Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Tuesday, 19 December 2017 00:11 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka’s (B1 negative) high general Government debt, very low debt affordability, and fragile external payments position continue to present material credit challenges.

In particular, persistently high Government liquidity and external vulnerability risks will maintain pressure on the sovereign credit profile as large external payments come due in 2019-2022. Continued advancement of reforms that support fiscal consolidation and reduce external vulnerabilities under Sri Lanka’s current IMF program will be critical to mitigating macroeconomic risks and strengthening the credit profile moving forward.

Sri Lanka’s low tax efficiency and tax collection methods provide significant scope to broaden the tax base, increase its tax revenue/GDP ratio (13.5% in 2017) and eventually lower its elevated debt burden (just under 80% of GDP in 2017). Ongoing revenue reforms under the IMF program, particularly in tax policy and administration, will support a gradual decline in the debt burden over the medium term.

However, beside the implementation of the Inland Revenue Act – aimed at broadening the tax base through a simplification of the tax system – more sustained fiscal consolidation will be challenging. Moreover, contingent liability risks related to State-Owned Enterprise (SOE) will persist. As a result, material near-term improvements in Sri Lanka’s fiscal strength are unlikely.

While gradually narrower deficits will help reduce Sri Lanka’s sizeable refinancing needs, they are unlikely to narrow materially due to its very high level of debt and relatively short maturities. Moreover, particularly large external maturities are due in 2019-22.

With significant market access required to refinance maturing debt, including a sizeable portion denominated in foreign currency, Government liquidity and external vulnerability risks will remain elevated. Ongoing accumulation of reserves and implementation of an effective, predictable and transparent liability management strategy would support the sovereign credit profile by reducing uncertainty around the cost of future refinancing.

Sri Lanka’s growth potential and relatively large economy and high income levels compared with similarly rated sovereigns provide the economy with some shock absorption capacity and will help limit some of the risks from the country’s high debt burden. If successful, Government efforts to develop and promote exports, foreign direct investment and tourism would stimulate sustained higher growth over the medium to longer term and help mitigate balance of payments pressures, thereby reducing external vulnerability risk.

Q: Have recent fiscal reforms improved Sri Lanka’s sovereign credit profile?

A: Sri Lanka’s narrow revenue base and high debt burden are credit constraints. Whilst the Government is implementing a number of measures, we do not think that politically- and economically-achievable fiscal consolidation will be large enough to significantly alter the sovereign’s fiscal strength. As part of its three-year IMF Extended Fund Facility (EFF) program, the Government aims to achieve fiscal consolidation through revenue measures. It raised the VAT rate to 15% from 11% and is now in the process of reforming income tax. The program targets a reduction in the general Government fiscal deficit to 3.5% of GDP by 2020 from 7.6% in 2015. To achieve this, the IMF estimates that Sri Lanka will need a primary surplus of about 2.2% of GDP by 2020 from a primary balance of about 0.0% in 2017 and a primary deficit of 2.2% in 2015.

Thus far, the Government has made material progress in advancing fiscal consolidation, driven mainly by the VAT rate hike and tax administration reforms that enhance collection. Sri Lanka’s low tax efficiency and tax collection methods provide significant further scope to broaden the tax base and increase the tax revenue/GDP ratio, which was only 13.5% in 2017. Total Government revenues (combined tax and non-tax) are also very low, with a general Government revenue/GDP ratio of only about 14.8% in 2017, one of the lowest amongst the sovereigns that we rate.

The new Inland Revenue Act (IRA) is an important benchmark reform in Sri Lanka’s IMF EFF program, that will replace the existing income tax law with a more efficient and broad-based tax framework. It is scheduled for implementation in April 2018. The Government expects the new IRA to help drive an approximate 0.5% of GDP increase in Government revenues in 2019, following its first full year of implementation, and the IMF estimates that it could add up to 2.0% of GDP in additional Government revenues over the medium term.

