Saturday Apr 19, 2025

Saturday Apr 19, 2025

Monday, 27 January 2020 00:32 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By S. Thanigaseelan and Dr. K.A. Thulitha Wickrama

In an environment of financial unavailability, microfinance is a mechanism that can be used to uplift the people of post-war regions in Sri Lanka (Rathiranee & Semasinghe, 2012). Taking a page from the successful experiences of impoverished areas and families in the deep south (Galle, Matara, and Hambantota), some of the innovative Grameen banking and other micro credit methods they have successfully employed can also be applied here.

As the background for the need of lending institutions are identical in both regions (post-war areas in the north and east compared with poverty-stricken regions of the south), a comparison justifies a similar intervention.

Similarly, people are disadvantaged through the lack of facilities, resources, support, alienation, marginalisation, and social exclusion. As the basic needs of post-war north/east and rural south are the same – housing, material goods, living expenses, health and security – and with a view to enhancing their overall quality of life, micro-credit organisations are theoretically justifiable and practically already shown to have benefits for both regions.

In regions of extreme poverty and need, they stand as success stories of the movement started by Mohammad Yunas, the Grameen Bank guru to international development.

Various success stories abound, especially in regions with active rural development and poverty reduction programs through both Non-Governmental and Governmental Organisations. One such is the Grameen Bank-modelled credit organisation established in the Hambantota District (headed by GA Mithrerathne) to alleviate women’s poverty and empower them through financial self-reliance.

Established in the mid-1980s, this program is still ongoing today. The women’s self-help organisation in Hambantota was especially significant in the post-tsunami financial recovery of families. Similarly, the devastated post-war families are again experiencing even more desperate and needy circumstances.

While the tsunami region had the task of restarting already established businesses, the post-war region has the task of starting and developing businesses that never existed before at a level that can generate income.

Another program started under the stewardship of one of the co-authors (Wijaya Wickramaratne) over a decade ago is still ongoing today and serves over 2000 families as a Grameen Bank-based revolving credit society.

Showing the flexible and multifunctioning nature of credit organisations, this group not only initially gave each other loans for small businesses and housing development but later started organisation that owned and controlled businesses such as a cinnamon oil factory. Sanasa Bank and NDB Bank among many other private and public financial organisations have successfully engaged in this business over the years.

Micro credit facilities and organisations are not only financial but also social service organisations. In addition to the direct economic benefits for women, their quality of life improves through the impact their financial power has on their marital dynamics, resource acquisition, gaining skills and social status.

The evaluation of micro credit involvement among women shows that, due to these beneficial effects, women have clearly gained marital and community power, although poverty alleviation was still elusive. While escape from poverty may not be possible, it has shown significant financial benefits for associated families.

Programs especially showing success with women are crucial, as the population of greatest need in the post-war regions are women-headed households. With over 7,000 such families recorded in Kilinochchi District alone, the need for such micro credit organisations to bridge the gap between poverty and entrepreneur development is essential.

