Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday, 16 November 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By M. Yusuf

In a letter to bond investors in July, a Senior Manager warned that “uncertainty is likely to crescendo through 2019 and as a bond investor, we are bracing ourselves for a messy and complicated election cycle ahead”, but concluded that “an investor has more than adequately been paid to take risk”.

The constitutional crisis that has unfolded since 26 October has now turned that sober assessment on its head.

For potential investors, the main points of worry are:

1. Sri Lanka has experienced an unconstitutional transfer of power, which is unprecedented. This means that political risks require re-rating.

2. As there is still no clear leadership in the country, the transfer of power is still contested. This means that no one is yet able to work out what the exact implications are.

The longer the uncertainty drags the worse the sentiment will be.

Duggen (2004) states that “extra-constitutional changes, however, appear to create a particularly acute set of problems”, and suggests investors look to the following in assessing risk:

1. Level of violence/disruption associated with the event

2. Experience of the leaders taking power

3. Likelihood of further recurrence of power grabs

4. Ideology or policies of the group taking power

So far, this has been bloodless but has wrecked confidence in the country’s institutions in the commitment to fiscal prudence, which was underpinned by the IMF program.

Following the takeover, the Finance Ministry announced a series of tax and price cuts on food, telecommunications and fuel. If implemented, these may breach the targets agreed with the IMF. Sri Lanka has already missed two IMF targets set for June. A statement by the fund on 27 September noted:

“With revenues falling short of targets, the focus should remain on implementing the new Inland Revenue Act and other tax policy measures, supported by modernised business processes to strengthen tax compliance.”

The IMF is yet to assess the impact of current developments on the program, but the rating agency Moody’s said the unfolding political crisis is “credit negative”, “heightens policy uncertainty”, and “could weigh on growth if social tensions rise, and threatens international investors’ confidence and the flow of foreign capital at a time when the Government faces large external debt maturities”.

“The change of Prime Minister and Cabinet raises uncertainty about the direction of policy. In particular, fiscal consolidation beyond the conclusion of the International Monetary Fund program in mid-2019.”

Investors may also factor in the danger of recurrence – the so-called coup-trap. Conflict analysts state that in smaller nations, the occurrence of one successful coup increases the risk of further coups (Collier and Hoeffler, 2007). Once the restraint the law holds is no longer inviolable, the danger is that others will follow; intra-party splits degenerating into power grabs.

A rating downgrade or the suspension of the IMF program would mean the country would need to pay much higher rates to compensate for the greater risk perception.

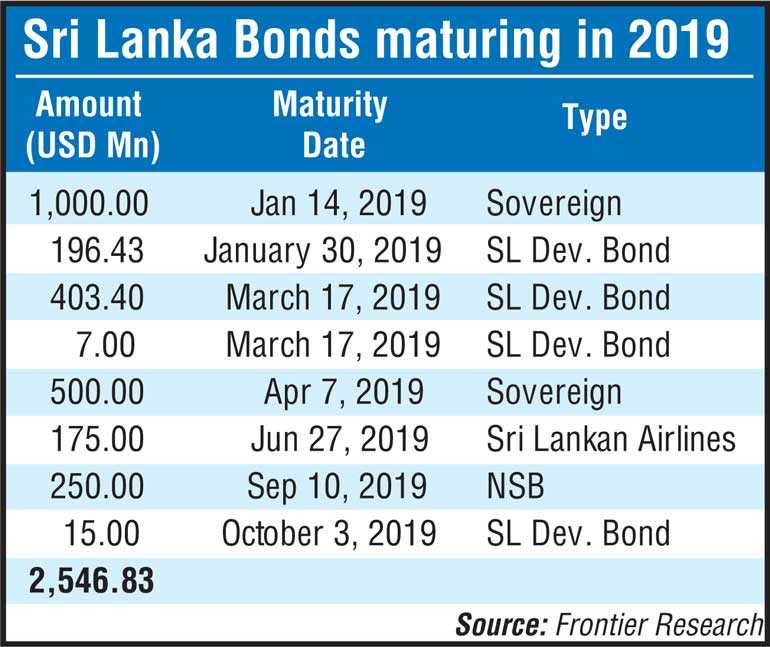

Approximately $ 1.2 billion of foreign debt falls due in January 2019 and a further $ 900 million by April. The list includes some quasi-Government debt for Sri Lankan Airlines and the National Savings Bank (NSB). These are ultimately financed by the Government – indeed it was the repayment of a $ 500 million loan from the Bank of Ceylon in April and another $ 750 million from the NSB in September that sparked the recent rapid depreciation of the currency.1