If the Government’s revenue reforms, including the new IRA, are implemented successfully, we expect general Government revenues to increase to just over 15% by 2018. The IMF projects revenues to rise further to over 16% of GDP by 2021.

Overall, the Government’s revenue reforms will play an important role in bolstering fiscal consolidation given Sri Lanka’s weak fiscal position, the need for public spending on infrastructure and development programs, and political constraints in restraining expenditure.

Debt burden to decline gradually over the medium term, albeit remaining at high levels

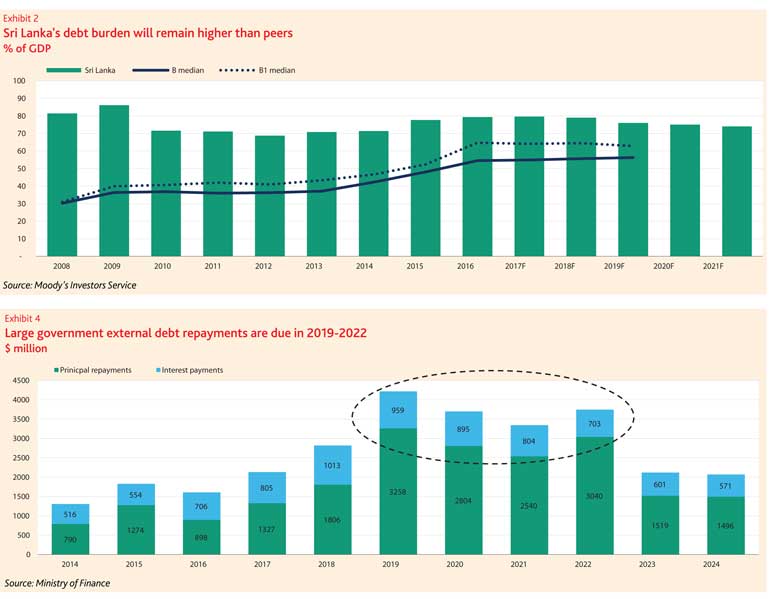

Persistent large budget deficits, combined with slower nominal GDP growth, have resulted in a rise in general Government debt to 79.6% of GDP in 2017 according to our estimates, up from its recent low of about 69% in 2012. As a result of recent fiscal consolidation efforts, we expect Sri Lanka’s general Government debt to stabilise near current levels through 2018, before declining gradually thereafter. While we expect the policymaking process to remain slow, due to the need for consensus

building, we believe that the commitment to fiscal consolidation is in place. Nonetheless, the debt burden will remain well above the median of about 55% for B-rated sovereigns and at a high level for an economy of the size and income levels of Sri Lanka’s.

Moreover, a number of financially strained SOEs with sizeable liabilities pose additional risks to the Government’s balance sheet, should financial support be needed. The IMF estimates that non financial SOE debt is worth nearly 12% of GDP.1 SOE reforms including the Statement of Corporate Intents and impending energy pricing reforms underpin the efforts to reduce fiscals risks to the Government. At this stage, the effective implications of the reforms for SOEs’ financial strength is unclear. Crystallisation of some contingent liabilities could add significant fiscal costs.

Q: What is your assessment of Government liquidity and external vulnerability risks?

A: The maturity and currency structure of Sri Lanka’s Government debt give rise to significant liquidity and external risks. Alongside with fiscal consolidation, these areas are a focus of the IMF programme. Liquidity and external vulnerability will be tested in 2019-22 when external debt maturities are particularly large.

Sri Lanka’s persistent annual fiscal deficits and large debt with short maturities result in a gross Government borrowing requirement (GBR) of about 19% of GDP in 2017, according to the IMF. While gradually narrower deficits will help reduce GBRs, Sri Lanka’s sizeable refinancing needs are unlikely to narrow materially. Overall, we expect GBRs to remain broadly stable at high levels well above the 10.3% of GDP median level for B1 and B2-rated sovereigns.