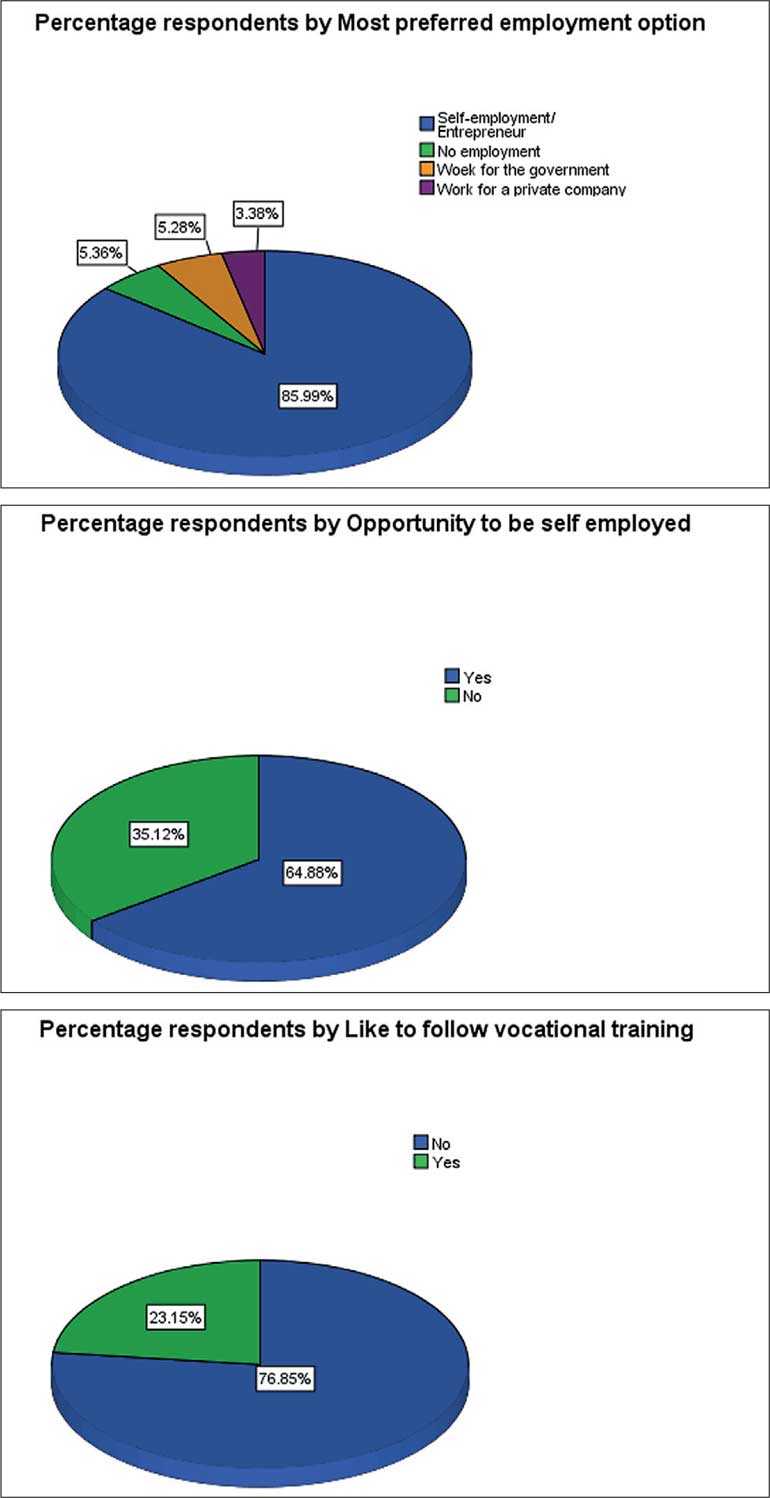

As they prefer self-employment and their biggest concern is lack of credit, intervening with micro credit organisations is a good fit. Moreover, there will be trickle down effects on the local economy, such as its impact on the high unemployment rates in post-war regions of Sri Lanka.

The focus group interviews of single women headed households clearly indicated their frustration at being isolated from banking facilities, business knowledge, supply chain, inefficient public sector and a clear lack of interest to engage with them from the private sector. Ironically, they themselves soundly stated the superior production capacity in their region in the daily and fisheries activities.

The discussion groups were clearly articulating the need to add value to their abundant raw produce and the need to find the most lucrative markets for their products. Again expressing their frustrations, the participants mentioned the lack of knowledge, facilities, and formal or informal social networks for them to accomplish these necessary next steps to grow their small businesses.

