Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Saturday, 2 November 2019 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

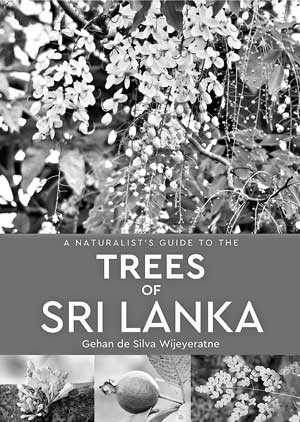

Written and photographed by Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne.

Published by John Beaufoy Publishing: UK.

176 pages.

Sri Lanka has a long tradition of books on trees, albeit biased towards the larger format and expensive end of the publishing spectrum. ‘A Naturalist’s Guide to the Trees of Sri Lanka’ is a portable, affordable, photographic field guide to 125 common trees published by British publisher John Beaufoy Publishing. This book complements their suite of Sri Lankan titles which cover a wide range of natural history subjects.

Sri Lanka has a long tradition of books on trees, albeit biased towards the larger format and expensive end of the publishing spectrum. ‘A Naturalist’s Guide to the Trees of Sri Lanka’ is a portable, affordable, photographic field guide to 125 common trees published by British publisher John Beaufoy Publishing. This book complements their suite of Sri Lankan titles which cover a wide range of natural history subjects.

The author and photographer, Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne, is well known for popularising and making accessible the identification of other categories of wildlife in addition to birds and mammals. An example being butterflies and dragonflies which he began to popularise with a series of simple and very cheap photographic identification guides he originated in 2001 starting with simple A4 sized leaflets to posters and booklets of increasing size culminating in a ‘A Naturalist’s Guide to the Butterflies and Dragonflies of Sri Lanka’ published also by John Beaufoy Publishing. ‘A Naturalist’s Guide to the Trees of Sri Lanka’ follows the same size and structure.

Sri Lanka has an estimated 800 species of trees. A comprehensive field guide to all of the trees will be a daunting exercise that could take several years of full-time effort to achieve. Many of the species of trees will be rare and confined to remnant and un-logged forests. The purpose of the new portable guide is to help people identify the common trees around them, both wild and introduced.

By combining botanical details with an accessible format, it also lays the foundation for people to gain the confidence to pursue an interest in plants at a deeper level. All tropical cities around the world have both native and exotic trees planted for shade and decoration. A walk down one of Colombo’s leafy avenues may reveal about 25 species of trees. But most people in Colombo (indeed in most cities) will be unable to name more than two or three trees.

Many trees which they think are native are in fact likely to be species introduced from elsewhere in Asia, Africa or even South America. Out in the countryside, local people have a better relationship with native trees and know their names. But they would not be able to know of an English name to use in a conversation or guided walk with a visitor from overseas or a domestic tourist from the city.

