Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Saturday, 25 September 2021 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike

|

|

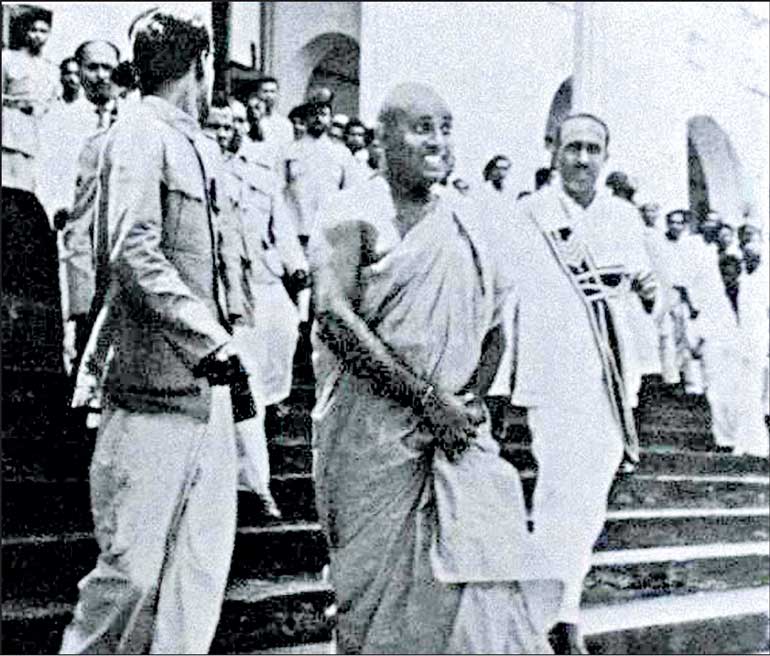

Somarama being led away from Court after conviction

|

By Chandani Kirinde

Defending a man charged with the murder of a Prime Minister is not the most popular or easiest thing to do. More so when the slain Prime Minister happens to be S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike who, in April 1956, less than three-and-a-half years before his killing, had led a coalition of parties headed by the newly-formed Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) to a historic and decisive electoral win.

As with most governments in power, the goodwill of the public at the beginning of his term as Prime Minister had begun to recede over the years but both his supporters and opponents were left in shock and grief by his untimely and tragic death.

It was on the morning of 25 September 1959, a Buddhist monk who had come to the Prime Minister’s residence at Rosemead Place, Colombo 7 on the pretext of meeting him over an official matter, pulled out a revolver and fired at Bandaranaike. He was grievously injured and died the following day in hospital.

Police investigations into the shooting began immediately and hours after the shooting, Rev. Talduwe Somarama was identified as the man who had shot the Prime Minister. He and several co-conspirators were identified by the Police over the next few weeks and the Magisterial Inquiry began on 14 December 1959, before Chief Magistrate Colombo N.A. de S. Wijesekera.

Seven persons were named as accused. In addition to Somarama, the others included Rev. Mapitigama Buddharakkitha, the then Chief Incumbent of the Kelaniya Raja Maha Viharaya, H.P. Jayawardena, Anura De Silva, Inspector of Police Newton Perera, a Minister in Bandaranaike’s Government Wimala Wijewardene and Carolis Amarasinghe – all close confidants of Buddharakkitha.

The purpose of the Magisterial Inquiry was to ascertain against which of the accused there was sufficient evidence to justify their committal for trail before the Supreme Court on charges of murder and conspiracy to murder. The Magisterial Inquiry concluded on 27 July 1960, and in the course of the inquiry Amarasinghe was granted a conditional pardon after he turned crown witness while an order was also made by the Magistrate discharging Wimala Wijewardene from the case.

The other five accused were committed to stand trial before the Supreme Court on charges of conspiracy and murder with Buddharakkitha named first accused and Somarama as the fourth accused.