Directly related to large GBRs, Sri Lanka’s vulnerability to changes in external financing conditions is significant, as external and foreign currency debt accounts for about 43% of total Government debt (see Exhibit 3).

Moreover, the Government’s external financing needs will increase in 2019-22 when $15.0 billion of external debt matures (see Exhibit 4).

Sri Lanka is in the process of finalising a new Liability Management Act that will provide the Government with greater flexibility on managing future debt payments. The act is part of a revised liability management strategy that intends to provide the Government with increased flexibility around its annual borrowing ceiling, to better manage future repayments; address rollover risks and the bunching of repayments through extension of maturities; apply new debt management techniques (such as buy backs and switching); and update the bond issuance system.

The Government expects to introduce the legislative bill to parliament this month and hopes to enact it early in 2018. However, while the Government is taking steps toward addressing elevated external risks, it is far from certain that such measures will be sufficient to stave off rising balance of payments pressures.

At the same time, the central bank (CBSL) aims to improve the composition of reserves by winding down some swap lines with commercial banks and purchasing foreign exchange directly from the market. Already, CBSL’s reliance on swap lines has declined materially from around $3.3 billion in March 2016 to an estimated $1.8 billion as of end 2017. Nonetheless, at nearly one quarter of total foreign-currency reserves, commercial swaps still represent a sizeable portion of central bank reserves, exposing reserves to potential rollover risk. We expect the reliance on such swaps to continue to decline, though renewed pressure from capital outflows would jeopardise the credit positive trend.

Despite recent reserve accumulation, external vulnerability risk will remain elevated Supported by bond issuances (including a syndicated loan) and exchange rate flexibility, foreign exchange reserves (excluding gold and SDRs) have increased to $6.5 billion as of October 2017. Moving forward, we expect foreign-currency reserves to rise to about $7.5 billion in 2018, following the completion of the Hambantota port sale to a Chinese company. The sale will add about $1 billion in total to reserves by the middle of 2018. However, given the large volume of external liabilities due from 2019-2021, we expect reserves to remain around the $7.5 billion level thereafter.

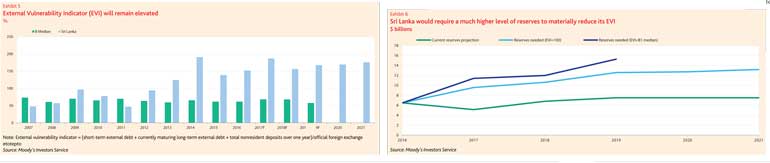

As a result, Sri Lanka’s external vulnerability indicator (EVI)2, which measures the ratio of external debt payments due over the next year to foreign-exchange reserves, will remain elevated, rising from around 152% in 2016 to about 187% in 2017. The EVI will decline next year with no international sovereign bond payments due, but it will pick up again in 2019 (see Exhibit 5).

As a further illustration of low reserves coverage, the following chart shows the level of reserves that would be required to reduce Sri Lanka’s EVI to 100% - where reserves fully cover short-term liabilities and maturing long-term liabilities - and to match the median level of reserves coverage amongst B1-rated sovereigns (see Exhibit 6).

Q: Will Sri Lanka’s GDP growth contain credit risks?

A: Sri Lanka’s growth potential, relatively large economy and high income levels compared with similarly rated sovereigns provide the economy with some shock absorption capacity and help limit some of the risks from the country’s high debt burden. If successful, Government efforts to develop and promote exports, foreign direct investment and tourism would stimulate sustained higher growth over the medium to longer term and help mitigate balance of payments pressures.

