Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Friday, 5 February 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

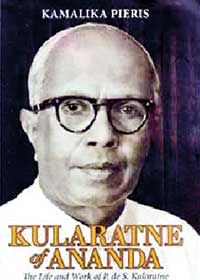

By Sudharshan Seneviratne

By Sudharshan Seneviratne

My memory about Principal Kularatne is entwined with the Senanayake family and my Alma Mater, Ananda College. My few and brief encounters with Kularatne were at the Kularatne Press where we were often busy with college publications. Seated at his table he probed each one of us about our subjects of study and our future plans. When he heard that I am fond of history and arts subjects, he gently told me that one needs math for any subject. He must have read my mind as I had an aversion for math. Mercifully, I did not have to deal with that misery at my AL’s but it came to haunt me as an archaeologist especially when we ventured in to Archaeological Sciences! Kularatne’s words of wisdom indeed.

Contextualising Kularatne

As a professional historian-archaeologist, I am personally gratified that this biography has chronicled an important segment of memory in our history. Memory in this country and in our history is short lived, selective, forgotten, subverted and often expunged. This biography narrates not only a portrait of Kularatne per se but importantly, a particular period in the history of Colonialism, responses to Colonial culture and the Colonial mind. Kularatne’s contribution was not a simplistic anti-thesis to Colonialism but posed a constructive alternative. He conveyed the prevalent ground realities in the early decades of Ananda in the following words:

“The history of Ceylon of the 19th century has not been written by a really competent, independent and impartial authority. When it is written…it will show that our ancestors of that period deserve no little credit for having remained true to their teacher and saved Buddhism from utter destruction of the powerful organisations which honestly believed such destruction was the greatest service they could render to Ceylon. “It is often said that Buddhists were backward in performing their duty by Buddhist children…If the Buddhists of Ceylon will examine carefully the services of the country today, they will realise what Ananda and Nalanda have done for them. …It is often said that Buddhists were backward in performing their duty by Buddhist children.

“An impartial non Buddhist student of history would record that it was a remarkable feat for the Buddhists to have achieved so much during the last few decades. …I remember Sir Graeme Thomson saying…that he was watching anxiously the progress of Ananda and Nalanda, because the success of such institutions showed the ability of Ceylonese to manage their own affairs, and augured well for the future of Ceylon.”

Ananda and Kularatne had a symbiotic relationship and were inseparably entwined with wider ramifications incorporating the common people, education, knowledge and wisdom, religion, politics, the next generation and futuristic visions. How do we evaluate individuals such as Kularatne and recognise the niche he carved out for himself in history? My reflections follow a trajectory. First, there is the Context; second, the Individual and third; Time and Space.

Understanding and evaluating Kularatne is futile without taking into account his context. Do let me first take up the individual and quote D.B. Dhanapala: “Kularatne was perhaps one of the greatest men produced in modern times. He was not only a teacher, and a brilliant educationist who set up a series of schools, he moulded men and was a pioneer in the nationalist movement. If greatness is to be measured by the amount of influence exerted by a man in his lifetime, then Kularatne ranks ahead of any other single individual of our time.”

As against this, here is a sober personal observation from Kamalika’s introduction to the biography: “He was a very placid person. In his simple dress of white cloth and shirt, he would sit quietly at our family gathering. He never made an entrance.”

This is the personality of a cultured and dignified individual. How should we evaluate the individual, measure him or her and situate the individual in history? There appears to be a dichotomy here. At the Trevelyan Lecture titled ‘What is History?’ delivered by Professor E.H. Carr at Cambridge in 1961, he advanced the notion that individuals do not make history. Carr’s underlying thesis was that it is the socio-cultural environment of a given time and place in history that produces individuals who come to be recognised as unique. Their thoughts and actions are a response to subjective and objective conditions that tend to steer the course of history designated with a particular identity – or what we call an ‘epoch’. My philosophy of life constantly faced a dialectical contradiction as to whether Great Men or Women made history, or conversely, social processes threw up such individuals in history. As much as I question individualism or ‘pudgala-vada’ on the role of the individual making history, there is a compelling bias on my part, towards the existence of ‘yuga-purusha’ or ‘yuga-kaantaa’ or ‘epoch-making’ man or woman and also ‘vishvapurusha’ or ‘vishvakaantaa’ ‘universal man or woman’. Sublime thoughts on ‘vishva’ and ‘yuga-purusha’ or ‘kaantaa’ prompted me to appreciate gifted individuals who possessed special qualities such as, humaneness, knowledge and wisdom and boundless tolerance towards other beings and nature. Such individuals I believe, and quite rightly so, possess beautiful minds. Thus I have no issue in situating Kularatne within this context where a symbiotic relationship nurtured each other. If one is to associate a particular epoch as the ‘Kularatne yuga’, then it must be designated with the characteristics of, both, the individual and time and space identified with the Colonial period and Ananda College. That carried a specific epoch-making identity in history – as the Kularatne Era. In short, if Kularatne was the actor, Ananda and Colonial Sri Lanka provided the stage.