Weeramantry takes on the case

It was before the start of the Supreme Court trial that the proctor for Somarama approached Attorney Lucian G. Weeramantry and asked him to undertake the monk’s defence. After some initial reluctance, Weeramantry had decided to accept the brief, bearing in mind that however unpopular his client may be given the nature of the charges he was facing, every individual was entitled to counsel and a free and fair trial.

Weeramantry, who went on to become an international jurist serving in several organisations including the International Commission of Jurists, published a book in 1969 based on his experience as the counsel for Somarama in the sensational trial. Titled the ‘Assassination of a Prime Minister,’ the book summarises the Supreme Court trial which lasted nearly three months, heard from 97 witnesses, and ended with the death penalty pronounced on three of the accused.

Dramatic events of 25 September

In the introduction to the book, the author sets the scene for the dramatic events that unfolded on the morning of 25 September 1959, which started off as another day of business as usual in the city of Colombo. While most were making their way to attend to their day’s work, a few were heading to the Prime Minister’s house at Rosmead Place with the hope of drawing his attention to some matter of importance to them.

Weeramantry writes that visitors to the Prime Minister’s private residence, where he had chosen to remain after being elected to office instead of moving into the official residence Temple Trees, had no difficulty in getting past the sentries at the two gates. “They had instructions to allow all visitors in except drunkards, mentally-unsound persons, and strikers. Those who arrived would usually sit in the long, open verandah till the Prime Minister appeared to have a word with them while some had to remain standing if all the seats were occupied.”

By 9:30 a.m. on the fateful day, around 40 persons were waiting to meet the Prime Minister. While they waited, the US Ambassador to Sri Lanka Bernard Guffler had arrived and was promptly ushered into the house where he had a brief conversation with the Prime Minister, at the conclusion of which the two men had come to the verandah and the Ambassador had departed. The Prime Minister was scheduled to leave for the USA on 28 September on an official tour.

After the departure of the US Ambassador, Bandaranaike had spotted among the visitors the eminent Queen’s Counsel Norman E. Weerasooria and invited him in and after a brief conversation the two men had appeared on the verandah and Weerasooria had left.

It was around 10 a.m. when the Prime Minister turned his attention to the other visitors. Weeramantry describes the visitors that day as a ‘motley collection including priests and peasants, pedagogues and politicians’. The Prime Minister had first spoken to an elderly man and then to a Buddhist monk. Then he had turned to another monk who was also seated when shots had rung out in rapid succession resulting in terror and confusion at the scene.

The Prime Minister and another man were injured in the shooting and were taken to the General Hospital, Colombo. By this time some of the people had overpowered the monk who was seen with a revolver in hand. He was later identified as Rev. Talduwe Somarama Thero, who had been a lecturer at the College of Indigenous Medicine in Colombo for some years and was a reputed eye doctor. By 8 a.m. the following day, the Prime Minister succumbed to his injuries. With a pall of gloom hanging over the country, Police investigations continued in earnest to apprehend those behind the heinous act.

The historic Bandaranaike assassination trial began on 22 February 1961, with Queen’s Counsel Justice T.S. Fernando C.B.E. presiding. A special jury of seven was selected after an exhaustive process with D.W.L. Lieversz, a Governmental electrical engineer, chosen as their foreman.

Crown witness, Carolis Amarasinghe

The first witness for the prosecution was Carolis Amarasinghe who had turned crown witness and was granted a pardon conditional upon him giving truthful evidence for the prosecution. An Ayurveda physician by profession, Amarasinghe was a founder member of the SLFP and was an ardent admirer of the late Prime Minister. He had been actively working on behalf of the Party which had brought him in contact with Buddharakkitha, the Head Priest of the Kelaniya Temple who was also the Head of the influential United Monks Front (Jathika Bhikku Peramuna).

The Front had thrown its weight behind Bandaranaike at the 1956 poll to ensure victory for the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna (MEP), the political alliance put together to face the United National Party (UNP) in the General Election. The UNP was routed in the poll winning only eight seats while the MEP won 51 seats.

The witness Amarasinghe lived in a house with a large garden on Baseline Road, Dematagoda and used a room there for his medical consultation. From his evidence it became clear that by mid-1959, some of the very forces that worked tirelessly to bring Bandaranaike to power had become his worst enemies.