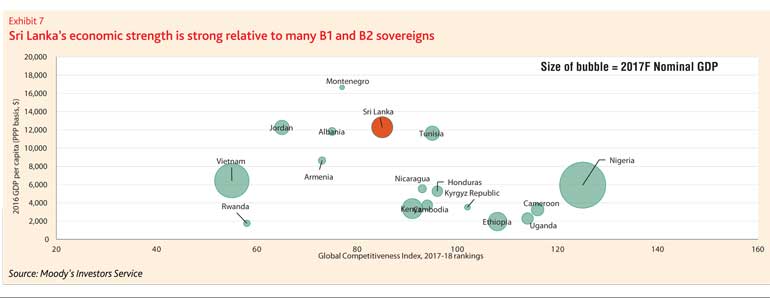

Sri Lanka’s economic strength metrics are strong relative to most B1 and B2 sovereigns Sri Lanka’s relatively large economy and income levels compared to B-rated sovereigns and robust real GDP growth drive our “Moderate (+)” assessment of Sri Lanka’s economic strength (see Exhibit 7). In 2007-16 the country’s 10-year average growth rate was 5.9%, and we expect real GDP growth to moderate to a still robust average rate of about 4.9% per year in 2017-21. In the shorter term, GDP growth has been affected by severe droughts and flooding in 2017.

Longer term, the Government’s pursuit of economic and structural reforms under its current IMF program will foster economic gains through improvements in productivity and competitiveness. We expect real GDP growth to recover to about 5.0% by 2019.