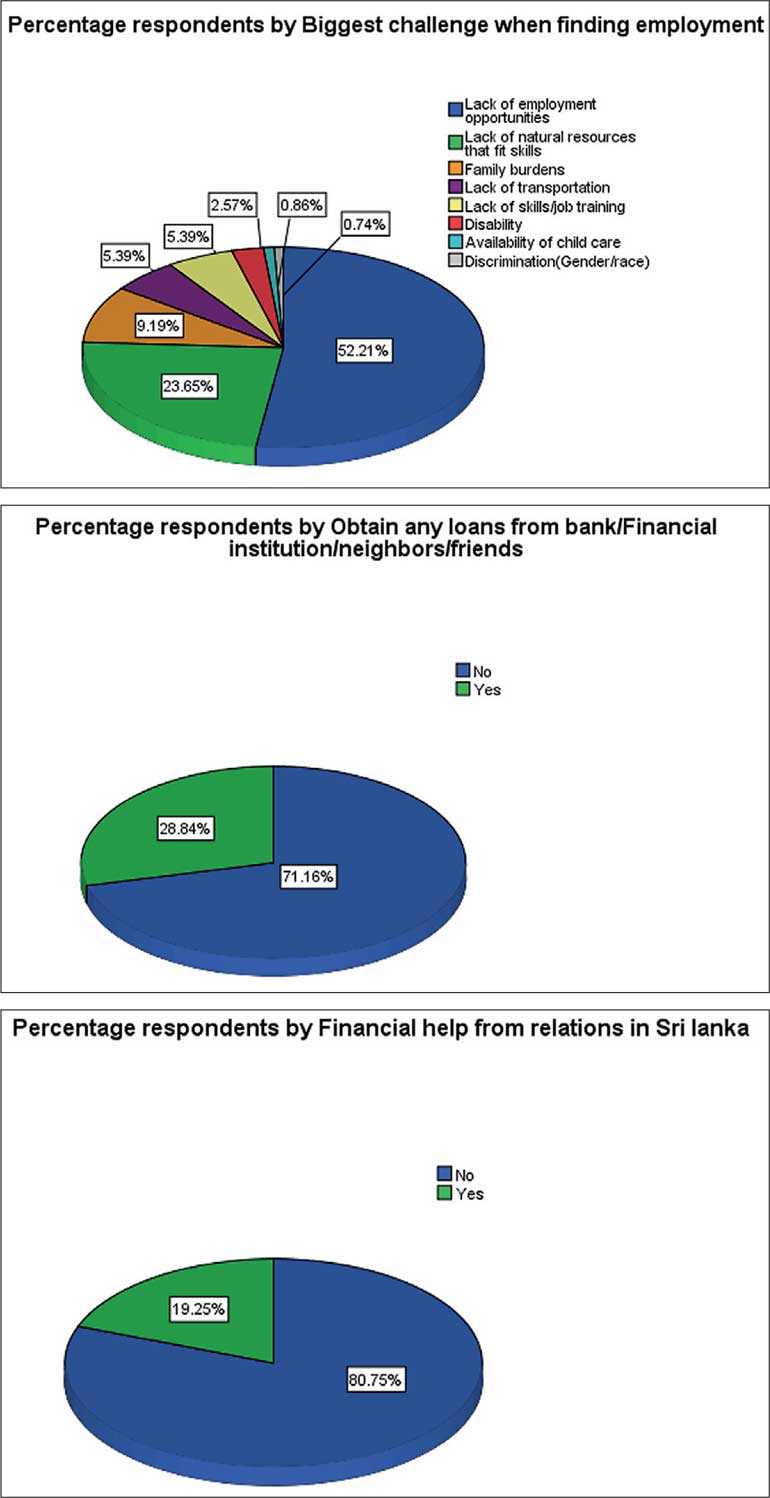

To quantitatively explore these financial needs expressed in the qualitative focus groups, the National Human Resource Development Council of Sri Lanka (NHRDC) conducted a census of the most needy families in the post war region—about 7,000 single-women-headed households.

Kilinochchi region and its people

Kilinochchi is not only a district affected by the recently concluded war, but also one affected by the 2004 tsunami. Previous studies have identified basic experiences of area residents related to water, sanitation, technology, facilities, schools and personal hygiene.

While these were critical aspects, no previous study has conducted a comprehensive assessment of factors that impact the influencing mechanisms behind income and employment needs of the most underprivileged segment of the population in Kilinochchi – single mother-headed families.

Such post-war areas of Sri Lanka are desperately poor due to disadvantaged social and economic circumstances. Socially disadvantaged families such as those in financial strain, those with less parenting support (e.g. single parent), families with lower level of educating, lower parenting skills, individuals with mental illnesses, those that lack social support or formal and an informal community network, and individuals specially in the developing work context suffer greater daily strains and stressful events.

