Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday, 28 September 2019 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

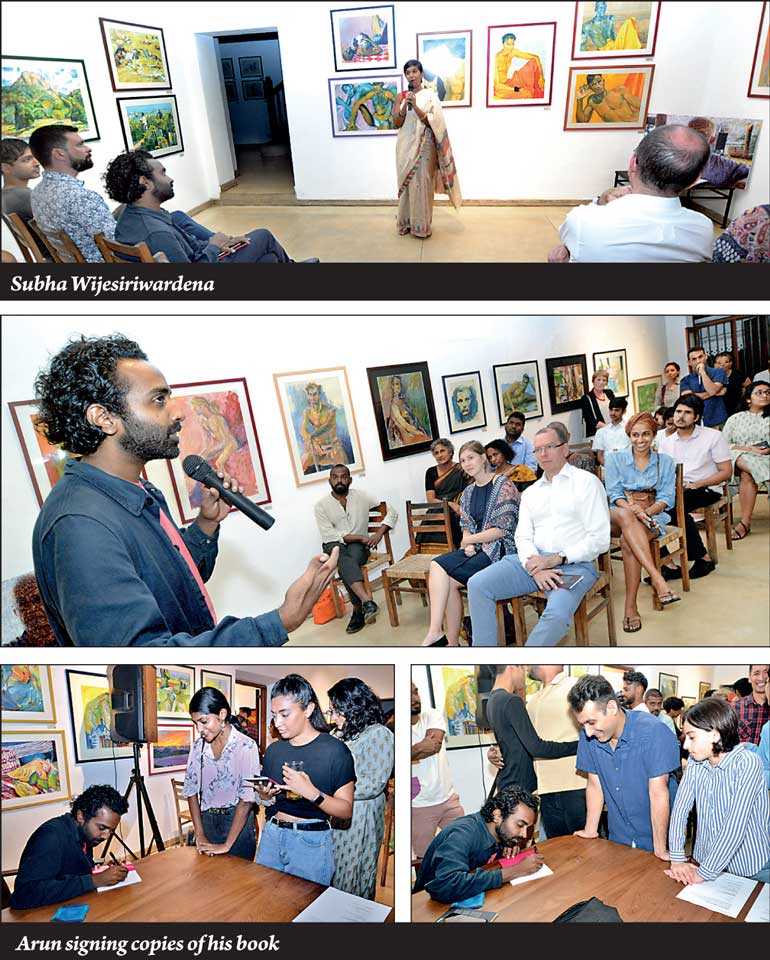

The launch of Arun Welandawe-Prematilleke’s ‘The One Who Loves You So,’ the winner of the Gratiaen Prize 2018, was held at Barefoot on 24 September. The evening also marked the official launch of the fundraising drive for the 2020 production of the show. Speaking at the launch were Ramya Chamalie Jirasinghe, Sandev Handy and Arun Welandawe-Prematilleke, with Subha Wijesiriwardena managing the event. Following is Sandev’s speech:

The launch of Arun Welandawe-Prematilleke’s ‘The One Who Loves You So,’ the winner of the Gratiaen Prize 2018, was held at Barefoot on 24 September. The evening also marked the official launch of the fundraising drive for the 2020 production of the show. Speaking at the launch were Ramya Chamalie Jirasinghe, Sandev Handy and Arun Welandawe-Prematilleke, with Subha Wijesiriwardena managing the event. Following is Sandev’s speech:

In the foreword to ‘The One Who Love You So,’ Arun talks about hearing that Article 365 and 365A were denied repeal by the Government when it was brought forward as a human rights action plan.

He says, that this was when he “finally became aware of the true experience of being queer in my country. As the phrase ‘culturally inappropriate’ became popular, I was realising that, on this island, to exist as a queer person is a political act. It was at this point that it became clear what I wanted to write about next.”

