Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday, 13 February 2021 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Shailendree Wickrama Adittiya

The question of what constitutes art comes in various forms and different approaches are taken to answer this seemingly simple question. However, the arguments made for either side of the question are of more value than the conclusion one arrives at.

The question of what constitutes art comes in various forms and different approaches are taken to answer this seemingly simple question. However, the arguments made for either side of the question are of more value than the conclusion one arrives at.

When faced with this particular question, craftsman Gayan Sathyajith Karunarathne said everything is art. The path he took to arrive at this answer delves into history, art, mathematics, physics, and so many other elements. It makes one realise that the knowledge or interests of a craftsman is never limited to their particular craft but goes beyond it to other forms of art as well as other fields of study.

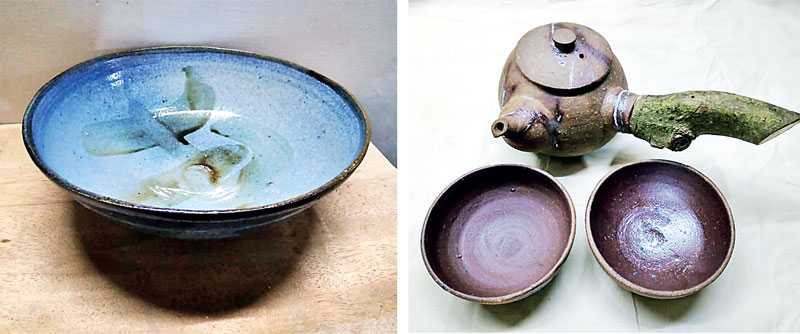

However, Karunarathne also managed to tie various components and subjects like mathematical formula, proportions, chemical reactions, and technique to the bowl he creates out of clay on a pottery wheel.

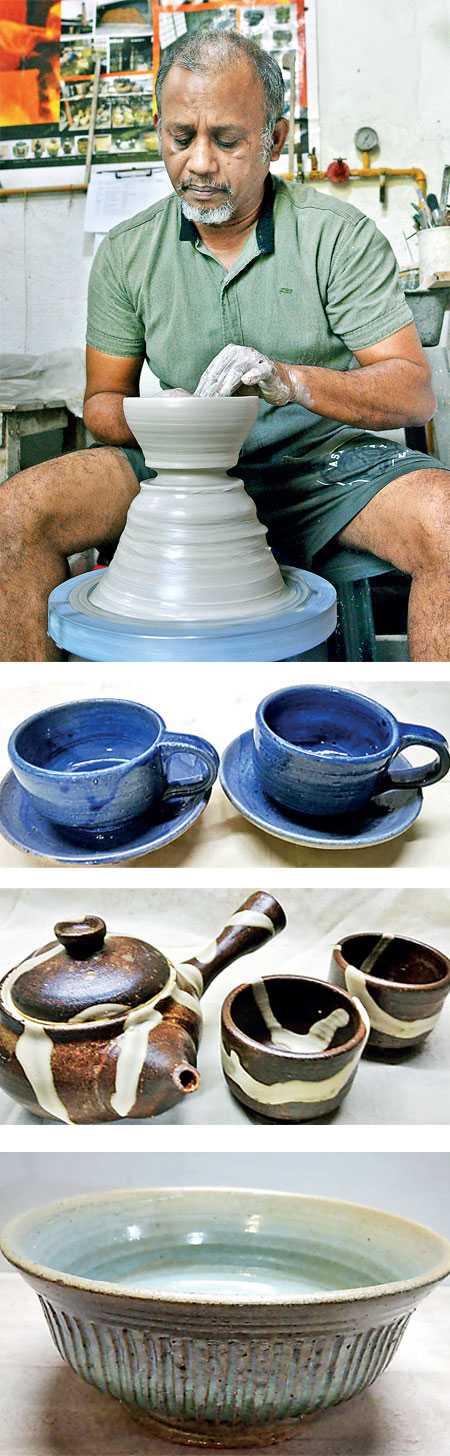

The Clay Studio’s Handmade Ceramics are created at Karunarathne’s place of residence, in a small studio adjacent to his home. He explained that he designed the kiln that stands in the centre of the studio and is a vital tool in the process of making ceramic products. A dialogue is carried out between the craftsman and the kiln, Karunarathne explained, when breathing life into creations.

