Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday, 31 August 2019 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Nature’s great masterpiece, an Elephant,The only harmless great thing;Yet Nature hath given him no knee to bend;Himself he up-props, on himself relies;Still sleeping sands

Nature’s great masterpiece, an Elephant,The only harmless great thing;Yet Nature hath given him no knee to bend;Himself he up-props, on himself relies;Still sleeping sands

– John Donne, ‘Progress of the soul’ 1633

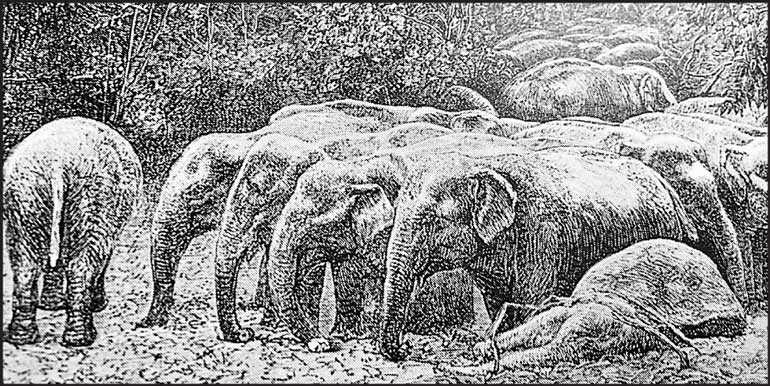

The poem has been quoted in ‘19th Century Engravings of Ceylon – Sri Lanka’ by R.K. de Silva in a chapter on ‘Elephants: Kraals and Hunting’.

How many elephants are there in Sri Lanka? The often-discussed subject is once again being talked about. The Wildlife Department, the way we normally identify the Department of Wildlife Conservation, is to undertake a survey mid-September. Around 4,500 persons are to be placed near waterholes where elephants gather and in forests for the count. They will work in teams.

When the last census was done in 2011 the number of elephants was given as 5,879 in all areas other than the north and the east. The survey could not be done in these areas due to the north east war.

Among the books written about elephants in Sri Lanka, I have found the one about tame elephants by elephant lover/researcher Jayantha Jayewardene quite interesting. In the Introduction he refers to an inscription at Navalar Kulam in Panama Pattu in the Eastern Province referring to a religious benefaction by a prince who was designated ‘Ath Arcaria’ or Master of the Elephant Establishment called the ‘Ath panthiya’. This means that the elephant has been associated with the inhabitants of Sri Lanka from the Pre-Christian era dating back to more than 5,000 years.

Ancient Sinhala literature dating back to 3rd Century BC refers to the ‘Mangalahatti’ – the king’s elephant. This elephant that the king rode on was always a tusker and the stable used for the elephant was called ‘hattisala’.

Robert Knox in ‘An historical relation on Ceylon’ (1681) refers to the elephant as “the beast so big and wise” and states that “few have Teeth, and they males only”. Obviously he was referring to the tuskers.

It had been the era when elephant kraals were held to capture wild elephants, which has been described as “the most remarkable and exciting scenes in the island of Ceylon to the Europeans” in a feature article in ‘The Illustrated London News’ (1847). Knox describes the way they are captured under the ancient king’s order:

“Unto these (the tuskers) they drive some She-Elephants, which they bring with them for the purpose; which when once the males have got sight of, they will never leave, but follow them wheresoever they go; and the females are so used to it, that they will do whatsoever either by word or a beck their Keepers bid them; and so they delude them along thro Towns and Countreys, thro the Streets of the City, even to the very gates of the King’s Palace; Where sometimes they seize upon them by snares, and sometimes by driving them into a kind of Pound, they catch them….,” Knox wrote.

The king made use of elephants for executioners. “They will run their Teeth through the body, and then tear it in pieces, and throw it limb from limb,” Knox writes.

He observes that as the elephant has the greatest in body, so in understanding also. “He will do anything that his keeper bids him, which is possible for a Beast not having hands to do. And as the Chingulayes (Sinhalese) report, they bear the greatest love to their young of all irrational Creatures; for the Shes are alike tender of anyone’s young ones as of their own: where there are many She elephants together, the young ones go and suck of any, as well as of their Mothers; and if a young one be in distress and should cry out, they will all in general run to the help and aid thereof; and if they be going over a River, as here be somewhat broad, and the streams run very swift, they will all with their Trunks assist and help to convey the young ones over. They take great delight to ly and tumble in the water, and will swim excellently well. Their teeth they never shed.”

Quote is from ‘An historical relation…’