The spatial factor: Mind and matter

Reading through the Kularatne biography, the author has identified and unfolded several aspects that run through his thinking, activism, engagements, his philosophy and vision. Chapterisation is built around Ananda, education, religion and culture and national politics with Kularatne’s personality running through as the connecting strand. It is a logical sequence from micro to macro context. Yet, he was not extroverted or paranoid in his thoughts and actions and looked at the bigger picture. Walking the same lines of Tagore, Kularatne viewed Ananda as an integral component of the South Asian intellectual mosaic and had a special affection for India and its culture as a source of inspiration, both, nurturing his anti-colonial sentiments and the higher culture disseminated at the Shanti Niketan – Vishwabharti ethos founded by Tagore. This was also the spirit and vision of the Founder Fathers of Ananda. I will not delve too much on the political life and thoughts of Kularatne.

For further information about the book please email [email protected].

To be continued

on tomorrow

The far-sighted contribution he made and his thoughts on the political dynamics of the transitory period in Sri Lanka and his visionary insights merit an entire book to his credit. It will be a must read corpus to most bankrupt and brain dead politicians who are entrusted with the governance of this country. Some years back I spoke at the 125th Anniversary of my Alma Mater on ‘Celebrating the Sacred Space of Wisdom and Humanism: Revering Ananda Maataa’. Ananda walked through history, through a painful path at that, to realise its designated historical role. Its life-line initially was sustained by the foundation laid by a host of Principals known to us as visionary educationists and managerial principals. Such dedicated individuals and their efforts peaked with Kularatne.

In a sense Kularatne’s period was the high point of convergence, a high point of this spirit, himself essentially being the catalyst.

He not only fine-tuned education and knowledge dissemination but embarked on a parallel planned infrastructure development and is rightly identified by the celebrated journalist, the late Mervyn de Silva, as the ‘Rebuilder of Ananda’. I do not hesitate to identify this period or the Kularatne era as the period of efflorescence in the history of Ananda and it rightfully may be identified as the Golden Age of Ananda.

The school elevated itself in numbers, modernisation of curriculum, improvements in academic performance and extra-curricular activities. Above all, Kularatne transformed the school in to a modern cosmopolitan academy and set the tone for the development of the total personality of the student. He did not hesitate to launch a massive fund raising program on a pan-island basis and with school carnivals for the first time.

Kularatne’s human resource management skills were displayed when he mobilised by attracting a brilliant staff that had individuals such as A.H. Sundar Raman, a botanist from Calcutta University, V.T.S. Sivagurunathan (Jaffna Hindu College and Ananda annually celebrate his memory with debates and cricket encounters), Ananda Samarakoon, C.V. Ranawake, T.B. Jayah, Gregory Weeramantry, C. Sundaralingam, G.P. Malalasekera and poet nationalist Ven. S Mahinda from Tibet among others. Arts, science and aesthetics thrived in this cultured bubble!

It was a period when the cosmopolitan character of the student body at Ananda became pronounced. In 1922 the college student census indicated that there were Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims, Protestant Christians and Roman Catholics among the pupils. Supreme Court judges P. Sri Skandaraja and V. Sivasubramaniam, as well as Dr. Kumaran Ratnam were students in the Kularatne era. There were even Tamil girls in the school’s lower classes.

There were Islamic boys and also a continuous flow of Burmese students and a few Indian and Chinese students as well. Kularatne provided religious training for most of them. Hindu and Islamic boys were taught Hinduism and Islam. He also established the Tamil Society and the Tamil Literary Association. Ananda also started teaching Tamil to the Sinhalese boys and Sinhala to the Tamil boys. Spoken Sinhala and Spoken Tamil were favourite subjects among students and even teachers.

Pluralism and respect for shared cultures

This is a high level of pluralism and respect for shared cultures. This good tradition continued during the Mettananda years, and would have gone on to the Wijayatilake years if the demand was there. By that time, there were sufficient acceptable Hindu schools available and the number of Tamil students at Ananda declined, which was also a result of the rising tide of internalised nationalism based on sectarianism. If continued, it may have resolved the suspicion and alienation between the two communities. We never learnt from the past and as a consequence ended up with a bloody carnage that bled this nation for 30 years.