In early October, the Central Bank Governor indicated that the country would issue a sovereign bond before the end of the year, in addition to the billion dollar loan obtained from the China Development Bank. The Governor said that Sri Lanka needed to raise a sovereign bond as soon as possible before the US hikes interest rates. That plan is now stymied.

If the country was going to issue an international bond before the year end, it should have been launched in mid-November. Bankers estimate that it would take around a month to issue a bond and the financial market are all but closed in the second half of December. It will be difficult to turn to the markets until things have settled.

In the immediate aftermath fears of a possible debt default caused yields on some of the Sri Lankan debt to almost double (to around 9.99%) prompting the Central Bank to issue a statement to calm the markets. The CBSL says the Government has “already made pre-funding arrangements for meeting the maturing ISB obligations in 2019”.

Fortunately the Chinese loan was received a week before the crisis broke out and the CBSL statement may also have hinted at the possible solution. “While exploring an ideal window to further access international capital markets, GOSL and Central Bank of Sri Lanka have already initiated necessary actions to further diversify international market-based foreign funding sources to jurisdictions outside conventional Eurodollar ISB issuances”.

The CBSL does have reserves to repay the maturing debt, but this means it cannot afford to fritter this away in defending the currency. (Reserves stood at $ 7.9 billion at October end, down from $ 8.4 billion at end July, despite the receipt of $ 1 billion from China).

In the short-term a default seems unlikely, but in the longer term, debts maturing in the 2020 and 2021 (approximately $ 3.7 billion and $ 3.3 billion, according to the External Resources Department) need to be refinanced, but the question is at what cost? And who foots the bill?

In the short-term, turning to Chinese or other non-conventional sources may the most feasible option.

The public need to realise that Sri Lanka has a serious debt problem brought about by profligate public spending. Like a family that lives on a credit card, the country has been living beyond its means on borrowed money. Life may seem to be good, until the bill has to be paid.

Recent tax increases and adjustments to fuel prices have been very unpopular but necessary to repay debt. Debt is nothing more than taxation postponed and any new regime will have to face the reality of grappling with the same issues. Promises of easy remedies will quickly founder on the rocks of reality unless the fundamental problems are addressed.

Public spending has ballooned but the public see minimal benefits as the money is either misspent or stolen. From 2000 to 2016, total spending grew at a compounded annual rate of 12% (from Rs. 335,822 million to Rs. 2,333,883 million) with the deficit following suit (Rs. 119,396 million to Rs. 640,326 million). Foreign financing of the deficit grew from Rs. 495 million to Rs. 429,130 million in the same period.

The economy was already struggling in 2018, thanks in part to fiscal tightening and currency depreciation to which the Pohottuwa leadership was reacting. Yet the coup itself will probably impose yet more drag on the economy. A more difficult global trading environment and a fragile economic situation at home leave little room to manoeuvre.

Whichever way this crisis ends, the outcomes will be negative. For the sake of the country all parties need to recognise these dangers and work to restore some semblance of constitutionality to the system.

A legitimate dissolution of Parliament followed by a peaceful election campaign is probably the best way to restore confidence in institutions.

Footnote:

1 A full maturity list of quasi-Government debt is not available but the total Treasury guarantees on foreign debt to State institutions stood at $ 3 billion in December 2017. Since 2012, the debts of State entities were removed from the Treasury and recorded separately under SOE’s, meaning that these are no longer counted with official debt statistics and are now much harder to track.

(The writer is a graduate in economics)