Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Saturday, 27 January 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Madushka Balasuriya

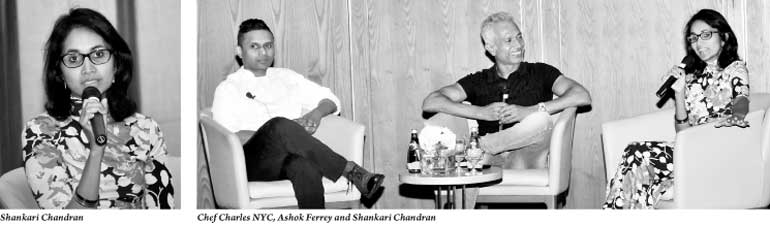

For an author who only a little over a year ago published her first novel, Shankari Chandran is certainly making waves. Having received stellar reviews for her debut effort ‘Song of the Sun God,’ which tells an intergenerational tale of family and heartache with ethnic tension at its root, her follow-up novel takes her creative stream in an altogether different direction.

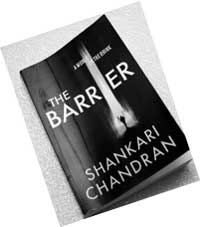

Having identified a gap in the literary field, and set out to write a dystopian novel for her children that was primarily focused on the eastern regions of the world, Chandran’s sophomore novel ‘The Barrier’ quickly transformed into one of a more adult nature with several overarching themes apposite for our times.

“‘The Barrier’ is a fast-paced literary thriller, set in a world destroyed by a virulent strain of Ebola and religious wars. It is 2040 and the surviving nations have been reorganised into the Western and Eastern Alliance. One side subjugates the other, using a vaccine, a virus and religion as its means of control,” reads a brief synopsis on her website.

The Australian author of Sri Lankan origin was on-hand at the latest gathering of the Silent Community of Readers, or SCOR, held at the Shangri-La Hotel Colombo earlier this week to speak about the book.

“I’m an empath and a lawyer. I watch the news and weep. I feel frequently overwhelmed by the weight of emotion in the world and yet I am a lawyer and I need to order the world with law and with language, which is why writing for me as a lawyer works really well,” Chandran says at one point in a session moderated by renowned Sri Lankan author Ashok Ferrey.

“Because when I’m working as a lawyer, I’m trying to fix things and create order using, and when I’m writing fiction I realise that I’m trying to fix things and create order with words, with language.”

In an engaging session which served as a prelude to Chandran’s appearance at the Fairway Galle Literary Festival, Ferrey, himself a literary heavyweight, manages to probe and get to the root of Chandran’s passion and purpose behind her literary work, while also unravelling her world view and the depth of her attachment to Sri Lanka. Following are excerpts:

In an engaging session which served as a prelude to Chandran’s appearance at the Fairway Galle Literary Festival, Ferrey, himself a literary heavyweight, manages to probe and get to the root of Chandran’s passion and purpose behind her literary work, while also unravelling her world view and the depth of her attachment to Sri Lanka. Following are excerpts:

Ashok Ferrey: I have read the intro that you have in your book and in the website and online. It doesn’t give us enough. You were a lawyer, you practiced in London for 10 years, you came back to Australia, you have four kids, you like chocolate. What sort of lawyer were you, were you a barrister?

Shankari Chandran: I was not a barrister but I’m frequently confused for one because I talk too much, I’m a solicitor and I worked at an international corporate law firm. And I ran their social justice program spread across 35 countries around the world.

AF: So social justice is something close to your heart?

SC: I have always been passionate about social justice. It’s always sounds contradictory to say that being part of a corporate law firm who’s reason for being is to make money, to also have a social justice program. It was a privilege to work in that field for 10 years, and I think in my writing I really draw on a lot of that experience.

AF: Were you actually born in Sri Lanka, do you have any connections from an early age?

SC: I was born in London. My parents left in the 70s to complete their training in London and from there they went to Australia, where – I was born in London, my brother was born in Canberra – we grew up and were raised in Australia in Canberra, which is the equivalent really of a small town.

We used to come back every summer in our childhood to Colombo and spend these wonderful summers with my grandparents in their home and all the cousins would return. And my parents’ generation would drop their kids and take off to India, and my grandparents were left fully in charge of their wilful grandchildren.

AF: Are they still alive?

SC: My grandfather passed away, and my grandmother is still very much alive; she turned 91 recently. The central characters in ‘Song of the Sun God’ are based on my grandparents.

AF: So you have connections although you weren’t born here and are not a Sri Lankan citizen, but you still spiritually feel it’s a part of your existence?

AF: So you have connections although you weren’t born here and are not a Sri Lankan citizen, but you still spiritually feel it’s a part of your existence?