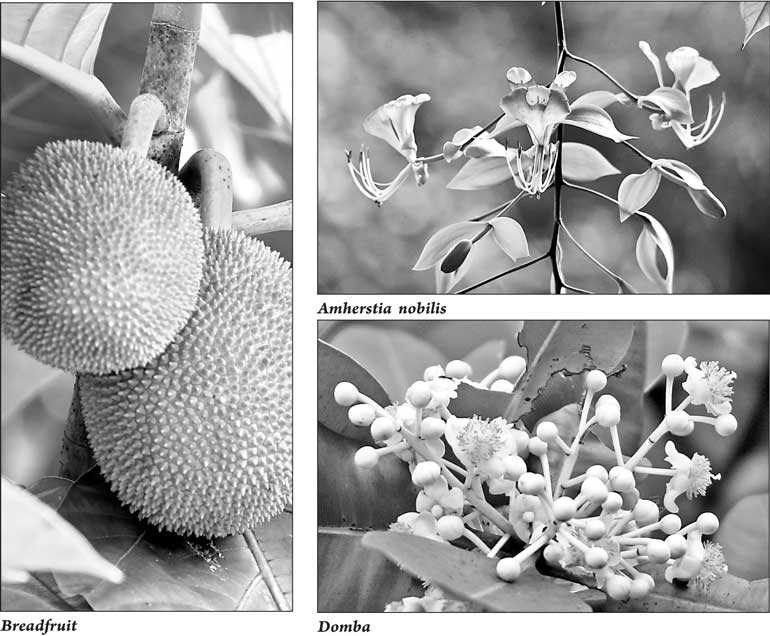

This portable guide is designed to help people from different geographies and backgrounds start putting a name to the trees and bushes around them. Key to this is the generous use of images. An attempt has been made to show as much as possible the leaves, bark, flowers, fruits and overall shape of the tree.

This is not easy and despite a phenomenal 540 plus images (all but two taken by the author) being used, the book is expected to improve with gaps in the images being filled over successive editions. Although aimed at the non-botanist, the book is structured to help newcomers get to grips with the basics of botany.

Trees are grouped by families rather than the other popular method of arranging them for example by leaf type. With birds, an eagle will look like an eagle and a stork will look like a stork. With trees, it is analogous to the same botanical family having members that look like an eagle, stork and a duck.

The author wants readers to be surprised that seemingly dissimilar trees are actually in the same family and understand their evolutionary relationships. For example, the sacred Bo Tree and the familiar garden tree, Jackfruit are in the same family. Furthermore, these two familiar ‘Sri Lankan trees’ are in fact introductions from overseas.

Each family of trees is preceded by a family introduction. The families are arranged by what is known as APG4. This is the fourth version of a taxonomic classification based on molecular genetics prepared by the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, a consortium of scientists working together in an international collaboration to classify plants based on their evolutionary relationship.

The text in the book avoids technical terms but includes an eight page glossary of botanical terms to help readers to progress to more advanced books known as ‘floras’. Key parts of plants including leaf shapes and the parts of a flower are illustrated and annotated so that readers can understand what to look for when identifying a plant.

The front sections include an overview of climatic zones, rainfall and temperature, habitats and top sites to help overseas visitors. Some of the main botanical gardens and arboretums are also mentioned.

Attention is also drawn to the grounds of some hotels such as those managed by Aitken Spence, John Keells, Jetwing and Serendib Leisure being akin to privately managed arboretums. Although not overtly mentioned, this in combination with the listing of tour operators in the end sections give a clue to the author’s well known agenda for monetising wildlife and thereby creating livelihoods in nature tourism.

The front section also contains an introduction to what is meant by a tree, the parts of a flower, pollination and dispersal and taxonomic classification. This helps to provide a context for the species descriptions whilst keeping the science of botany, bite-sized and digestible.

The bulk of the book, pages 24 to 166 in a 176 page book, is taken by the species descriptions which typically have at least a full page for each species but at times extends to two pages. The trees and shrubs represent 18 scientific orders and cover 46 botanical families. The author has taken a dual approach.

Firstly, the line of travel is highly visual to try and establish the identification of a tree by the use of multiple images. This will appeal to a wide audience, especially beginners. Secondly, the images are supplemented by concise text with a focus on identification. This will help those who are keener not only to distinguish similar species but to grow their confidence to progress to a deeper level by becoming attuned with what to look for in a plant and becoming familiar with features that botanists examine.

On a lighter level the etymology of names is provided. This breaks down seemingly impenetrable Latin names. For example, the Latin name Tamarindus in the Siyambala tree comes from an Arabic word and the generic name for Gal Karandha honours the great natural history explorer Alexander von Humboldt and Artocarpus in Greek means Breadfruit, the same as the English name.

The end sections contain a core bibliography, a list of useful organisations to join and acknowledgements where many State and private sector institutions and individuals who have supported the author’s efforts to brand Sri Lanka as a top wildlife destination are thanked for their support.

The author claims he finds trees a difficult subject and states that this book was written to help him as much as others. He hopes that this will be a stepping stone for people to get drawn into a deeper level of botanical study and perhaps even discover new species of trees in much the same way as his efforts to popularise butterflies and dragonflies enabled others to take up and pursue a scientific interest in those groups.