Seeing the play and reading those words made me think of what I can only describe as an ‘onslaught’ of things going wrong, or being made to go wrong in Sri Lanka. I think there is a pathology that is formed over generations when we are constantly forced to respond to the urgency of the moment in our practices, whether that be art or anything else.

To me it feels like we’ve become these super-structural beings, as in we are always living in relationship to these super structures imposed on us, whether that be violence, economics, history or our very existence being denied on the basis of identity. Our inclination it seems, is to either piggy-back on these super-structures, or mount a resistance against them.

I appreciate these modes of resistance, they are actions that emerge out of urgency, where the need to shout “stop killing people,” as we’ve often had to declare on the island – is an emergency of utmost importance. And I think it often informs the way we have approached art making. We are always mounting critiques or making work that attempts to reach a wide swath of the public and educate them and point out all the things that have just gone wrong.

When I say this, however, I don’t mean to deny the importance of these actions. I think they are an essential part of spurring eco-systems of change. But there is also an anxiety here for me, about what happens when we look back and realise that for decades the work we thought we were creating only as an urgent response at the time has become our modus operandi, a stuck state of being, the extent of our creative capacities and ultimately our imagination of humanity. What happens when we come to be only known by, and ultimately reduced to, the language of our resistance?

I wonder about this onslaught of things going wrong in Sri Lanka – and the art we make to rectify that wrong. I think about trauma. Or as Stephen Mitchell (psychoanalyst) calls it “the loss of relationality to self and to others. It is the loss of access to sources of vitality deep within oneself, sources that are brought to life in spontaneous and authentic relations with others, from families to strangers.”

This is precisely why Arun’s writing stayed with me.

In his foreword again he says, “But the play that came out of it isn’t a political piece, nor is it a screed against government; a work of large scope that aims to speak for the all voices of the community. It isn’t an angry play, either. There’s no villain, no revenge and no blame. It is a love story, and a rather simple one, at that. It is about two people who care deeply for each other but cannot give each other what they want or need, two people who are extremely verbose, able to engage in discourse that is wide-ranging and incisive, yet unable to communicate what they truly want.”

I think this is significant. To intentionally delve into what may seem like the infinitesimal obsessions of our experiences and that of those around us, into the tiny spaces where we are fully present. Where we can adopt a posture of refusal over just resistance. Where we can demand a kind of humanity that’s not in perpetual response to dehumanisation. Where we can discover complexity. Where we can craft in our work the particularities of something as universal as being loved more precisely.

I was reminded by the words of Mark Doty that I have held dearly. In his book of poetry, ‘Still Life with Oysters and Lemon,’ he says: “Intimacy, says the phenomenologist Gaston Bachelard, is the highest value. I resist this statement at first. What about artistic achievement, or moral courage, or heroism, or altruistic acts, or work in the cause of social change? What about wealth or accomplishment? And yet something about it rings true, finally—that what we want is to be brought into relationship, to be inside, within. Perhaps it’s true that nothing matters more to us than that.”

I feel the inverse is also true. Perhaps from this point of intimacy may emerge deeper critical insights, or work in the cause of social change, or altruistic acts, or heroism, or moral courage, or in the case of ‘The One Who Loves You So,’ artistic achievement.

Where in the words of Jack Halberstam (‘Queer Art of Failure’), making a difference happens “by thinking little thoughts and sharing them widely. In seeking to provoke, annoy, bother, irritate, and amuse; in chasing small projects, micropolitics, hunches, whims, fancies.” Thank you, Arun, for helping us discover these intimacies and through that very process, ourselves.

Pix by Shehan Gunasekara

(Sandev Handy is an artist, curator and art educator based in Sri Lanka, with a deep interest in the intersections of art and dialogue in urgent political climates. He is curious about the formations of power and violence—the ways in which they invisibly manoeuvre through the world, and how we might give them form. His sculptures, paintings, drawings, and publications have been shown in Sri Lanka, New Zealand and in the United States.)