Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 14 October 2017 00:47 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Aysha Maryam Cassim

By Aysha Maryam Cassim

Sirimavo Bandaranaike is remembered for her unprecedented socialist, nationalist policies which were meant to develop the local industrial economy. Some believed that her statesmanship is what prompted Sri Lanka’s economic regression. But the artisans of Nattarampota today talk highly about former Prime Minister and the country’s political era from 1956-’65 and ’70-’71.

Even though Sirimavo’s regime failed to reap the expected benefits due to bureaucracy, political interference, lack of managerial expertise, capital, and technology, during her tenure, local art and craft industry flourished and machines at workshops were running at full pace.

It’s easy to see why the inhabitants of craft villages in Dumbara Valley still gloat over the good days in the ’70s. With the aim of empowering the local craft sector, in 1965, former Prime Minister launched a project in three phases under which around 35 families were settled in free lands around Nattarampota.

Shri Naredrasinghe Kalapuraya is an artisanal village where you’d find ambitious men and women, crafting the classics of Kandyan era in their cottage-based atelier.

How to get to Kalapuraya

Nattaranpota-Kalapuraya can be reached from Kandy in 30 minutes via A26 road. From Degaldoruwa Raja Maha Viharaya in Sirimalwatte, it’s only a 10-minute drive.

Ateliers in Kadupul Mawatha

When you walk past the houses in Nattarampota, Kalapuraya, you’d hear a hammering – the din of people making things. The brass workers are mainly clustered around Kadupul Mawatha, Kalapuraya.

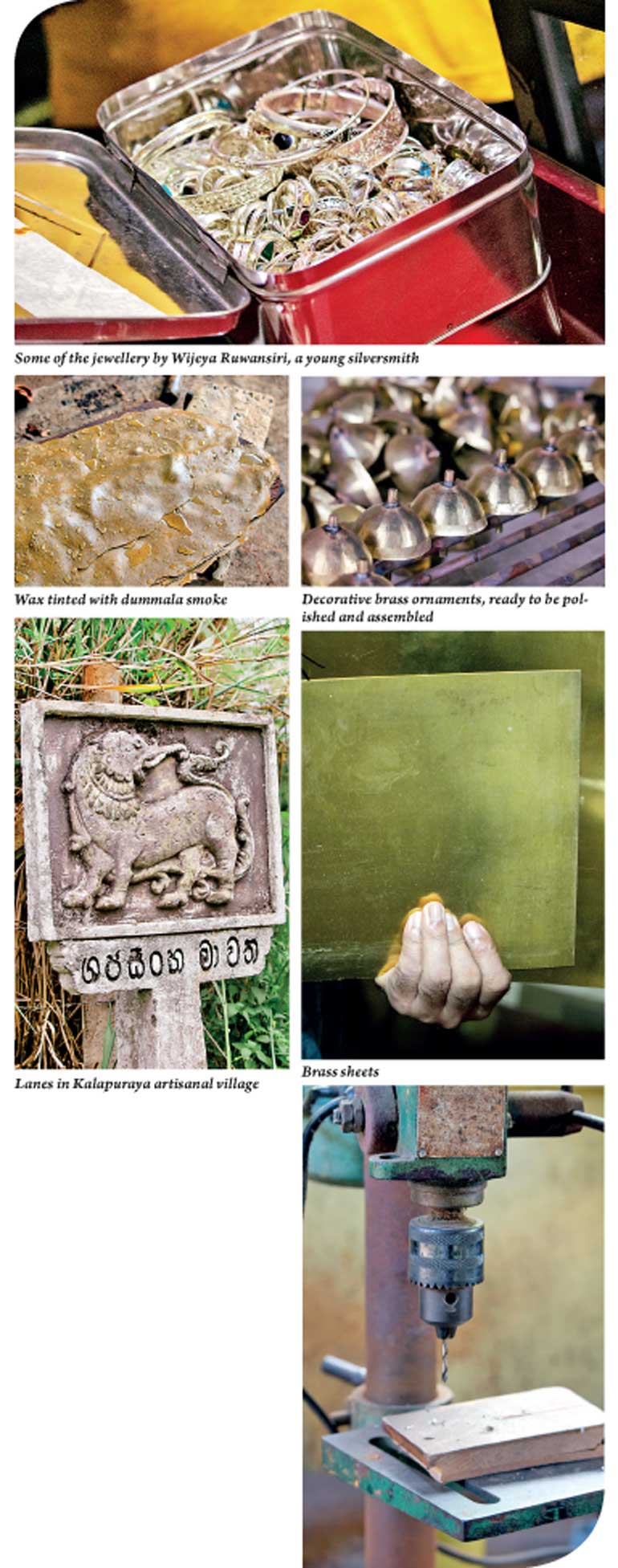

Curiosity made me stop by a house where a lady was busy cleaning the furnace of her outdoor studio. Dinujaya Brass Workshop has been manufacturing decorative brass ornaments for traditional oil lamps and Trishul for Hindu temples for 13 years. Their exquisite designs go to Laksala, in Colombo.