Acquiring knowledge

The knowledge required to design a kiln comes from the one-year course he followed in Japan. Before Japan came a degree in sculpture and ceramics at the University of Visual and Performance Arts. “With the completion of the degree, I got the opportunity to go to Japan on a Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) scholarship, which was supported by Nagoya University of Art, JICA and a few other private companies,” Karunarathne said.

The course was an opportunity to also study the most advanced level of ceramics in Japan, which focused on both industrial ceramics and ceramic art.

Karunarathne returned to Sri Lanka in 2001 and joined the Vibavi Academy of Fine Arts. In 2004, while working at the academy, Dr. Takashima Hiro, who Karunarathne described as the sensei who taught him in Japan, travelled to Sri Lanka.

Hiro was here as a volunteer at the School of Design attached to the Architecture Faculty of the Moratuwa University. “He travelled here to start a ceramics course and selected me as his counterpart and I joined as a visiting lecturer,” the potter said, explaining that his other teacher, Prof. Akahiko Yanagihara, also travelled to Sri Lanka. While the former focuses on ceramic chemistry, the latter is a professor in ceramic design.

His first teacher, however, is Hiroki Asapura, a Japanese volunteer who came to Sri Lanka and taught the craftsman how to use ceramics as a tool without fear in 1999/2000.

In 2008, Karunarathne received the Bunka Award from the Japan Sri Lanka Friendship Cultural Fund (JSFCF) for special achievement in pottery and ceramics.

Karunarathne went on to spend the years leading to 2010 as a visiting lecturer, as well as an advisor to public and private organisations. This included the National Design Centre and Small Industries Development Department. “In addition to this, I lent my support to private sector entrepreneurs on issues with kilns and kiln manufacturing as well as providing technical advisory,” he explained.

During his time at the Vibavi Academy of Fine Arts, Karunarathne mainly worked on artistic ceramics, where aesthetic value was key. In order to research the topic of using clay and fire to create an artwork, exhibitions were held every three months in leading galleries in the island. “This was a great experience, especially for university students, and it created discourse on how to use a consumer product as a piece of art in Sri Lanka,” Karunarathne said.

However, he then had to decide between going forward with exhibitions or looking into production. This led to the establishment of his pottery studio four years ago.

Describing the products created, Karunarathne said, “What we attempted was an eco-friendly object for a sustainable society with handmade products and minimal machine use rather than machine-produced, industrial products.”

Locally-sourced materials, unique designs

He explained that 98% locally sourced raw materials are used in the studio, including the best clay and chemicals found in Sri Lanka. The materials used are non-toxic and least harmful to the human body. He also minimises carbon dioxide production by reducing the use of machinery. Only the kiln emits emissions.

While these factors make Karunarathne’s products stand out, he also ensures the designs are unique, with a very small number produced of each design. He described them as designer products, which no one can replicate.

Given his educational background, the influence of both Sri Lanka and Japan can be seen in his products and methods. “I mainly follow our traditional techniques, especially in design, looking at how they developed a body and so on. I also use 100% of the knowledge I acquired in Japan,” he said.

Despite the industry not developing in Sri Lanka, the country has strong designs and good products. He explained that a pot, for instance, is a sustainable design. When making his own creations, Karunarathne incorporates the good elements of these designs as well as technical aspects like reinforcement and decorations.

“Technology-wise, I mainly use Japanese technology and I am used to it. In Sri Lanka, craftsmen have a lot of clay on the wheel when making products but in Europe, they take enough clay for one product at a time,” he explained.