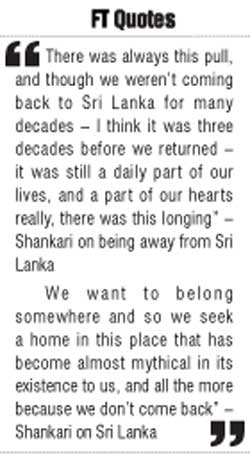

SC: Very much so, it’s a beautiful way to describe it. I do feel a very strong connection with Sri Lanka. Throughout our lives we stopped coming – actually after 1983, after the war broke out. And so we didn’t come back for decades and we lost that physical connection a little bit. Sri Lanka was always a presence in our lives because we were constantly aware of what was happening with the war. My family, particularly my father and his brothers really felt so much grief and loss, and anger, and guilt actually about having left and having survived and having gone on to create fortunate and wonderful lives for themselves in the rest of the world, in the diaspora. And so there was always this pull, and though we weren’t coming back to Sri Lanka for many decades – I think three decades before we returned - it was still a daily part of our lives, and a part of our hearts really, there was this longing.

AF: Why is it that there is this pull that this strange place exerts on almost all are expat Sri Lankan writers? And they’re not Sri Lankan either. Especially since it’s a very double-edged sword.

SC: It is. It’s like you’re of the place but not of the place. I think when you’re a diaspora – and I think it depends on which diaspora you are and which country you go to, where it is your new home is being built and how you are received within that community where you are at first either a refugee or an expat, and eventually a citizen – there is a sense of dislocation and a longing to belong, a seeking of your own kind and your own tribe. And I think fundamentally people are very tribal; we seek that which we know, we seek that which comforts us, that we can identify with, we seek what resonates with us. And for, I think, a lot of us in the diaspora we are the ‘other’.

Wherever we are in the international community – particularly in Australia because Australia has a very complex relationship with its ethnic minorities – we are very much ‘the other’. We are not of the place, and we want to belong somewhere and so we seek a home in this place that has become almost mythical in its existence to us, and all the more because we don’t come back. And there is of course a whole separate conversation about what happened when you do come back, and how you feel when you get here. So I think there is a longing to belong, a yearning, and a mythologising of your place of origin, your place of ancestry, the place your tribe came from, and a disconnect between the two.

AF: Moving on to your new book. What is so strange about this book is that it is a dystopic book, it is so futuristic, so bleak, and so harsh. What made you go in that direction? Because it has to be the first dystopian novel by a Sri Lankan writer.

SC: So my two older children were asking me if they could read the ‘Hunger Games’. Now I love dystopic fiction, it is my secret guilty, guilty pleasure. Dystopian movies, I love them. The highbrow, lowbrow, you name it I love it. And actually as a child I was planning for the end of the world; I was always stocking up on batteries and water and chick peas, and under my bed I always had a bag that was ready to go. And I’m an alarmist as well, I’m a lawyer, always planning for the worst.

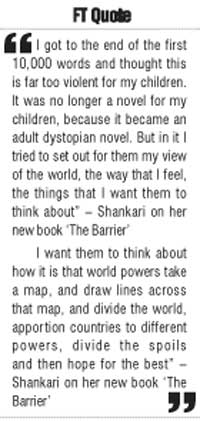

So I told my children they couldn’t read the ‘Hunger Games’ till I had read it first. And so I was binge reading a new generation of dystopian fiction, and at the same time watching the news. And then thinking that the news and dystopian fiction look alike! It was confusing and confronting and terrifying. And so I thought I’m going to write about this but I want to write for my children. So the first objective was to write a novel for my children that they could read and be proud of, that was set in the East – because the other thing that I was doing whilst I was putting ‘Song of the Sun God’ out in to the market, I was looking at the best seller list in the New York Times and The Guardian and literature was being dominated by Western stories, Western authors writing about Western issues and I wanted to write something set in the East about the East where the East and the West work together to save the world.

So I told my children they couldn’t read the ‘Hunger Games’ till I had read it first. And so I was binge reading a new generation of dystopian fiction, and at the same time watching the news. And then thinking that the news and dystopian fiction look alike! It was confusing and confronting and terrifying. And so I thought I’m going to write about this but I want to write for my children. So the first objective was to write a novel for my children that they could read and be proud of, that was set in the East – because the other thing that I was doing whilst I was putting ‘Song of the Sun God’ out in to the market, I was looking at the best seller list in the New York Times and The Guardian and literature was being dominated by Western stories, Western authors writing about Western issues and I wanted to write something set in the East about the East where the East and the West work together to save the world.