A conversation with Thilakarathne

The inhabitants of Kalapuraya are mostly second-generation artisans. In a fast-paced age where old craftsmanship and traditions are being forgotten, the brass workers, engravers, weavers and woodcarvers feel imperilled by competitors. The crafting techniques, which were totally manual, have now been mechanised over the last two  decades. Yet the demand for meticulously handcrafted ornaments still remains alive.

decades. Yet the demand for meticulously handcrafted ornaments still remains alive.

The demand for artefacts in the 18th century is rising and tourists are more concerned about the in-house production of the souvenirs they purchase. They want to know where it comes from and how it’s made.

P.G. Thilakarathne is an engraver who is taking the brass industry in Kalapuraya to the next level with innovative practices and entrepreneurship of his son. He was kind enough to spare his valuable time explaining the social dimension of the industry and how Kalapuraya became an integral part of Nattarampota’s brand identity.

Thilakarathne further emphasised the importance of working with materials in both modern and traditional methods and contemporary styles in order to keep up with the cutting edge industry. He spoke rather woefully about the plight of brass trade including the poor organisation of the workforce, outdated practices and political conflicts in trade unionism.

What is ‘Dambarang’?

Brass consists mainly 60% of copper and 20% of zinc. This is what people used to call as ‘Dambarang’ those days. The alloy may also contain metals such as lead, tin, iron, manganese, arsenic, etc., which may be added intentionally to improve the quality and strengthen the metal.

The brass that is being used today mostly come as sheets, imported from countries like India, Korea, and Japan. Unlike Dambarang which was solid, heavy and required constant maintenance to preserve the shine, the aluminium-based alloy which craftsmen use today appeals to the current market demands. Although lower in terms of quality, it’s less expensive, light in weight and has a yellow-golden tint that does not discolour or oxidise easily.

Making of brass caskets – Piththala Karanduwa

Artisans in brass workshops are exposed to metal fumes and see required to toil hours in the red-hot heat. The rigours of brassware design and their workmanship cannot be understated. There are several stages involved in the manufacture of brassware.

B.G. Mahindarathne is also a second-generation brassware worker who specialises in designing brass caskets aka Dalanda Karaduwa. With much enthusiasm, he briefly demonstrated the steps of forging an ornate brass casket that has been his superlative skill for 12 long years. He proudly held a finished casket and said: “My design is unique. Wherever this casket goes, I am capable of recognising my own work.”

Once you procure the metal, wax, and clay, the hard work begins. The laborious process consists of tinting the wax with ‘dummala’ smoke, smelting and the pouring of the molten metal into the casts made from clay. (‘Mati Bandinawa’) The final steps are followed by fettling and polishing, which is mechanically performed.

Meeting a young silversmith

I met a young silversmith called Wijeya Ruwansiri who provides bespoke service in jewellery designing. He maintains his workshop is a small space in his residence. Just like other craftsmen in Kalapuraya, he warmly welcomed me into his boutique and took me on a guided tour of his workspace.

It was fascinating to see him create jewellery with the application of manual dexterity and scientific knowledge. Some of his finest necklaces are made using precious gemstones and elaborate designs.

As he was showing me his designs ranging from ranging from earrings, pendants with traditional Kandyan motifs and elegant chains, Wijeya told me that the future is bleak for the handcrafted jewellery making industry. “The traditional crafts are at the risk of fading away and dying out. Pretty soon the artisans will disappear too,” he said.

The future of Kalapuraya

Kalapuraya in Kandy is a treasure trove for the artistically curious. Handcrafted brassware is a burgeoning industry in the world art market, which involves a lot of risk, blood, and sweat. The return is very low compared to the effort you exert for months around the fire. In addition to the fabrication of traditional art pieces, now the craftsmen have branched out into making fixtures and fittings for domestic and commercial clients such as wrought iron plaques, panels, medals, frames and decorative ornaments from brass, bronze, and steel.

Their work is labour-intensive and time-consuming. But one thing I observed is that the artisans in Kalapuraya, don’t engage in their profession solely for its monetary value but for the pure aesthetic pleasure which rewards them with a smile on their face.