Thursday Jan 15, 2026

Thursday Jan 15, 2026

Saturday, 9 September 2017 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

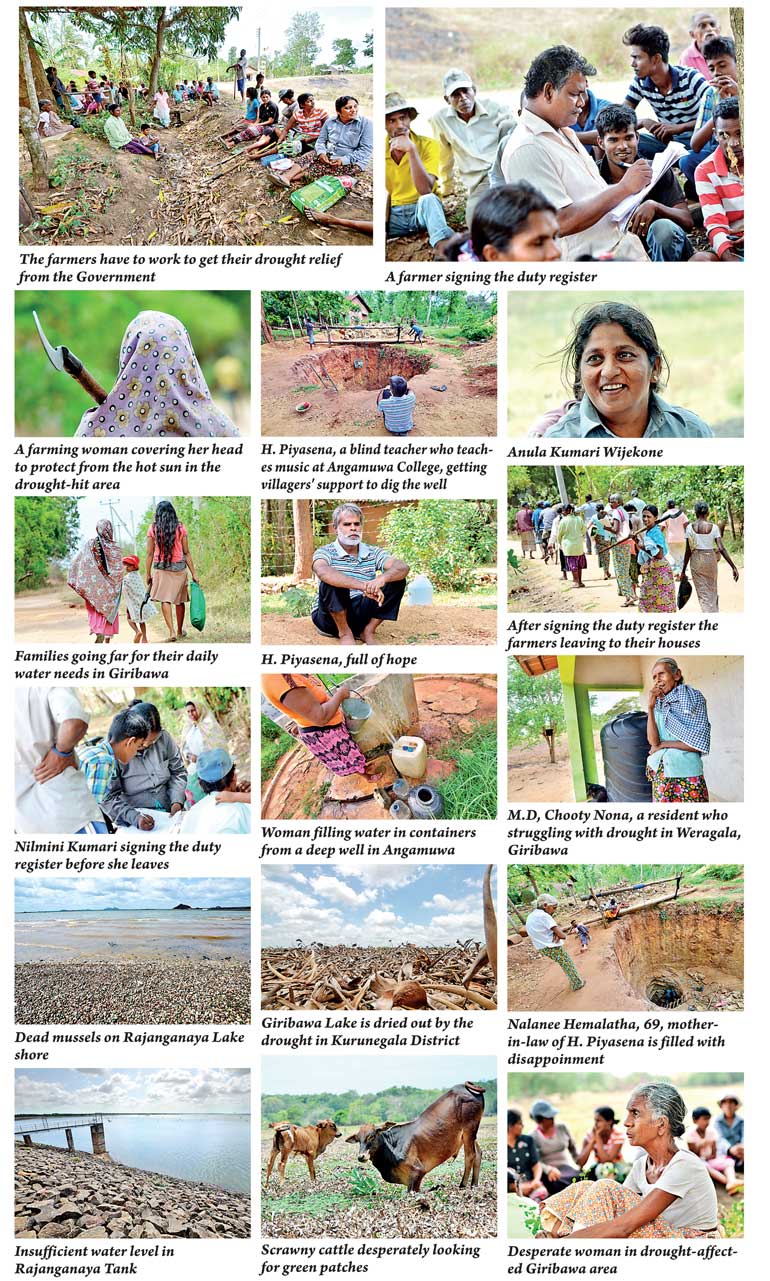

Farmers make up large communities of self-sufficient families in rural Sri Lanka. But deprived of their livelihood by the merciless drought, they are finding everyday life starkly difficult. Even with Government support, many contend that all they have little more than prayers to the rain gods.

Seemingly no one has answers to Sri Lanka’s ongoing drought, considered to be the worst in 40 years. On one side of a dusty road under scorching sun about 50 people sit, most holding their traditional farming implements. Some are very old while others are cradling babies. All of them have cloth wrapped around their heads to protect themselves against the unforgiving heat rising in waves around them.

Dry rations for work

These are residents of the Giribawa village in Rajanganaya, an area famous for its breadbasket accolades in Sri Lanka. The families here are mostly poor farmers who exist from one season to the next. A drought, especially one that has lasted as long as this one, has completely obliterated their livelihood and with it means for an income.

