Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Saturday, 7 April 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Mari Saito

New York Times: Kaori Masukodera remembers, barely, riding as a child with her mother, her hair teased and her lips bright red, in the family’s convertible to the beach. It was the last gasp of the 1980s, a time of Champagne, garish colours and bubbly disco dance-floor anthems, and the last time many people in Japan felt rich and ascendant.

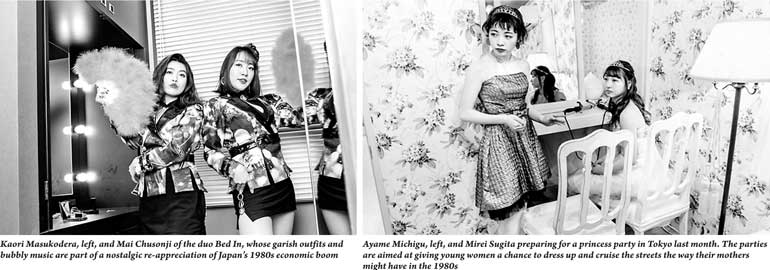

A so-called Lost Decade and many economically stagnant years later, the family’s convertible and beach vacations are long gone — but Masukodera is helping to bring the rest of Japan’s bubble era back. She performs in a pop-music duo called Bed In that borrows heavily from the keyboard lines, electric drums and power chords of the ’80s. They dress ’80s, too. The shoulder pads are big, the skirts are mini and the hues are Day-Glo when they aren’t just plain shiny.

“Until a few years ago, most people saw the bubble period as a negative legacy, and it was considered quite tacky,” said Masukodera, 32, wearing a tight blazer with jutting shoulder pads emblazoned with images of the Tokyo nightscape, paired with a miniskirt and gold jewellery. “That completely changed in the last few years,” she added. “Now people recognise it as kind of a cool period.”

Japan is in the midst of its most prosperous period in decades, as the economy cranks up and companies scramble for increasingly scarce workers. Still, for many people in Japan, that only underlines how far the country has fallen from the heights of the ’80s — wages are barely rising, the population is ageing and shrinking, and many feel that Japan’s best days are over.

That feeling has helped fuel nostalgia for the last time Japan was unquestionably on top of the world, joining a global re-appreciation for the ’80s in general.

Bed In’s fashion has become a fixture in local magazines. Similar ’80s attire now gets big play in glossy publications like the Japanese version of Vogue. A popular comedian who goes by the name Nora Hirano has shot to fame by mocking the era with her boxy power suits and brick-size mobile phone. Her outfit became a popular Halloween costume last year.

Then there is the Maharaja. A disco chain that ignited a boom in similar clubs more than 30 years ago, Maharaja clubs have reopened across Japan over the last five years to cater to nostalgic baby boomers, curious millennials and unwitting tourists.

Many young Japanese like to re-enact the era through wild limousine rides through Tokyo’s streets. Called princess parties by one event-planning company, they are aimed at giving otherwise frugal young women a chance to dress up and cruise the streets the way their mothers might have in another era.

“I wanted to do this one last time before I start working full time,” said Mirei Sugita, 20, as she curled her long hair and balanced a tiara on her head before heading out for the night. “We never do anything glamorous like this.”

That conspicuous consumption of the ’80s and the relative lack of it now underline the crucial differences between the two eras.

During the bubble years, men jockeyed to take women out on expensive dates and young people flooded ski resorts and other overseas travel destinations. In Tokyo, taxis were so hard to catch at night that people waved 10,000 yen bills — worth nearly $100 in today’s money — to get the drivers’ attention.

“It just feels like it was a more forgiving time,” said Mai Chusonji, 30, the other member of Bed In, recalling how her mother said she could barely remember the era because she was “out having too much fun.”

“There’s so much more pressure on young people now to avoid any mistakes, to make sure they’re stable,” Chusonji said.

The economic boom back then helped draw Japan’s women into the work force, a process that continues fitfully to this day. Bed In’s latest video nods to the era by parroting “trendy dramas,” a subgenre of TV programs of the bubble era that depicted the busy lives of young Japanese career women.

That era came to an abrupt end. Japan’s stock market crashed in 1990, and property prices plummeted. The period that followed is often called the Lost Decade, as Japan grappled with falling prices, slow growth and burdensome debt.

Japanese households now spend less of their disposable income than they did in the ’80s, in part because of stagnant wages and worries about the future. The government has struggled to get consumers to open their wallets. Last year, the government introduced “Premium Friday,” a program that encourages companies to let workers leave early one Friday a month so they have extra time to shop and contribute to the economy.

A 2017 survey by Dai-ichi Life Research Institute, a research group affiliated with a life insurance company, found that a majority of young people shy away from spending because they are concerned about the future. About four-fifths of people in their 20s said they wanted a stable life with a predictable future, something that has become harder to find in a country where wages are not growing and large numbers of people work under temporary contracts.

“Young people today feel anxious because they live in unstable times,” said Yohei Harada, who leads a team of researchers that focuses on youth culture at the advertising agency Hakuhodo. “That’s why there are more people searching for stability and civil servant jobs have become so popular.”

A group of high schoolers captured national attention last year when they channelled some bubble era confidence into this more timid time. Raiding thrift stores and their parents’ closets, 40 high school girls found enough power suits to win second place in a national dance competition set to the 1985 disco hit ‘Dancing Hero (Eat You Up)’. The video has been viewed more than 50 million times. “I feel like back then, people weren’t afraid to be noticed,” said one dancer, Nanako Meguro, 18, who recently graduated from Tomioka High School in Osaka, about 250 miles southwest of Tokyo. “They wanted to be No. 1. I think that compared to people nowadays, everyone seemed to have a lot more confidence.”

Pix courtesy Ko Sasaki for The New York Times