Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Saturday, 25 November 2017 00:47 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

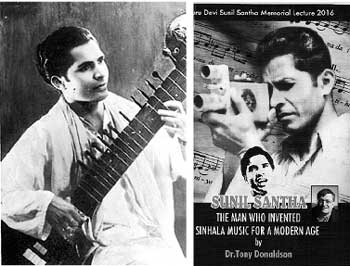

On the eve of the annual Sunil Santha Memorial Lecture two days ago, I was reminded of the inaugural lecture delivered last year by the Australian music researcher, Dr. Tony Donaldson. The thought-provoking talk given by him has been published as a booklet by the Sunil Santha Samajaya along with the Sinhala version – translated by Dr. Ruvan Ekanayake, who himself has done a close study on Sunil Santha’s music.

On the eve of the annual Sunil Santha Memorial Lecture two days ago, I was reminded of the inaugural lecture delivered last year by the Australian music researcher, Dr. Tony Donaldson. The thought-provoking talk given by him has been published as a booklet by the Sunil Santha Samajaya along with the Sinhala version – translated by Dr. Ruvan Ekanayake, who himself has done a close study on Sunil Santha’s music.

Tony D had been in Sri Lanka in 1996 for his doctoral research on a Graduate Scholarship awarded by the Monash University. It was while doing his study on the rituals and music in the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy that he had come across Sunil Santha’s songs. By then he had completed a Post-Graduate Diploma in Music Performance and Teaching.

Introducing Sunil Santha as “the innovator of a new form of Sinhala music for a modern age”, his talk was divided into two parts. He called the first part “The battle of Sinhala-Sri Lankan music” highlighting the different opinions among those who studied music in India as to how national or indigenous music should be developed.

He identified three groups: First was those who returned from India “with a grand vision to develop music in Sri Lanka based only on Indian classical raga music”. He identifies Professor Sarachchandra and Lionel Edirisinghe as two key men in this group. The second group led by W.B. Makuloluwa stood for Sinhala folk music. The third group comprised the two composers Ananda Samarakoon and Sunil Santha.

Elaborating on what Sunil Santha tried to achieve, Tony D says: “While Samarakoon developed a music language based mainly on Bengali music, Sunil Santha stood for something different. As a visionary, he stood against the practice of imitating Indian music in Sinhala songs but he really stirred and shook things up by going much further than any other composer by abandoning Indian music in his songs and to begin a search for an indigenous music suitable for this country. This was a bold step for the 1940s.”

Tony D then deals with the attitude of Radio Ceylon in the 1950s which, according to him, came to be controlled by “a powerful group of Indian ideologues”. He adds that Sunil Santha stood alone against the Indian ideologues which later cost him dearly as they set out to cripple him. “He was the first composer to breathe new life into Sinhala music for a modern age,” he says.

Tony D’s reference to ‘inventors’ in different aspects of Sri Lankan arts is interesting reading. While he recognises Sunil Santha as the inventor of a new form of Sinhala music in the 1940s, he refers to Lester James Peries (new artistic Sinhala cinema in the 1950s), paintings of Justin Deraniyagala, Harry Pieris and Richard Gabriel “which changed forever our perceptions of the landscapes, seascapes and people of this country”, brilliant cartoons of Aubrey Collette, “who teamed up in the 1950s with Tarzie Vittachi to fill an entire page every weekend in The Sunday Observer with Vittachi writing a searing piece on the week’s political events illustrated with Collette’s cartoons, and thousands of readers laughed their heads off on Sundays.”

“What distinguishes each as a genius is that they were not imitators but innovators. They breathed new life into their art and into the very soul of this country. There is something genuine and lasting about their work and that is why their names are remembered today,” he stresses.

He then discusses how Sunil Santha found a natural and legitimate way to invent a new type of Sinhala music for a modern age.

“He didn’t do it alone. Sunil Santha built around his music a collective ecology of talent by bringing together the best poets, musicians and singers in this country. This ecology of talent included poets such as Rapiyel Tennakoon, Gunapala Senadheera, Hubert Dissanayake, Fr Jayakody and Arisen Ahubudu. It included musicians such as the drummer Sarathsena; the  violinists Percy Wijewardena, Albert Perera (later Pandit Amaradeva), M.K. Rocksamy and Sony Perera, the cellist Alfred Corea, the flutist M.W. peiris, the guitarist Mervyn Wijewardena, and the brilliant Hawaiian slide guitar player Patrick Denipitiya, who had been a student in Sunil Santha’s music classes in 1952.

violinists Percy Wijewardena, Albert Perera (later Pandit Amaradeva), M.K. Rocksamy and Sony Perera, the cellist Alfred Corea, the flutist M.W. peiris, the guitarist Mervyn Wijewardena, and the brilliant Hawaiian slide guitar player Patrick Denipitiya, who had been a student in Sunil Santha’s music classes in 1952.

“The ecology of talent also included some of the finest singers in the country including Ivor Dennis, Narada Dissasekera, Rohitha Wijesoriya, Victor Ratnayake, Visharada Nalini Ranasinghe and Amitha Dalugama. There are also the singers who sang the film songs Sunil composed for ‘Rekava’ in 1956 and ‘Sandesaya’ in 1959, including Lata and Dharmadasa Walpola, Thilakasiri Fernando, Sisira Senaratne, Indrani Wijayabandara, Mohideen Beaig, Sydney Attygala and H.R. Jothipala. These are just a few names – there are many more.”

Tony D goes on to say that when you look back at the great poets, musicians and singers involved in his music since the 1940s, it reads like a Who’s Who of Sri Lankan music. “There are few composers in this country (if any) who can claim to have had that kind of ecology of talent involved in their music over the past seventy years, and that says something about how important Sunil Santha has been to the development of music in this country since World War 2.”

Part 2 of the talk is titled “Out of the shadow world: Towards an understanding on Sunil Santha’s music” where he discusses Sunil Santha’s music in detail.

A ‘must’ read for everyone interested in the contribution to Sri Lankan music by musical great Sunil Santha.