Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 10 August 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

“Do not learn this trade no matter what the reason, learn to repair vehicles instead. That is better,” Ajith Ananda, 48 said, concluding his chat. I had no response to give him. His body was wiry to the point of thinness, his speech

|

Ajith Ananda |

|

Sunil Premawansa |

direct. I asked permission to take his picture, unsure of the response, but he complied readily enough. I met him on my journey to find cinnamon peelers, which began at dawn and took us to the village of Karandeniya.

My guide was a local, so he knew the village well. As we approached, cinnamon plants were aplenty in the surrounding areas. Some had grown naturally over the years while others had been intentionally planted. Thanks to my guide’s expertise it was easy to find cinnamon peelers, put them at ease and take pictures. Many of them responded to the attention, however fleeting, that we could give. In some places it was only possible to take photos because I was with my guide.

Sri Lanka is globally famous for the quality of its cinnamon. In fact it is the largest exporter of pure cinnamon in the world and it is one of the highest earning export crops the country possesses. For this reason, cinnamon is also deeply intertwined with Sri Lankan history and culture.

The cinnamon trade flourishes in the Galle and Matara regions but it remains a cottage industry, using minimal machinery but high levels of human diligence and meticulousness. In these areas it is common to find entire families engaged in the full production process of cinnamon – from plant to packet.

Cinnamon and the Dutch

Sri Lanka has been a trading hub from ancient times and spices were one of the key export items. During that time the Sinhala Kings had a monopoly on the cinnamon trade and exerted complete control. However, when the Portuguese arrived in Sri Lanka this control was broken and it was further loosened when the Dutch captured most of the coastal land.

This gave the Dutch the opportunity to start systematic farming of cinnamon, which eventually gave birth to large-scale cinnamon plantations. This growing cinnamon export was encouraged by the Dutch who saw a great opportunity to increase their share of the global cinnamon trade and earn well from the enterprise. Gradually the cinnamon monopoly once held by the Sinhala Kings shifted to the Dutch administration.

The Dutch kept a stranglehold on cinnamon production and export. Cinnamon plants were deemed property of the State and they established a State department to oversee the industry, which was headed by a Dutch national. The Dutch exerted much pressure on locals to increase the profitability of the cinnamon trade and started using the traditional caste system of the natives to aid them in expanding cinnamon cultivation.

Under the local caste system the trade of an individual is decided at birth. Children of farmers farmed, children of healers healed, children of fishermen fished. The Dutch learned to use the families that harvested cinnamon for the Sinhala Kings in the same way.

Extremely rigid and suppressive measures were introduced to coerce these people to work unceasingly. Their leaders were selected from within the same caste, partly to effectively control them, and rather than pay them in money the Dutch preferred to give them parcels of land for their services. The Dutch as the influential middle men of the cinnamon trade used their colossal profits to gain themselves higher positions of power and social status. The result was, from colonial times, two distinct groups of people – cinnamon plantation owners and cinnamon workers – emerged as part of larger society.