Amarasinghe disclosed at the trial that Buddharakkitha had called at his house along with Somarama, Jayawardena and IP Newton Perera, first, about two-and-a-half months before the assassination, and a few other times. During these visits, Amarasinghe was privy to discussions they had on acquiring cartridges for a revolver and firing practices they were engaged in at Muthurajawela.

Amarasinghe claimed that on a day that Somarama called at his place alone, he had used the occasion to inquire about the reason for them practicing firing. The monk had replied, “To shoot the big fellow.” When he asked who he was referring to, Somarama had said: “Agamathithuma” (Prime Minister). Ruffled by the reply, Amarasinghe had forbidden him from coming to his house again if he and the others were plotting anything of that sort. About a week later, Buddharakkitha and Jayawardena had made a brief appearance and on seeing them he had walked up to their car whereupon Buddharakkitha had assured him that what Somarama said was not true. “We have abandoned all such ideas. Therefore, please don’t disclose what he said to anyone,” the monk had said and left immediately.

Between then and the date of the assassination of the Prime Minister, Amarasinghe said the accused men had not visited his place again expect Jayawardena who had come one day to get some medicine for his wife. On that occasion, Amarasinghe has queried about Somarama’s comments about shooting the Prime Minister to which Jayawardena had replied that it was all untrue.

On the afternoon of the day the Prime Minister was shot, Amarasinghe had got a call from Buddharakkitha telling him not to fear anything and to stay silent. By mid-October, Police had uncovered the connection between Buddharakkitha and Amarasinghe, questioned them and later remanded them along with Jayawardena.

Amarasinghe, whose testimony was key to prove the conspiracy theory, was cross-examined by the defence counsel, during which he contradicted several of his statements and did not answer when asked why he had not taken action to inform anyone about what Somarama had told him about plans to shoot the Prime Minister.

Buddharakkitha’s role

To elicit information on Buddharakkitha’s role in the assassination plot, the Court also heard from two residents of Kelaniya who knew Buddharakkitha well. In the course of their testimonies, it transpired that the monk had become displeased with the Head of Government mainly on grounds he was not given a say in important Government decisions and neither he nor his business associates were favoured by the PM.

The prosecution also called several witnesses who were residing close to the Amara Vihara in Obeysekerapua where Somarama had resided until his arrest. They confirmed seeing Buddharakkitha visiting the temple several times along with Jayawardena in the days before the assassination.

The Court also heard from a man servant who worked at Wimala Wijewardena’s house who said Buddharakkitha was a regular visitor there and the other accused too visited the house from time to time and they held lengthy discussions there.

Principal eyewitness to the shooting

The principal eyewitness to the shooting of the Prime Minister was a Buddhist monk named Rev. Ananda Thero who had come to Rosmead Place around 10 a.m. on the fateful day with some farmers to meet the Prime Minister. When he arrived, all the seats on the verandah were occupied but a young man who was seated had got up and given him the seat. Seated on his left was Somarama who was already known to him and the two had exchanged some words.

When the Prime Minister came out to speak to the visitors, he had first come up to Ananda Thero, saluted him and spoke to him and then turned towards Somarama and bowed to him. While raising his head, the Prime Minister began to ask Somarama the purpose of his visit, when a loud sound erupted. Ananda Thero who was looking in the opposite direction had immediately turned back and had seen Somarama holding a pistol with both his hands and pointing it at the Prime Minister. Ananda Thero had shouted “ammo” and involuntarily closed his eyes and then heard two more shots.

The Prime Minister

The Prime Minister who was wounded had rushed into the house and Somarama had run behind him with pistol in hand while Ananda Thero had run towards the gate to inform the sentry of what was happening. Amidst the melee, some persons at the scene had overpowered Somarama and were beating him up. A Police sentry who rushed there had opened fire, injuring Somarama.

The injured Prime Minister was still inside the house and Ananda Thero with several others had helped to carry him to the vehicle from where he was taken to the hospital.