Growth potential supported by trade and foreign investment

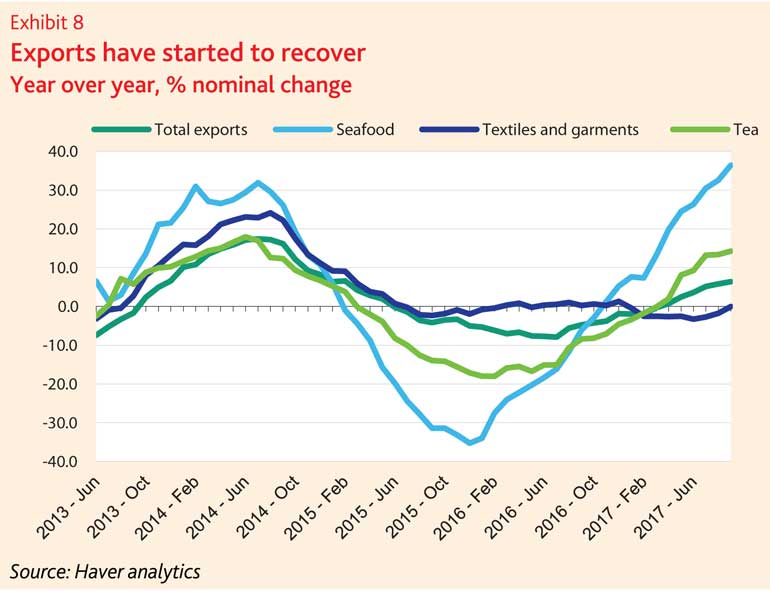

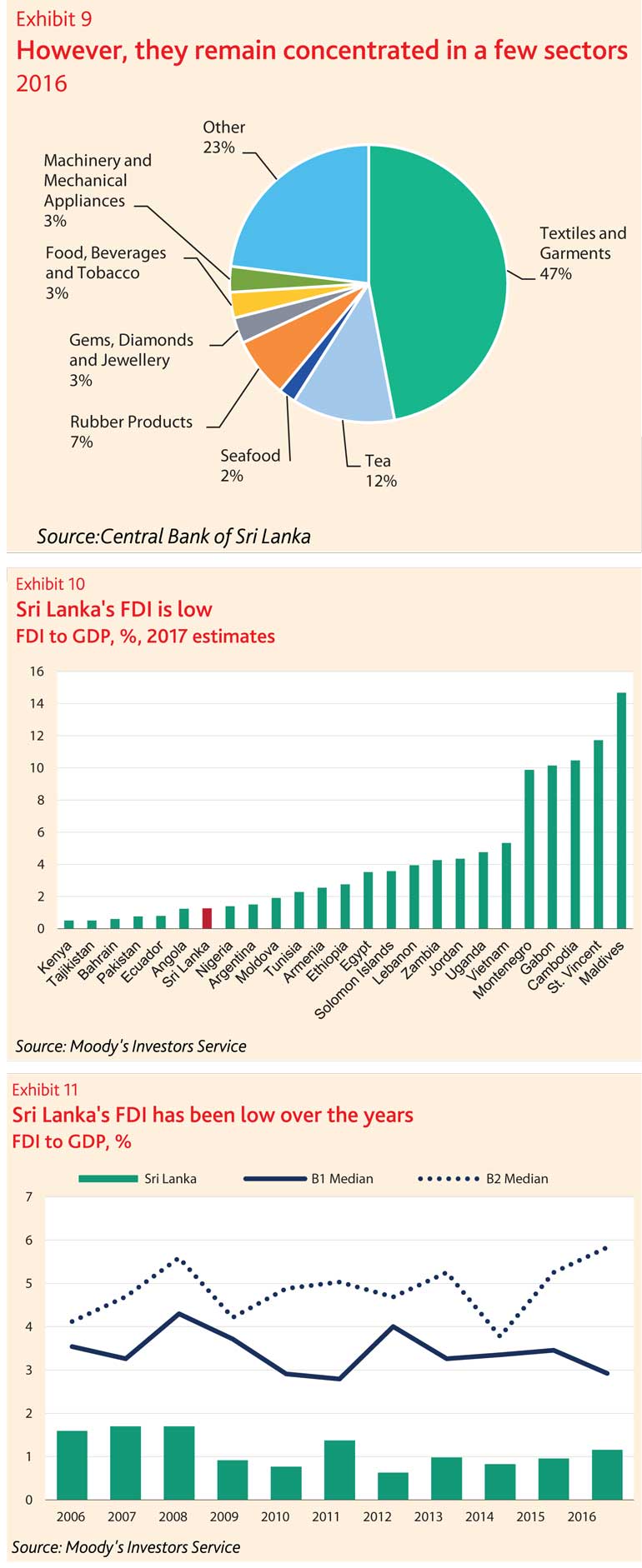

The concentration of exports in a few sectors increases Sri Lanka’s sensitivity to competition and sector-specific shocks; the EU fish import ban in 2015 is a prominent example of the latter. However, the medium-term outlook has improved following lifting of trade restrictions and GSP+ access in the EU, which is Sri Lanka’s biggest export market (see Exhibits 8 and 9). Sri Lanka’s strategic location along key shipping routes positions it well to benefit from increased trade, especially in South Asia. Sri Lanka has already expanded its port capacity. Moreover, the Government is actively pursuing Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with multiple trade partners, including China and Singapore. If such agreements are successfully signed and implemented, they will support gains in Sri Lanka’s export market share.

Meanwhile, the country’s geographic location and relatively strong socio-economic indicators are two factors favouring domestic and foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows in principle. However, net FDI, at 1.2% of GDP in 2016 remains low overall and compared to peers (see Exhibits 10 and 11). To promote FDI, and in line with many governments in the region and emerging markets in general, the Government is streamlining tax laws, improving the investment climate by implementing a single-window system for foreign investment applications, and instituting trade reforms which include strengthening the trade policy framework and improving the export competitiveness of local businesses.

The Government is also steering several large development projects, which should attract private investment and support economic growth over the medium term, including the Western Region Megapolis Plan, Colombo Financial City Project and Hambantota industrial zone. We expect the economic benefits of FDI to materialise gradually. For example, while the Colombo Financial City Project, which China is building and financing, will provide direct support to investment, the wider economic benefits of the project are thus far uncertain.

Footnotes

1 IMF Second Review under the Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility Report.

2 External vulnerability indicator = (short-term external debt + currently maturing long-term external debt + total nonresident deposits over one year)/ official foreign exchange reserves