The need to improve the lives of youth and adults that live under these disadvantaged conditions because of the risks to their health (behavioural, physical and mental), livelihood, career, trainings, and academic achievements, and the ability to live productive lives.

These families are economically disadvantaged with no business opportunities, credit facilities, banking facilities, lenders or access to markets, and are consequently left out of the supply chain and forgotten by investors and business opportunists.

Sample description

We administered in-person quantitative questionnaires to participants as follows: Poonakary DS division 953 and Pallai DS division 722.

In the Karachchi DS division we sampled 3,399 individuals (3,144 widows and 255 parentless households), while in the Kandawalai DS division we sampled 1,341 individuals (1,188 widows and 153 parentless households).

Individual interviews were also conducted with politicians, INGOs, NGOs, departments, CBOs, business persons, and religious leaders. As described previously, focus group interviews were conducted with widows and women in general. Of these, 86 interviewers were trained in Pallai and Poonakary in order to conduct this study.

Results of the survey questionnaire relevant to microfinance

Most engage in traditional agricultural and fishery industries; producing dairy or fish, as self-employment is the only practical option for most due to the lack of alternative employment and the availability of agricultural and fisheries resources.

They do not profit much from this work, as they are not knowledgeable in ways to add value to their products, have no facilities to do so, are unable to take their products to the market, and have no facilities to store, pack and fulfil other product-related needs. They sell their produce at far below market prices, often to a single vendor.

If they produce 100 litres of milk per day, they sell it for Rs. 49 a bottle to this single vendor, who in turn sells it for Rs. 60 a bottle in Batticaloa. As well as dairy work, many are also engaged in paddy cultivation, and repeatedly express their desire for training to conduct integrated farming. Other obstacles to financial wellbeing are transport and the lack of employment opportunities.

Moreover, it was impractical for these single parent families to leave their children unattended to go looking for work or conduct business activities away from home. There is distrust of the outside in sending their children to far away schools for higher studies.

Most of them are not interested in getting a vocational training mainly because the course schedules will interfere with their daily wage earning work; even if they were aware of its importance, divisions such as these still lack such institutions, and there is also lack of confidence in finding employment even after training at these institutions.

Many with previous vocational training need facilities and equipment to conduct their businesses. Many do not have the money to follow training courses that may develop their entrepreneur skills and are held back by family burdens. Related to the general area of finance is the fact that most of those engaged in labour do not have skills to manage the wages they earn (Rs. 1,000 per day).

Ways micro-financing can intervene

Due to the lack of employment opportunities, many in this post-war region have turned to self-employment as their preferred option. Microfinance can intervene as a stepping stone to facilitate this. Financing groups can be established by women’s and men’s rural development societies with a built-in monitoring system of borrowers.

Low interest loans for investments can be provided for promising members of a community. Assistance can be given to interested communities in order to organise themselves into financial self-help groups.

Compared to other regions that have used micro-financing with mixed success to due misusing of funds by powerful members of a community, the members of post war regions are equally powerless and need financial help from self-help credit organisations.

In forming micro credit organisations, post-war regions need special assistance due to the lack any prior experience in such activities. In doing so, they must be encouraged to co-ordinate their activities with a Divisional Secretariat (DS) and the local Grama Niladhari (GN) to avoid duplications and to locate the community members most in need of assistance.

Assessments of community members’ needs must be conducted with the assistance of the GN prior to awarding credit. Thus, the DS can help identify the communities while the GN can help select the individuals within them. An organisation that can act as guarantors and require no collateral is a welcome relief for individuals overwhelmed by their inexperience and severe vulnerability in the post-war regions of Sri Lanka.

The benefits of micro-financing are numerous for these poor communities. Firstly, subsistence-level entrepreneurs will be able make networks with other public and private organisations to grow their businesses in innovative directions and more profitable levels.

Secondly, these beneficiaries will use their existing resources to reap multiple benefits from previously profitable activities. Third, employment will be created through the beneficiaries’ successful business activities. And lastly, these to immediate and long-term economic and social benefits will create a higher quality of life and standard of living for their families.

(S. Thanigaseelan is the Assistant Director of NHRDC and Dr. K.A. Thulitha Wickrama holds a PhD in Human Development and Family Studies.)

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.