

The Nobel Prize winning poet Pablo Neruda was in Sri Lanka as the Consul for his country in 1929/30. He put it most eloquently when he declared: “Keyt, I think is the living nucleus of a great painter. Magically though he places his colours, and carefully though he distributes his plastic volumes, Keyt’s pictures never-the-less produce a dramatic effect particularly in his painting of Sinhalese people. These figures take on a strange expressive grandeur and radiate an aura of intensely profound feelings.”

The famous art critic Dr. Klaus Fischer said “…when abstracting more and more from naturalistic form he is following ancient artistic ideas of East and West.; the fact that he applies techniques developed in the West shows him to be a citizen of the modern world.”

George Keyt married Gladys Ruth Jansz in 1930. They had two daughters whom he was devoted to, but their marriage didn’t last the decade. Pilawela Menike was his second wife. He had two more children with her and withdrew into quiet country life at Sirimalwatte – a rural hillside village off Kandy. Then on a trip to India he met Kusum Narayan. They were married in 1973. This, the third and final marriage was to last the rest of his life. George and Kusum travelled extensively, including a visit to London at long last. They even visited Pilawela Menike at Sirimalwatte where they received a warm welcome.

George however did have another great love affair, one that would last longer than any other. India. Keyt’s first trip to India was in 1939. Finally, he was face to face with the glorious realm of Hindu mythology he had read so much about. He could see, hear and feel everything that had inspired him from afar. He would return time and time again for varying periods of time to nourish himself on her ethereal energies.In 1940 he completed his most famous work – the murals at the Gothami Viharaya in Boralla which tell the story of Lord Buddha’s life. It is a grand combination of all his learning and skill that cemented his place as one of the true greats of eastern art. Later, in the 1940s he produced his famous translation of the Sanskrit classic – Jayadeva’s ‘Gita Govinda’. The series of line drawings that accompany it are considered to be some of the finest in that discipline.

The chief mover and shaker of the local art scene in the 1940s was the magnificent Lionel Wendt who set about organising the cream of local artists into a school of art that would spur Ceylonese painters into the modern era. Considering his stature as an artist, it was only natural that Keyt would play an integral role in that great gathering that came to be known as the ‘43 Group. There, he was in the elite company of his brother-in-law Harold Peiris, Justin Deraniyagala, Ivan Peries, George Beling, L.T.P. Manjusri Thero, George Claessen, Aubrey Collette and Richard Gabriel among others.

Most artists paint to live, but George Keyt belonged to the rarer variety of artists who lived to paint. Indeed he continued working right up until his death in 1993. In that time he created a vast body of work which is now in public and private collections all around the world. In their timeless excellence they prove his own point – “Good art is always new”. The 25th anniversary of Kala Pola, Sri Lanka’s celebrated open air street fair presented by The George Keyt Foundation and the John Keells Group, takes place on Sunday 25 February 2018 along the sidewalks at Ananda Coomaraswamy Mawatha. Free of charge and open to the public, it opens at 8 a.m. and continues until 9 p.m.