While the studio was built in 2018, renovations were done in January to expand the space used by those who come to him for training in the art.

“My expectation was to have a studio at a different location so that it is a training centre with an experience for tourists,” he said, explaining that the concept aimed at sharing knowledge with others. While these plans were put on hold due to financial constraints, Karunarathne said he plans to revisit them in the future.

Industry changes and challenges

Having been part of the industry since the early 2000s, Karunarathne was able to comment on the changes seen over the years. “Since 2001, we see a drop and it is difficult to pinpoint a reason or cause. There are several contributing factors like a social and political impact,” he said.

Despite this, however, there is a certain appreciation for arts among certain circles in the country. A lack of production and artists is an issue, however. There was a need for the development of individual potters in the country, Karunarathne said.

One of the main reasons for the current state of the industry is the investment one must make in order to start production. Expenses include buying equipment like wheels and kilns. Creating a market can also seem like a challenge, but Karunarathne was confident when saying that this was possible.

“When you are rich with ideas, you can change designs as you want. However, the issue with most people in the industry is that they make a mould and then keep creating the same product,” Karunarathne said. He explained that mass-production of this nature allowed manufacturers to maintain low prices.

On the other hand, Karunaratne’s prices are higher and he admits this. However, the pricing is justified considering the effort, skills, knowledge and talent that goes into creating unique products from clay.

“The clientele appreciates this and never bargains with me. The reason for this is that they know about aesthetics, ceramics, and art,” he explained. Price is a factor that plays a key role in purchasing decisions, however, but Karunarathne has been successful in creating a demand for his work.

At present, his products can be found at the Good Market, leading stores in Colombo, Pendi, and Milk and Honey Cafe. He also supplies to private clients like interior designers and small-scale traders.

“I have come to a point where I find it difficult to fulfil all my orders. This is something I am proud of because this is for the local market,” he added.

As is inevitable with any discussion about the arts, Karunarathne touched on the topic of society’s perception of the arts and those making a living out of any form of art.

“One belief is that you cannot make a living by being an artist. This is an absolute lie. Not only an artist, but in any sector, if you do it genuinely and honestly, there is no reason why you cannot live off it,” he said, adding that the extent to which people need arts is only felt with the loss of an artist.

Creating and teaching

With the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting movement restrictions, Karunarathne finds more opportunities and time to create. While he spends more of his free time in his studio, which is attached to his place of residence, Karunarathne is also a teacher.

“Teaching was what I most liked from the beginning. I wanted to share the knowledge I gained. There is a reason for this,” he said, explaining that when he began ceramics, no one helped him besides a select few, with some even holding back information or knowledge on techniques and processes.

Those who did help Karunarathne include Vineetha Seneviratne, who was attached to the Department of Industries, as well as Ranjith Weerasinghe, a designer, Chandraguptha Thenuwara, and Monty Senarath Colombage, who helped him when he first started the studio.

“More recently, the Good Market organisation has supported me a lot, with Achala Samaradivakara’s dedication allowing me to join Good market and create a good client base,” he added.

He also receives the support of his daughter, who helps with the marketing aspects of the venture, as well as his wife, who also studied similar subjects at university, and is good at pottery as well.

While he receives support with The Clay Studio, one issue that should be focused on is the supply of raw material. “There are local suppliers but there are a few issues. One is that there are times when we cannot get pure raw materials and instead get slightly contaminated material,” he said, explaining that suppliers cannot process raw material properly as there are very few buyers.

“If the number of potters increases, suppliers can increase the quantity of prepared material,” Karunarathne added.

Purchasing and repairing equipment is also an issue, as parts for equipment like kilns have to be imported.

While these issues can pose serious challenges to a potter, Karunarathne is an optimist and says, “If you are determined, then these are not big problems.”

Pix by Shehan Gunasekara