Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Friday, 28 August 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Shiran Illanperuma

The event

Cinnamon Colomboscope returned for its third and perhaps most ambitious iteration this year, as one of the city’s most promising annual arts and culture events.

Largely organised by the European Union National Institute for Culture (EUNIC) with funding from title sponsors Cinnamon Hotels and the likes of British Council, Goethe Institute et al, this year’s event tackled the complex themes of ‘city, identity and urbanity’.

The centrepiece of Colomboscope 2015 is undoubtedly the Shadow Scenes exhibition curated by Berlin-based Natasha Ginwala and Lanka-based Menika van der Poorten.

The exhibition showcases the works of 41 artists from across the globe and indeed “across Sri Lanka” – as the curators sought to emphasise – a fact that meant those from distant regions like Jaffna had to make the arduous trip home and back to cast their votes in the heat of pre-opening preparations.

The provocative project draws on art and artists that are not only intra-national, but also inter-generational and intermittent with foreign works that supplement rather than supplant the local talent.

Accompanying the main exhibition were a number of events that took place on 22 and 23 August at the Cinnamon Lakeside Hotel and Victoria Masonic Temple respectively. Building on the themes of ‘city, identity and urbanity’ a series of talks curated by Radhika Hettiarachi, featured the insightful participation of a number of civil society figures such as architect Madhura Prematileke, Centre for Poverty Analysis researcher Vijay Nagaraj, Groundviews founder Sanjana Hattotuwa, photographer Abdul-Halik Azeez and Yamu.com creator Indi Samarajiva, to name a few.

Early morning tours through the changing streets of Slave Island took place under the guidance of University of Kelaniya’s Asoka Mendis de Zosya while theatre veteran Tracy Holsinger curated a series of insightful and irreverent performances on 22 August evening.

The venue

Choosing the unlikeliest of locations, the Shadow Scenes exhibition is housed not in your typical bourgeois art gallery but in the heart of Colombo’s Slave Island, at the now abandoned Rio Hotel. Built in the 1960s by the enterprising Appapillai Navaratnam, the Rio set a gold standard as one of the first and finest hotel es tablishments in the centre of urbanising Colombo.

tablishments in the centre of urbanising Colombo.

This was not to last however, as in the euphemistically named Black July -the 1983 anti-Tamil pogroms that rocked the island and launched it into civil war- the building was looted and burned to the ground. The decaying structure with its cracked walls and peeling paint now stands as a monument to a bloody moment in this island’s history.

The Rio as it houses the Shadow Scenes exhibition is a different entity entirely. Ginwala states that the aim of utilising the grungy location was, “not just to regenerate the space but to rethink its history and the darker moments it represents”.

Indeed many of the artists seem to have viscerally responded to the space with installations that appear to emerge from the very architecture of the structure itself, casting ‘shadowy scenes’ as it were, in the haunting rooms and corridors of the building. 1990s Sri Lankan art veteran and exhibitor at Shadow Scenes, Jagath Weerasinghe says that the exhibition, “broadens the definition of traditional views on art in Sri Lanka by bringing in new materials, new mediums and most importantly; new ideas”.

Making one’s way through the narrow corridors, low ceilings and claustrophobic rooms of the Rio to experience the engrossing creations of the show’s artists is an appropriately daunting task that manages to evoke the density of Colombo, its inherent cultural pluralism and its lingering post-war traumas.

Exploring freely, themes such as militarisation and gentrification that may have attracted the ire of the state under previous regimes, the show is a much-needed critical reflection on the past in a present where we obsess over the future.

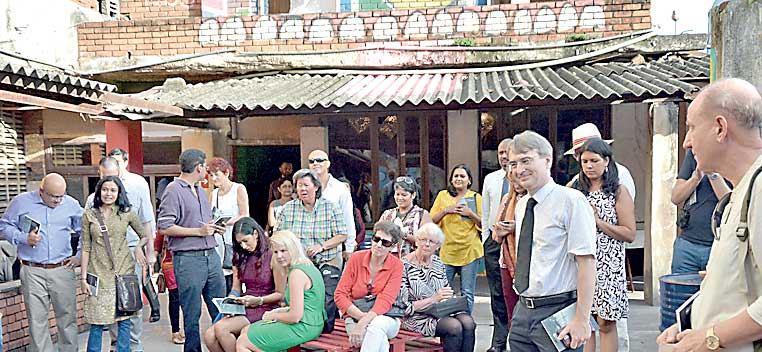

The contradictions

Attended by Colombo’s trendy youth, civil society paragons, intellectual elite and a smattering of expats and tourists, the vibe of Colomboscope exudes a metropolitan class and sophistication that is worryingly part and parcel of the city’s post-war aspirations. Thus while the discursive substance of the festival was refreshingly progressive, its effect of driving a predominantly middle and upper-middle class audience into the intimate spaces of Slave Island makes one wonder whether the festival is a commentary on gentrification or a symptom of it.

This irony was highlighted when Scroll.in editor Naresh Fernandes, discussed the “inevitable class barriers in globalised cities” while being hosted at a closed event at the posh Dilmah Tea Lounge. Indeed even the title sponsors, Cinnamon Hotels are implicated in Slave Island’s development through their ‘Cinnamon Life’ project, which is currently under way.

Perhaps most tellingly, the final event of the show, a party taking place in Slave Island’s dodgy Castle Hotel; attracted a bemused reaction from locals peering through windows and over shoulders, surprised at their watering hole’s temporary new clientele. Though admittedly, as the night encroached, the inter-class congregation achieved moments of utopian unison catalysed by the euphoria of booze and live music.

When asked about some of the seeming contradictions between the show’s progressive movements and its corporate and international funding, citizen journalist Abdul-Halik Azeez who has extensively recorded Slave Island’s development spoke pragmatically.

“The residents of Slave Island themselves do not necessarily object to urban development, the issue was the undemocratic way in which it was carried out at the time,” he says. Furthermore, Azeez advises against absolutes, arguing that artistic expression, which has traditionally been limited in Sri Lankan society, is now experiencing a renaissance thanks to an influx of private funding.

Perhaps then the genius of Ginwala, Van der Poorten and Hettiarachi’s curatorship, and the overall theme of ‘city, identity and urbanity’, is that it forces the audience to cast a critical eye on Colombo’s history and post-war development while simultaneously implicating them as active participators in the process.

Pix by Upul Abayasekara