Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Saturday, 3 February 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

When we landlubbers hear the words maritime archaeology, we immediately think of centuries-old shipwrecks, the remnants of a once glorious era of maritime trade rotting away on the seabed. According to Maritime Archaeologist, scuba diving instructor and underwater photographer Rasika Muthucumarana, however, there’s more to it than that.

Delivering a lecture for the Maritime Archaeology Unit of the Sri Lanka Central Cultural Fund recently, Muthucumarana highlighted the many aspects of the discipline that may not be apparent to those of us who have never ventured beyond the standard snorkelling hotspots around the island, safe and secure in our tightly held lifejackets.

So if it’s not just limited to shipwrecks, what else is there?

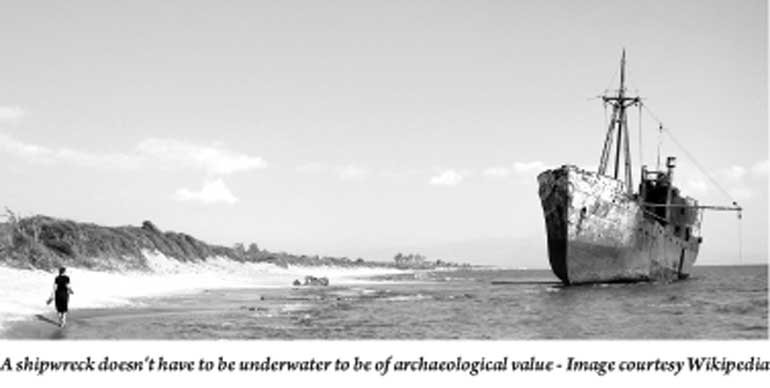

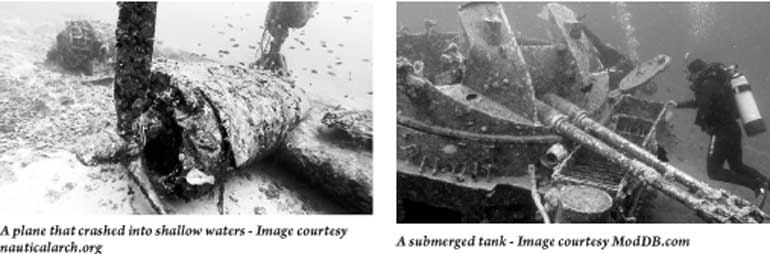

Apart from the obvious such as coins and other artefacts found in old shipwrecks, the field of maritime archaeology covers, among other things, airplanes, lighthouses and even battle tanks. Shipwrecks that are half-submerged or found on land are also counted.

The various types of cargo and related artefacts found any one of these sites have a lot of material value, which is why some people call it treasure, said Muthucumarana.

According to Muthucumarana, maritime archaeology is defined as the study of material remains that are a result of humans implementing maritime activities, such as ships, navigation, commerce, industries, trade, passengers and crew.

The UNESCO 2001 Convention for the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage, meanwhile, defines underwater cultural heritage as all traces of human existence having a cultural, historical or archaeological character which have been or totally underwater, periodically or continually, for at least 100 years such as sites, structures, buildings, artefacts and human remains, together with their archaeological or natural context Vessels, aircrafts, other vehicles or any part therefore, their cargo or other contents, together with their archaeological or natural context, and Objects of pre-historic character.

This means that pipelines and cables placed on the ocean bed is not considered archaeology, maritime or otherwise.

Although it technically isn’t considered archaeology or underwater cultural heritage, Muthucumarana, explaining the different facets of his field, shared with the audience pictures of a more recent shipwreck he’d found off Mullaitivu that contained bicycle handles and sacks of rice. The old beacon at the Urumalai light house, though, is very much a part of our maritime heritage, as is the Galle Fort which, apart from serving as a fortification of the maritime town contained within, also facilitated trade with the outside world.

Sri Lanka’s underwater heritage

Sri Lanka’s underwater heritage is not limited to the colonial era. According to Muthucumarana, potshards have been found dating as far back as the 2nd Century BC, in Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, with surprisingly detailed inscriptions of boats. The Godawaya Harbour goes back to the 1st Century AD.

“The custom duties from this port was given to the nearby temple, showing that it was a well organised harbour,” said Muthucumarana.

The Godawaya site is also home to the oldest wreck found in the Asia Pacific region. According to Muthucumarana, it’s a very fragile wooden wreck, located under 32m of water.

Stone pillars have been found in the area with inscriptions that have helped date the site. Excavation done at the temple has revealed an old stone anchor.

“In 2003 two divers found a strange spot full of pottery. In 2008 we dived there and found this magnificent site with a lot of potshards and a few complete pots. A study on the potshards revealed they were 2,000 years old,” said Muthucumarana.

The Godawaya site has been mired in controversy, but not over historical disputes, as one might expect.