Harvesting to market

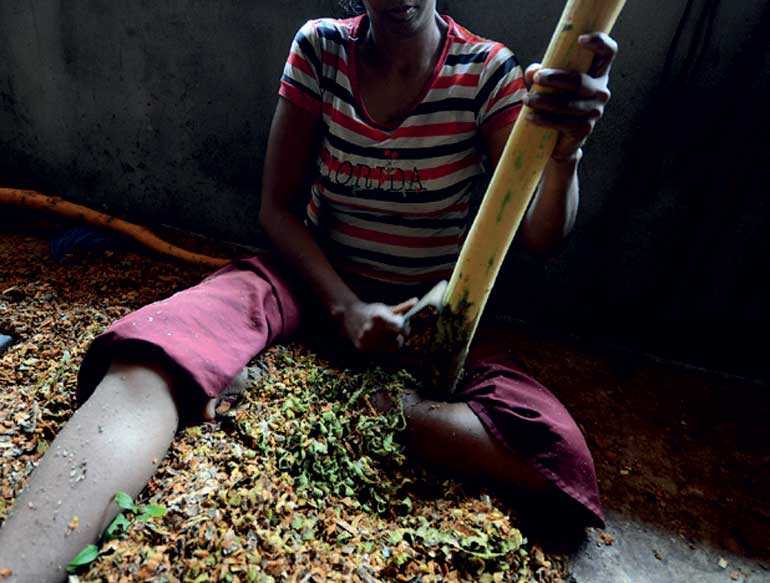

Cinnamon is usually harvested in groups of three people who are commonly referred to as a ‘kalliya’. Usually they start their work by collecting as many cinnamon branches as they can manage in one day and transporting it to a ‘wadiya,’ or a makeshift workshop area. A motorcycle or a hand tractor is used to do the transporting.

Once they arrive at the wadiya the outside bark is sliced off with a knife and rubbed with another stick to loosen the valuable cinnamon bark. The bark is then carefully dried and separate pieces are pushed together to create the standard cinnamon stick. These are then sliced to make up bunches of cinnamon sticks that are packaged and sold to wholesalers.

Then it’s time for cinnamon traders such as Sunil Premawansa, 59, to takeover. In his shop in Karandeniya, South Magala, he talks about the different grades of cinnamon.

“Most of these small time cinnamon peelers sell their cinnamon to minor traders. I purchase cinnamon from them. Most of the peelers don’t know how to properly identify different grades of cinnamon. There are about five or six grades of cinnamon. There are people who regularly sell to us and after we grade the cinnamon we sell to large companies in Colombo which export the cinnamon. They will even purchase shards of cinnamon leftover after making sticks.”

Social perceptions

Even though the cinnamon supply chain is complex and spread across a wide range of people, places and social situations, it makes little difference to the cinnamon peeler. Despite the vast amounts of money earned by cinnamon and the locations around the world it travels to, cinnamon provides little to the peelers. Their lot remains a struggle. During some months of the year when cinnamon is not available they work as day labourers to make ends meet.

Despite their history and economic contribution, cinnamon peelers still receive limited respect from society. Commonly referred to as low caste, the people who have provided a valuable commodity to the world are often treated as though they are worthless.

When we went to the home of a cinnamon peeler he agreed to pose for a photograph but his daughter refused, insisting that her father should not be identified by his profession. We acquiesced to her request.

But Ajith Ananda had no such qualms. He spoke while doing his work and appeared relieved to be sharing his discontent with the world.

“We are all people who have been cinnamon peelers for generations. We harvest cinnamon from our own lands as well as from rented plantations. This is cinnamon that belongs to the people who own this house. We are only given one-third of what we make into cinnamon sticks. If we make three kilos of cinnamon sticks they only give us one. That one kilo has to be divided between all three members of our ‘kalliya’. This means that we don’t even earn Rs. 1,500 per day. How can we live with such little money? We don’t have a stable market. One week they will give us Rs. 2,000 and then the price will suddenly drop to Rs. 1,700. So it’s unprofitable for us and the plantation owners.

“Even though we have done this job for generations we don’t know much about this. We don’t know where the cinnamon goes or where it is sold, or how much is earned by the final seller. We don’t know where in the world it goes. What we ask is for a proper market, if there is a regulated price then we know we will earn Rs. 2,000. There are times when we even do this for Rs. 500 because we don’t have any other skills, so how else will we earn? The only person who makes money from this is the rich businessmen. I always tell my children, ‘don’t learn this trade. At least learn to repair vehicles, at least learn to work in a garage. Don’t do this.’

“This trade is good for people who own hundreds of acres of cinnamon. Poor people will go and do backbreaking work because they don’t know of any other way to survive.”

He took a break and continued.

“When we go abroad, we cannot find work. There are no good jobs. We are told to drag garbage… So people continue to do this because they have no choice. Even though I have not taught this to my children, there are other children of cinnamon peelers poorer than I. Those children will follow their mothers and learn to do this. What other choice do they have?

“They will always languish in a sack.”