“We have been told that if we come here and work from 8 a.m. to 1.30 p.m. we will be given a bag of dry rations. But we have been weeding here for three days and not only have we not received the hand-out, we haven’t even seen any officials. We are supposed to wait here until a Government official comes here to take our signature but she has given the registry to someone else in the village,” said Nilmini Kumari (40).

The villagers complain that the relief efforts by the Government are inconsistent, badly organised and do not filter down to the worst-affected families. Used to being farmers for generations, they would normally have been busy at work maintaining paddy fields or maize, green gram and other crops. But the drought has put an end to those efforts, leaving them weeding the side of the road or tidying up their village in a food for work scheme that has been rolled out by the Government.

Passers-by cannot but feel sorry for the villagers, some of whom have to bring their ageing parents along to sit idly while they are engaged in the work. Used to toiling the land, they miss doing the work that has brought them an income and respect for decades. The changing weather patterns have altered their entire existence.

Officials acknowledge that the situation is not ideal but contend that the dry rations for work programme is a community-driven one and was formulated with the involvement of village representatives.

“We have not asked them bring old people but we acknowledge that it is better for them because otherwise there are all sorts of complaints when we distribute the dry ration packages. Some complain that they have to work while others sit at home, others say that they have to work harder because able-bodied people of another family have not done their share, and so on and so forth. We have to deal with all these issues,” points out Acting Divisional Secretary H.M. Herath.

Since the villagers are asked to do community work, the effort is overseen by a four-member committee, which also includes representatives of the village.

“We have done our best to establish a system that is inclusive and fair,” insists Anula Kumari Wijekoon (43), who is in charge of the register that volunteers have to sign before they are allowed the dry rations.

Water distribution

The Government has distributed makeshift water tanks to the villagers and set them up at strategic locations to give families access to clean water. Water bowsers trundle through the different villages every few days filling them up, but sometimes the water is not enough; at these times the villagers skip their baths and limit the water consumption to drinking and cooking.

“Many of the young farmers in the area have gone to nearby cities to work on construction sites; some have even gone to Colombo. They earn a little bit of money and send it home to their families. That’s how most of them get by now,” E.M. Jinasena (49) said, gesturing at the acres upon acres of paddy land wrapped around the village lying desolate under a cloudless sky.

“We don’t get water from the Rajangana tank. Traditionally we farm with rain water gathered in agri-wells and smaller tanks in this area. Each village has about three to four tanks and these used to be the main source of water. Since this drought has been going on for the past two to three years, most of these wells and tanks have dried up completely as well. We are hoping rains will return around mid-October but weather patterns have become so erratic it’s impossible to predict what will happen,” he added.

Bereft of all options, the villagers had gathered at the corner of the nearby tank and held a puja by boiling 100 pots of milk to local deity “Aiyanayake”. They hope the appeased gods will send rains faster and the region will return to prosperity.

Apart from the rituals associated with Buddhism, many people also believe in a variety of gods such as Minneriya Deiyo, Aiyanayaka Deiyo, Kalu Devatra and Bahirawa whose blessings are invoked for a variety of reasons. Blessings are invoked in the form of “yatika” to ensure their health, the protection of the weva bund and an adequate supply of water for cultivation.

The most noteworthy ceremony associated with the weva is “multi mangallaya” in which Aiyanayaka Deiyo’s blessings are sought. This ceremony is customarily performed by the village head after the rains when the weva is full. With no rains the people turn to the same god for salvation.

Hope amidst heat

While his neighbours are waiting for the heavens to deliver water, H. Piyasena has taken a different track. Having drafted the help of four friends, he is busy digging a well to provide water for his household. But the task has come at a huge price.

“We dug up the best coconut tree in our garden. That was a huge sacrifice because it was a tree that used to yield over a 100 coconuts every few weeks so now we have made a pledge not to give up till we find water. It would be a waste of a fantastic tree otherwise,” he said.

His mother-in-law Nalini Hemalatha (69) says the family was pushed to make a tough decision because a previous well dug by them hit granite and even explosives thrown down the deep hole could not crack the stone.

Thousands of others would understand and even approve of Piyasena’s courage. At once deeply independent and pious, their greatest prayer is for rains to return.