“The last two years wasn’t a very good time for maritime archaeology. Because of some agreement reached between the Department of Archaeology and an American institute, the wreck was given to the American institute for research,” recalled Muthucmarana.

The matter was resolved recently, however, and Muthucumarana and his colleagues have started working on the site again.

“The shipwreck is very fragile. We still haven’t touched it; it requires a lot of expertise. We need to be very careful,” he said.

Preserving the country’s underwater heritage

The work carried out by maritime archaeologists isn’t restricted to diving and digging. Preserving the country’s underwater heritage is very much part of the job description.

For example, the iconic fishing boat, the one with big sail that used to be a frequent sight in Negombo, is fast disappearing. Muthucumarana is at the forefront of ongoing efforts to preserve that craft and knowhow.

“We need to protect that knowledge, because those kind of boats aren’t built anymore. Even if the shape of the boat has been retained, the modern incarnations of this boat are built using fiberglass. The culture that designed that boat is slipping away from us. We need to record such things and try to protect them,” he said.

Moving on to international examples of maritime archaeology, Muthucumarana spoke of shipwrecks found in coastal Europe, where tides raises questions on whether a semi-submerged wreck is considered terrestrial or underwater, depending on the time of day. He also used pictures of a wreck in the Pearl Harbour site to illustrate the point that sites of such socio-cultural import need to be preserved for future generations.

And there is a lot to preserve in Sri Lanka, such as the wooden wreck found in Trincomalee which still has its musket shots intact, and the Muhudu Maha Viharaya or the Great Sea Temple in Pothuvil which presents a bit of a challenge even to experience divers.

“Exploration is still underway. There are some parts of the old temple said to be still underwater. We haven’t found anything yet because the sea in front of the temple is very rough and hard to dive, with little visibility,” said Muthucumarana.

An incredible maritime archaeological find

One of the more incredible maritime archaeological finds of late is the stone bridge in Mankeni, Walachchenai. Stone pillars that the ancient bridge was built on top of have been found at regular intervals over the marshy lagoon, stretching to 236 meters, making it the longest on record.

When some villagers stumbled upon the stone pillars six years ago, they probably had no idea that they were looking at the remains of an old bridge that existed in the 3rd Century BC.

Muthucumarana and his team paid a visit to the site in 2012, where they discovered that the bridge stretched across the lagoon in close proximity to the shore, possibly connected to a path to Polonnaruwa, giving them the idea that it must’ve been part of a trade route.

“Last year we expanded our search. We recorded every pillar we could see, and the full length of the bridge comes to 236 metres. It’s the longest such bridge. The recorded is 60m.”

Signs pointing to ancient maritime activities

Even where actual physical evidence remains elusive, there are still signs pointing to the country’s ancient maritime activities.

“There are old temple murals from 100 to 150 years ago, from the south coast and the west coast depicting boats from ancient Sri Lanka. When the artist drew the boats on the murals at Shailabimbaramaya in Dodandoowa, he used a European sailing ship as a framework. The ship that carried the Sri Maha Bodhiya sapling to Sri Lanka was over 2,000 years old. The artist didn’t know what it would’ve looked like. So he based it on what he could see: the sailing ships near Galle,” explained Muthucumarana.

“There is one painting that shows Buddhist monks hovering in the clouds, and the clouds are shaped like a boat. These are some of the interesting things you come across when studying maritime archaeology,” he added.

Up north, Muthucumarana and his colleagues have explored and studied sites in Nilaweli and other areas in Trincomalee.

“The famous Bottomless Well in Nilaweli is a historic place. We did some diving there and discovered that it actually has a bottom,” he said.

World-renowned science-fiction author Sir Arthur C. Clarke who made Sri Lanka his home was also famous for his diving adventures. Though not a professional archaeologist, he was arguably a pioneer in the field, having discovered with his diving friends the well-known silver coin wreck of 1702 that he found near the light house in Kirinde.

Muthucumarana recalled that it was a “big event” that introduce maritime archaeology to the country.

“In the early 1960s, Clarke and his friends did a lot of diving off the cliff near the Konesvaram Temple in Trincomalee and found a lot of artefacts in the waters off the temple.”

Don’t get duped!

Decades later, Muthucmarana and his colleagues, too, have done their fair share of exploring in the area and located a number of artefacts from the old temple. If you ever decide to do some exploring here yourself, however, be sure not to get duped by local tour operators.

“Local divers sometimes place old statues that are not of any archaeological value and show them to foreign tourists. These new statues are ones thrown from the new temple.”

With the founding of the Maritime Archaeology Unit, the underwater heritage of Sri Lanka appears to be in good hands.

From its first training that carried out the Galle Harbour Exploration from 1993 to 1998 to its latest excavations, the Unit aims to train Sri Lankan archaeologists with assistance from foreign specialists.

The Unit was founded in 2001 with the Netherlands Cultural Fund, Central Cultural Fund, the Department of Archaeology, the Department of National Museums and the PGIAR.

For more information, visit mausrilanka.lk.