In the early 20th century Ananda was not only a centre for renaissance culture and learning, but a place where anti-colonial, nationalist sentiments converged. In many ways Kularatne’s anti-Colonial spirit was translated in to action by many students and radical members of the academic staff. Most leaders of the early 20th century national movement and later those of the radical centre and Marxist movements in Sri Lanka were either educated or were associated with this school.

Philip and Robert Gunawardena, N.M. Perera, Bernard Soysa, S.A. Wickramasinghe and T.B. Subasinghe were among them. No school can boast of one of its students (Philip Gunawardena in this case) fighting against the fascist forces of Franco in Spain. The school took pride in itself not presenting itself as a lackey of colonialism while most other denominational and elite schools sponsored by the State were churning out subalterns in the service of the Empire. It is also during the Kularatne Era that several Indian national stars descended on Ananda.

Amongst them were Rabindranath Tagore, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sarojini Naidu and Rajaji maintaining alive connectivity between Ananda and India.

Past in the present and present in the past: Contradictions of post colonialism

Let us now focus on the legacy left behind by Kularatne and whether we have learnt from that past. By situating a modern and cosmopolitan educational rubric at Ananda and also by setting the stage for a national education policy, Kularatne expected to fine tune the total personality of the next generation while he never lost sight of the importance of higher education. Looking at post-Colonial developments in Sri Lanka, there is much we need to learn from his vision and much to be done to reorient our future planning for the sake of the next generation.

A major challenge posed by globalisation to contemporary nation states is the contradiction of retaining traditional value systems on the one hand and conforming to modernity demanded by global transformations on the other. Kularatne grasped this basic reality and its inherent duality and steered the course of the school, maintaining equilibrium between intellectual engagement and social activism.

We need to learn from the past envisioned by visionaries such as Kularatne, and recognise a dialectic that confronts us in relation to knowledge, its dissemination and its sustenance. They are two-fold:

The crisis in education that has led to the subversion of knowledge and the alienation of its primary stakeholders i.e. the next generation and public intellectuals.

An urgent paradigm shift, redefining the futuristic role of education and its primary stakeholders in a globalised world.

The failure to recognise dissemination of constructive and critical systems of knowledge-based education, especially in the post-colonial period, has unleashed anarchic and parochial responses from the next generation. They are increasingly moving towards social fascist and fundamentalist ideologies.

In contemporary South Asia there is an additional paradox caused by the appropriation of knowledge by two contending establishments. One is the persistent intervention by the State in education. Parallel to this, in the past two decades, the second factor emerged. That is, a growing effort to corporatise education and commoditise knowledge in market-oriented strategies by the private sector and, in some areas, in conjunction with the State. This contradiction was highlighted in Sri Lanka by two opposing slogans that read ‘Education cannot be given free’ and ‘Knowledge is not for sale’.

In the background are the dictates of the World Bank and IMF in formulating education policy and its implementation. This is Ground Zero of education. It has resulted in destabilising a situation that seriously threatens critical thinking, knowledge-based education, intellectual freedom and the independent existence of public intellectuals who are activists and engaged in the profession of teaching. It was Antonio Gramsci who highlighted the role of Public Intellectuals and their activist role leading to social emancipation.

Kularatne’s vision of an educated population from the non-elite and their right to have accessibility to education and information was integral to his visionary plan.

Some of the most challenging issues facing contemporary South Asian societies are humanising, democratising and decolonising knowledge and urgently providing remedial strategies to resolve this attrition. This is what Ananda provided before the nationalisation of education. This is also viewed as the foundation for the rise of an intellectually independent next generation. In order to place this ideal on track, public intellectuals and academic institutions must be released from the semi-feudal and backward capitalist psyche of the academic bureaucrats in the state sector on the one hand and the aggressive market-oriented predatory psyche of the corporate sector on the other.

A humane and egalitarian partnership between these sectors is viewed as the third dimension or alternative. An honest recognition and implementation of CSR or corporate social responsibility in Sri Lanka is a small but an invaluable step for a concerted pro-active attitude towards democratising education. Ananda must now intervene at the national level and provide its leadership towards national reconstruction and reconciliation.

For this change, a paradigm shift is an imperative. Kularatne envisaged this shift over several decades ago and the dual functioning of the national organisational structure in education.

