Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Saturday, 8 December 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Seemingly without warning, and while he is still nine years old, Myshkin is abandoned by his mother. In Muntazir, which is as far as the railway tracks go, he is henceforth known as the boy whose mother ran off with an Englishman. Shortly afterwards, Myshkin is abandoned once again, this time by his father who, baffled by his wife’s desertion, discovers the need to find himself.

Seemingly without warning, and while he is still nine years old, Myshkin is abandoned by his mother. In Muntazir, which is as far as the railway tracks go, he is henceforth known as the boy whose mother ran off with an Englishman. Shortly afterwards, Myshkin is abandoned once again, this time by his father who, baffled by his wife’s desertion, discovers the need to find himself.

Traumatised by this experience of double loss, Myshkin withdraws into himself, emerging years later as an accomplished and retired horticulturalist, at peace with himself and the world – until a parcel arrives from Canada that he knows will in some way reveal the answers he has searched for all his life; answers about why his mother left so unexpectedly; answers he begins slowly piecing together.

In the words of Willa Cather, there are only two or three human stories, and they go on repeating themselves as fiercely as if they had never happened before. In this context, the events leading up to Myshkin’s story may not be remarkably unusual and could have many real-life parallels.

In pre-independence India, indulged by her father, Myshkin’s mother Gayatri has a passion for music and dance that she cannot let go. When her father passes away, her family ceases all indulgence and begins trying to marry her off. Getting wind of this situation and her availability, Nek Chand, an old student of Gayatri’s father, who had been an occasional visitor to their house, makes another visit, this time to offer Gayatri matrimony and a way out.

As you might have guessed, Nek Chand soon restricts Gayatri’s creative freedom by denigrating her artistic efforts and expects his wife to conform to a conservative vision of marital existence which begins to stifle her.

When the German Walter Spies makes an appearance in Muntazir and opens her eyes to an alternative lifestyle and opportunities outside her village, Gayatri decides to broaden her horizons and deserts the conjugal foyer. Forsaken without warning by his wife, Nek Chand who was both a respected teacher at a local college and a follower of the freedom fighter and spiritual guru Mukti Devi, responds to this crisis in his life by also leaving the child for an extended period of time.

The packet of letters from Canada does indeed confirm Myshkin’s worst fears and like Pandora’s Box reveals myriad different reasons for Gayatri’s unhappiness, providing unexpected twists and turns in her seemingly ordinary life. But in a way, it also provides closure for Myshkin’s life-defining moment of abandonment and his ensuing feeling of bafflement.

Anuradha Roy deftly paints a picture of a provincial stickler for form, a freedom fighter who was a tyrant at home, married to a creative many years his junior – both of them miserable in their own way, but due to societal conventions, locked into a perfectly mismatched marriage. Her skilful storytelling is such, that we will all readily identify similar stories we are familiar with.

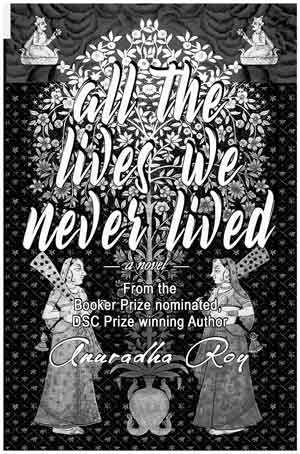

Hailed as one of India’s greatest contemporary authors, Anuradha Roy’s previous novels have appeared regularly on international prize lists. This year, All The Lives We Never Lived was long listed for the DSC prize, shortlisted for the JCB prize, and won the Tata Book of the Year award. She works as a designer at Permanent Black, an independent press which she runs with her husband Rukun Advani, in Ranikhet, India.

Hailed as one of India’s greatest contemporary authors, Anuradha Roy’s previous novels have appeared regularly on international prize lists. This year, All The Lives We Never Lived was long listed for the DSC prize, shortlisted for the JCB prize, and won the Tata Book of the Year award. She works as a designer at Permanent Black, an independent press which she runs with her husband Rukun Advani, in Ranikhet, India.

In Sri Lanka, Anuradha Roy is published by the Perera-Hussein Publishing House.

(Sam Perera is a partner of the Perera-Hussein Publishing House, which publishes culturally relevant stories by emerging and established Lankan and regional authors – for a primarily Lankan audience. Ph books are available everywhere books are sold and through www.pererahussein.com.)