Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Tuesday, 5 February 2019 00:58 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Reuters: Australia’s corporate regulators will be subjected to a new oversight body in a shake-up of the banking sector designed to combat the excessive greed and unethical practices that have engulfed some of the country’s biggest financial institutions.

The Royal Commission, Australia’s most powerful type of government inquiry, also advised in its landmark report on Monday that remuneration structures across the industry – used to reward everyone from bank sales staff to mortgage brokers – be overhauled to remove systemic conflicts of interest.

The report’s recommendations were largely supported by the conservative government immediately after its release. It marks the climax of a year-long interrogation of some of Australia’s biggest corporations and business leaders which wiped A$60 billion ($43.45 billion) from the country’s top finance stocks since hearings began one year ago.

The inquiry revealed misconduct had reached into the sector’s upper echelons, with AMP Ltd. engaging in board-level deception of a regulator over the deliberate charging of customers for financial advice it never gave, costing the fund manager its chairman, CEO and several directors.

The final report from Commissioner Kenneth Hayne, a former High Court justice who led the inquiry, found that the industry’s problems were exacerbated by an unwillingness by corporations to accept responsibility, leading to long delays in compensation payments.

“That is, there remains a reluctance in some entities to form and then to give practical effect to their understanding of what is ethical, of what is efficient, honest and fair, of what is the right thing to do,” the report said.

Watchdog bites

The Royal Commission made 76 recommendations in its final report that included a renewed focus on the corporate and prudential regulators which, it said, should be subjected to a new oversight authority.

Regulators were routinely accused throughout 68 days of Royal Commission hearings of working too closely with the banks. When misconduct was revealed, it either went unpunished or the consequences did not reflect the seriousness of what had been done, the inquiry found.

The Royal Commission used its final report on Monday to recommend that regulators use infringement notices for administrative failings, rather than issues that should be referred to a judge.

The institutional impropriety revealed during the past 12 months hurt some of society’s most vulnerable customers, highlighted by the case of a blind pensioner being persuaded to guarantee a loan without warning her of the risks.

In a separate incident, an insurer used aggressive sales techniques to sell an opaque product to a young man with Down Syndrome.

The report said 24 instances of bad corporate behaviour, including the wide-spread charging of fees for services not rendered, have been referred to the regulators for possible prosecution.

Australian Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said in a statement on Monday the government would act on all recommendations.

“The price paid by our community has been immense and goes beyond just the financial,” Frydenberg said.

“Businesses have been broken, and the emotional stress and personal pain have broken lives.”

The inquiry’s recommendations still need to be approved by Parliament.

Credit squeeze

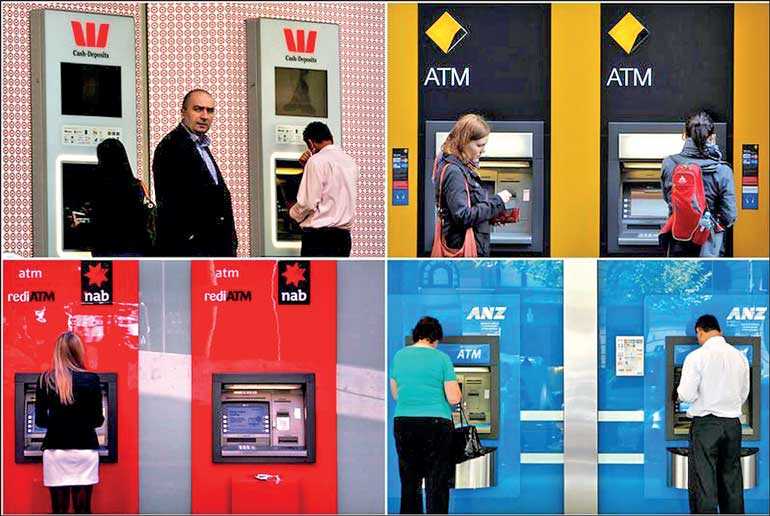

During 2018, investors responded to the punishing Royal Commission hearings by pulling their money from brand-tarnished insurers, banks and fund managers. Shareholders registered their distaste by voting against the executive remuneration plans of two of Australia’s biggest financial institutions, National Australia Bank and Australia and New Zealand Banking Group.

The two big banks, alongside counterparts Commonwealth Bank of Australia, National Australia Bank, and wealth managers AMP and IOOF, were among the worst hit by the inquiry, although wide-spread impropriety was also found in other sectors including insurance.

The conservative government formerly opposed a Royal Commission into the sector, arguing it would undermine investor confidence in Australia’s banks.

It then reversed its position amid widespread public and political pressure.

The report refrained from recommending any significant changes to rules governing housing credit, which was an issue that had previously concerned markets grappling with double-digit price falls in Australia’s two biggest cities, Sydney and Melbourne.

But the country’s mortgage broking sector is facing an overhaul of its remuneration structures, whereby the borrower – not the lender – will need to start paying the mortgage broker, disrupting a major channel banks use to increase their home loan books.