“A few years after I assumed duties at Ananda College…I realised that the problem of education of our children could never be solved by the efforts of private individuals or organisations. The Buddhists as well as other parents had a right to that they do not wish to be indebted to A or to B or to C and to depend on the success of their efforts to provide the schools necessary to educate their children. A state system of schools is therefore the only solution to the problem in a democratic country in modern times. Parents have a right in a democratic country to ask the state to provide fully-equipped, well staffed schools for their children.”

However, Kularatne also saw the need to go beyond the narrow confines of the State in the management of select schools.

“Important schools like Ananda should be removed from the direct control of the Ministry of Education and should be handed over to an advisory Board of Governors representative of the old pupils, the parents, the public and the Ministry of Education. The Board should be given full powers to look after the funds f the school provided by the government and the parents. Instead of centralising power and dictating heads of schools like Ananda, decentralisation should be the policy.”

While noting the validity to democratise education and its management moving away from the present system of education that subverts knowledge, one of the priority areas is to de-link the state from the process of politicising education management and parochial text book writing. As text books became the New Testament of parochialism, Regi Siriwardena, an illustrious past pupil of Ananda, on his historical evaluation, highlighted this tragedy in a sharp comment. “In the history of communal violence in Sri Lanka….education has been one of the principal battlegrounds”.

Balanced road map

State-controlled education has outrun its functional use in the new pan-national and global context. As much as State financial support is essential and an imperative, it must step back from controlling the curriculum and teachers. Ananda could provide a balanced road map towards this end and relook at the former BTS administrative structure with modifications to suit contemporary concerns and needs. This was the vision Kularatne suggested.

However, Kularatne was also aware that, if mismanaged, the impending draconian rule by the management could be imposed on teachers, students and the school as a whole and consequently erode standards among teachers and students. Kularatne’s prophetic fears however, became real in a more primordial sense that has come to haunt our system of education.

Introduction of State control over education had a critical and destabilising impact on the nature of education, its dissemination and on national centres of learning – such as Ananda and most BTS schools. The good intentions and noble ideals of its promoters were crudely subverted. Sectarian biases and prejudices in general education and political interference at all levels of the educational edifice came to be institutionalised and an unhealthy norm has come to stay. The cumulative consequences in the long run were a culturally impoverished nation and the outbreak of several youth uprisings and a tragic separatist war of attrition.

Due to the national importance that Ananda acquired, the dynamics of social and political change in the post-Colonial period and especially from the 1960s onwards pushed Ananda to the centre stage more for negative reasons. Ananda became the guinea pig for several clumsy, unimaginative and counter-productive educational reforms injected as popularity measures by successive ignorant regimes and intellectually-challenged administrators. One Education Minister took upon himself a crusade against this school by diluting the primary school at Ananda. It took another decade to reinstall the primary school and control the damage. Professor J.E. Jayasuriya (Professor of Education, University of Peradeniya) recognised the “....narrow-minded, opinionated, compliant and mediocre bureaucracy in the Ministry of Education driven by petty careerism”. Unimaginative and uneducated politicians may be added to this list.

New pecking order

The new pecking order of schools that was put into effect by the State after the takeover precipitated an unprecedented rush for admission to National Schools (including Ananda). This undermined the carrying capacity of these schools and consequently they were unable to accommodate the ever expanding demand for student admissions and select schools (including Ananda) metamorphosed into townships exceeding a population of over 5,000.This destructive process was sustained on irregularities, corruption and a system of dependency and patronage. Quite naturally, quality of education had to be compromised for quantity. In stark contrast to the planned and gradual expansion of the number of students and infrastructure and use of time tested curricula that enabled visionary educationists and managerial Principals at Ananda to develop the ‘Universal man’ before the takeover, there was an almost anarchic growth in the student population, academic staff and infrastructure since the late 1960s.

One of the telling voids was the new generation of teachers who clearly did not have the academic excellence or dedication displayed by most pre 1960s teacher-mentors. The former flocked to Ananda, in the main, through political patronage and were ignorant of the history and traditions of the school, its intellectual ethos and ideals of inclusivity. To many such self-seeking teachers, the welfare of the student and knowledge dissemination had very low priority. This was a pan-Island abysmal tragedy and not peculiar to Ananda.

Such individuals were largely responsible for the creation of crippled and even suicidal minds within a knowledge-purging examination system that bred a self-promoting cancerous tuition system. All these had further drastically detrimental effects on the quality of education, time-tested cultural values, ethical behaviour and management of the College. Unimaginative syllabi, sub-standard and ‘puerile’ text books forced on teachers and students alike and the numbers game at O Level and A Level examination results made things even worse.