Soon after he was brought to hospital, the Prime Minister was operated on by Colombo’s celebrated surgeon Dr. P.R. Anthonis. He was conscious and had spoken with the doctors. After the end of the operation which lasted over five hours, the Prime Minister had spoken again and described the assailant as a “foolish man in robes”.

During the trial, two other eyewitnesses and Constable Samarakoon who was the sentry on duty at the gate of the Prime Minister’s residence also gave evidence describing the scenes at Rosmead Place on the morning of the shooting.

Somarama’s stance

While all five accused were facing a charge of conspiracy to commit murder, Somarama faced an additional murder charge and had his own battle to fight. Before the start of the Supreme Court trial, Somarama had made a statement before Colombo Magistrate N.A. De S. Wijesekera on 14 November 1959, confessing to the murder of the Prime Minister.

He decided to retract that statement at the trial and made a statement from the dock in which he said he was forced to confess to the crime due to inducement from CID officers who had assured him he would go free within a few weeks if he made a confession. “I did not shoot the Prime Minister. If I said so it is false. My statement to the Magistrate was not made of my own free will. I am not guilty,” he said in his dock statement.

The verdict

The trial concluded on 5 May 1961, following which the presiding judge Justice T.S. Fernando addressed the jury and the jurors retired to consider their verdict. Five days later, the jury returned with their verdict. Jury foreman Lieversz announced they unanimously found Buddharakkitha, Jayawardena and Somarama guilty of the offence of conspiracy to murder and found Somarama guilty, in addition, of the offence of murder.

By a unanimous verdict they found Anura de Silva not guilty of any offence while by a divided verdict of 5 to 2, they found Newton Perera not guilty of any offence.

“Never in its history had the precincts of the Supreme Court witnessed such crowds as it did on 10 May 1961, the day of the verdict and two days thereafter when the court sat listening to the final statements of the accused,” Weeramantry writes.

In his address to the Court after the verdict, Justice Fernando made special reference to Lucian G. Weeramantry, the counsel for Somarama. “You (Somarama) have been defended by a counsel who has throughout these long and arduous proceedings exhibited towards your case a devotion which has been the admiration of everyone in this Court. But having regard to the strength of the evidence against you, there has been, in my view, no counsel yet born who could have saved you.”

The sentencing

The three convicted men were asked if they wished to make a final statement before the sentencing, which they each did to profess their innocence. Then came the grim task of sentencing the three men.

“Mr. Justice Fernando donned a black cap over his grey wig and rose grimly to his feet followed by the jury, the lawyers and the public. Then, in the breathless silence of an overcrowded Court, his Lordship solemnly passed the sentence of death on the first, second and fourth accused in turn.”

The Court of Criminal Appeal consisting of Chief Justice Hema Basnayake and four other judges subsequently altered the death sentences of Buddharakkitha and Jayawardena to sentences of life imprisonment, having accepted the argument of their counsel that the Act which reintroduced the death penalty for murder did not in specific terms reintroduce the penalty for conspiracy to murder.

The death penalty had been suspended by S.W.R.D Bandaranaike’s Government in May 1958. However, less than two weeks after his murder, the Government headed by W. Dahanayake reintroduced capital punishment with retrospective effect to make sure those found guilty of the assassination of the Prime Minister would be sent to the gallows. However, in the haste to pass the legislation, the Government of the day had left a loophole in the law by which the two main conspirators to the crime escaped the death penalty.

Somarama was not so lucky. He appealed to the Privy Council which reaffirmed the judgment of the Court of Criminal Appeal of Ceylon. On 6 July 1962, he was hanged at the Welikada gallows.

“The monk’s case was a very difficult one, but I felt that a lawyer should not refuse a brief because the case was hard, because the cause was unpopular or because the person killed was a Prime Minister. Every individual was entitled to the services of counsel and to a full and fair trial,” Weeramantry writes in his book, which is undoubtedly one of the most comprehensive books written on the Bandaranaike assassination case.

Buddharakkitha outside the Supreme Court