Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Wednesday, 3 January 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

LONDON (Reuters): After a year of double-digit returns, one of the key questions for emerging markets in 2018 is whether they will continue to be insulated from one another’s crises.

Contagion, an intrinsic feature of the sector for years, shrank to such an extent that an almost 10 percent drop in Brazil’s currency in a single day in May had little effect on its emerging market peers.

Was that proof investors now treat individual emerging markets on their own merits, rather than as members of a homogenous poor and crisis-prone bloc? Or was it just a function of central bank money-printing and near-zero interest rates?

Both played a part.

Not too long ago, a selloff like that of Brazil’s real currency on May 18 last year would have sent central banks in distant Asia and Africa scrabbling to defend their markets via interest rate rises or dollar sales.

Instead, its Latin American neighbour Chile cut interest rates with little weakening in its currency, while in the Middle East, Oman announced plans for a dollar bond.

Earlier that week, as the corruption scandal which exploded on May 18 brewed in Brazil, “junk”-rated West African state Senegal borrowed $1.1 billion on bond markets.

“Back in 2000, if Philippines sold off in the Asian morning, it meant Russia would sell off in the London morning,” said Steve Cook, co-head of emerging debt at PineBridge Investments.

Cook said his fund did not exit Brazilian markets on May 18, opting instead to shuffle the portfolio towards companies which would benefit from currency weakness.

“Brazil sold off because of political uncertainty but we knew it doesn’t impact Colombia or Peru from a macro perspective.”

But a 2008-style crisis emanating from the United States or China would still spark indiscriminate flight from emerging markets towards “safe” assets such as the Swiss franc, specialists say.

“The single-largest driver of EM performance is and will continue to be - growth. As we are seeing synchronised growth recovery, that’s what is underpinning relatively low contagion,” said Polina Kurdyavko, co-head of emerging markets at BlueBay Asset Management.

Kurdyavko bought Brazilian bonds after the selloff, judging that recovery from economic recession would continue and that “the fundamental story in Brazil is unchanged”.

Around half of the May 18 correction reversed over the following week as local and foreign funds snapped up bargains.

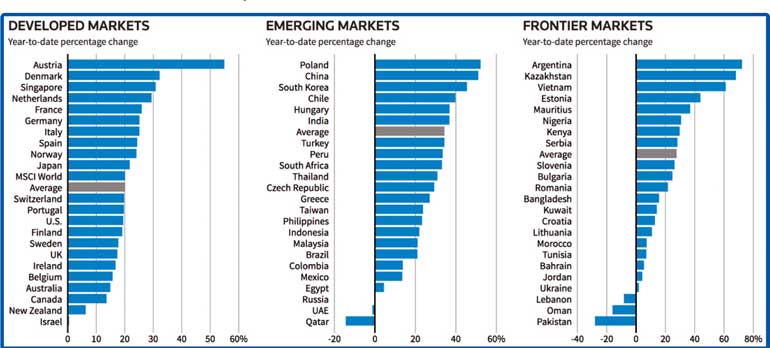

Emerging bonds earned double-digit returns this year, shrugging off Venezuela’s expected default, in a striking contrast to crises in Asia in 1997 or Turkey in 2001, shockwaves from which rippled through the developing world.

Change has been building for a while. There was little contagion from the July 2016 attempted coup in Turkey or Russia’s 2014 meltdown and even in 2013, the so-called Fragile Five developing countries were far worse hit than peers when the United States signalled plans to start unwinding its stimulus.

Russia’s decision on Dec 15 to cut interest rates by half a percent, just two days after the U.S. Federal Reserve raised rates, shows central bank policies are increasingly dictated by their own economic conditions, rather than the Fed.

Mexico and Turkey raised rates a day before Russia’s cut.

Expectations of more U.S. rate rises and the European Central Bank halving its bond buying will test individual emerging economies in 2018, emerging market veterans say.

But the sector as a whole is insulated by sweeping changes within the asset class and its investor base in the past decade.

Improvements made since turn-of-the-century crises are easy to pinpoint - inflation-targeting central banks, floating currencies, and borrowing that is now 80 percent denominated in emerging currencies rather than dollars.

Increasing numbers of investors have also come to view emerging markets as a structural rather than short-term trade.

That includes many Western pension funds which a decade back may have shunned emerging markets as too risky but are now raising exposure to benefit from the high yields on offer.

Thomson Reuters fund research firm Lipper tracks over 13,000 dedicated emerging bond and equity funds, up from about 2,000 back in 2003. And just in emerging debt, the most widely used GBI-EM index is used as a benchmark by funds managing $200 billion in assets, up ten-fold from 2007,

Because dedicated investors do not tend to bail out wholesale when crisis strikes, “a crisis in one country can be supportive for the other,” said Richard Benson, co-head of portfolio investments at Millennium Global.

Benson recalled when he started his career 15 years ago, most investment firms would have a tiny allocation to developing economies, just to diversify portfolios, whereas now 5-10 percent of total assets are likely in emerging markets

“So if there’s a crisis in Turkey, you underweight Turkey and buy Korea,” Benson added.

Other investors highlight the speed at which developing countries’ own savings pools are growing, allowing governments in the more sophisticated Asian, Eastern European or Latin American countries to meet most of their financing needs from local pension and insurance funds.

And these local investors not only stay put during selloffs, they also usually step up to buy when foreigners flee, limiting market falls.

Chris Perryman, a portfolio manager working with Steve Cook at PineBridge, noted for instance that up to 70% of new Chinese bonds are now sold within Asia, versus a fifth when he first started trading emerging debt 14 years ago.

“That’s due to the size of regional asset management capacity,” he said. “The dedicated flow has become more sticky and less likely to run for the hills.”