In my final year at Ananda (1968), I recollect a question posed by a classmate ‘whether the rapid vertical construction of new buildings, that are vulgar in taste any way, will ever elevate the quality of life and the inner spirit of the cultured minds of Anandians’. History has vindicated his sentiments. Instead of vertical monuments reaching for the sky, we should have constructed horizontal bridges so as to re-orient priorities towards enhanced knowledge-based education, to reach out to all communities, and play the role of a national catalyst – a role bequeathed to us by our illustrious predecessors such as Kularatne.

A school that had in the past produced ideologically radical and enlightened alumni who confronted social and cultural disadvantages imposed by Colonialism and plantation and merchant capitalism at home and challenged fascism in the international arena, was now incapacitated and unable to raise a ‘voice for the voiceless’ who were increasingly marginalised with the restructuring of a dependent economy in a globalised world. That ‘voice’ was raised, not by Ananda as it was under Colonialism, but by the poorer sections of the population and youth in rural schools who sacrificed their lives in search of social and economic emancipation and social justice by rising against a society that did not accommodate them with dignity.

Simultaneously, the growth of Tamil and Sinhala racism fuelled by religious fanaticism reached an ever increasing tempo due to the post 1980s ethnic war. Conversely, in the course of the war against separatist terrorism, many old Anandians were front line commanders and members of the defence forces who not only were actively engaged in battles but also sacrificed their valued lives safeguarding the lives of all citizens, property and a united Sri Lanka.

This is not to deny some landmark contributions made in almost every sphere by Anandians in the post-Colonial period. Individual students and teams excelled in sports, academics, literature, art, music etc in the past four decades bringing a great deal of credit to their Alma Mater. In spite of these achievements, we had lost something far more precious in our intrinsic identity. Ananda also needed to have engaged itself in a more positive role so as to provide an alternative to the wave of inverted sentiments of the mono-culture on both sides of the divide.

Historically, Ananda was entrusted with the task of disseminating wisdom and knowledge based on an uninhibited spirit of inquiry seeing things in their true perspective devoid of biases and prejudices and also in a spirit of accommodating and respecting divergent points of view. It also placed a high value on maintaining a perfect equilibrium by cultivating the heart and the mind, where one did not supersede the other. These were the ideals of knowledge enshrined in the spirit of Ananda’s ethos by its founding fathers.

Did we fail at the most critical time in the history of modern Sri Lanka to live by the real spirit of Ananda – an institution based on knowledge, wisdom, tolerance, inclusivity and principled action – that once embraced the nation irrespective of cultural, religious or ethnic divide and strived towards perfecting humanistic wisdom? Do take note of Kularatne’s words of wisdom and sentiments as ‘The greatest of all gifts is the gift of the Dhamma or knowledge. Ananda College is maintained for this purpose’. This line, in my personal view, should be the college motto.

Ananda must now intervene at the national level and provide leadership towards national reconstruction and reconciliation by setting the benchmarks for purposeful thinking and action. The very basis of our thinking towards the future must radically alter, to contest parochialism and embrace the historical reality of an inclusive Sri Lanka. The solution is to be found not in confrontation but seeking a practical way to build understanding and respect for diversity and plurality, a common platform to serve society as a whole in a country that has been vertically divided for nearly 50 years.

Unbiased and broad-based knowledge is the key. The late Ravindra Kumar, former Director of the Nehru Memorial Museum, noted that ‘knowledge is in theory communicable across cultural borders and persons of any cultural background are capable of using it’. It is in fact the universal language of people to people connectivity.

Kularatne and his immediate successors strived hard to nurture the physical and psychological well-being of the next generation and simultaneously safeguard the rights of the under-privileged as well as national pride. They did all the hard work and handed over the next generation to us as their custodians so that they will be treated and recognised with respect and dignity. Have we honoured that pledge? Let us sustain a living memory of all those who built Ananda and lived by their commitment towards the ideals of education, knowledge and wisdom as a gift to the next generation.

In his parting words on the 80th Anniversary of Ananda, the beloved institute he nurtured and gave glory, Kularatne conveyed these touching sentiments:

“Ananda is very dear to me…May she grow younger as she grows older!”

To end on a personal note, my lecture in 2014 at the Rabindranath Tagore birth anniversary celebrations was titled ‘pujaacha pujaneeyanam… to revere those who are worthy of reverence’. Kularatne too must be remembered and revered beyond the boundaries of Ananda and borders of Sri Lanka.

For further information about the book please email [email protected].