But I got to the end of the first 10,000 words and thought this is far too violent for my children. It was no longer a novel for my children, because it became an adult dystopian novel. But in it I tried to set out for them my view of the world, the way that I feel, the things that I want them to think about. Our present day world order, the political structure and the hierarchic structure that exists today, I want them to think about how that is actually based in history. To think about the historical context of the rise of power; who was colonised by whom and how throughout history? I want them to think about how it is that world powers take a map, and draw lines across that map, and divide the world, apportion countries to different powers, divide the spoils and then hope for the best.

I wanted them to think about terrorism, but not in the way that it’s presented to us, but to ask themselves, are we born terrorists? Or are we alienated and pushed to be radicalised? And to think about fundamentalism in all its forms. Not just, again, in the way its presented to us, not just Islamic fundamentalism but the fundamentalism that we invite into the walls of power, the fundamentalism that we invite into the White House, and to challenge that. So it was for my children as a cautionary tale that they will read in the future.

AF: One thing that strikes me about this book is that there is a huge amount of knowledge and research in it, that was very interesting for us lay people to read.

SC: Yes I’d done a tremendous amount of research in the book. I felt like I had done a degree by the end of it, and while I’m sure a lot of scientists will gladly discredit that, it has actually stood up quite well to scientific scrutiny. And I’m so pleased about that because I am very concerned with fact – which is the lawyer side of me – and I am also very concerned with fiction – which is the author side of me.

My father is a neurosurgeon, so there is a lot of neurology and neuroscience in this novel. He is also a religious academic. So throughout our lives whilst we were practicing Hindus, we were also raised with multiple faiths. So he practiced many faiths and studied many philosophies, many religions, and really indoctrinated us in those different philosophies and religions as children. And in late in life he’s become very interested in the relationship between faith and the brain. So when he finished reading this book he actually said to me, ‘my darling, you listened to me. You actually listened to everything I ever told you.’ And then he said, ‘please for the next one darling, maybe not so much swearing.’

Pix by Indraratne Balasuriya

SCOR Literary Salon

The Silent Community of Readers (SCOR) Literary Salon, since it was founded in 2009 by Sarrah Sammoon, has held more than 60 events of its kind, with the latest one arguably its most grand yet.

“It’s a space where we have intimate conversations in an intellectual world, where we also have fun doing that. But what matters most to the SCOR Literary Salon is what you bring to the conversation,” explained Sammoon of the exclusive club.

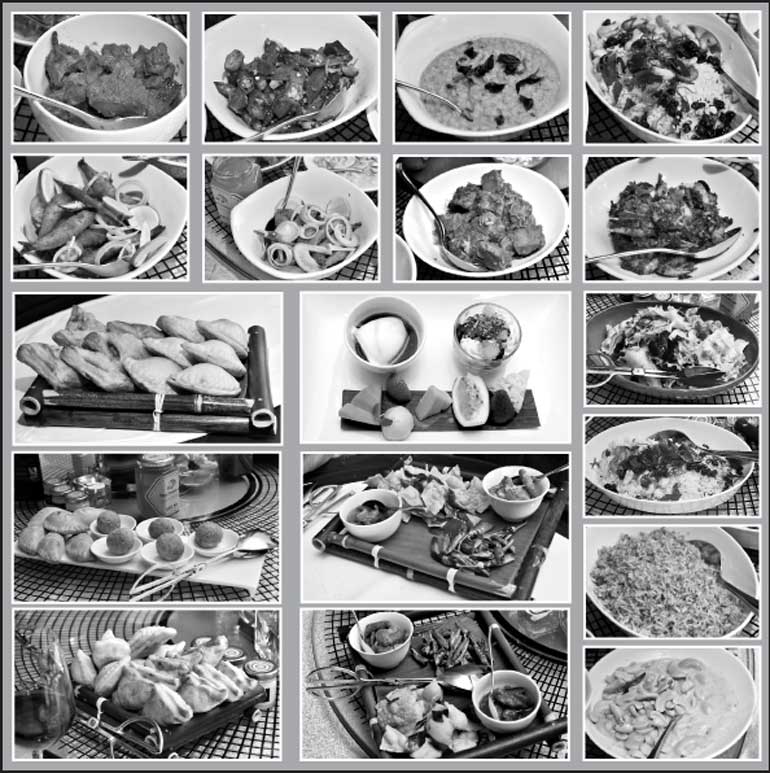

Joining in this time around in a fascinating interactive session with renowned Sri Lankan authors Ashok Ferrey and Shankari Chandran was another celebrity of Sri Lankan heritage, multi-award winning Chef Charles Disa.

Disa is the owner of the boutique catering company, ‘One World, One Kitchen’ based in New York, and he served up a treat with a lunch menu that included many native Sri Lankan dishes mentioned in Chandran’s new book ‘The Barrier’.