Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Saturday, 9 September 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

September is Literary Month. The State Literary Festival is held, State Awards are presented to the best publications of the year, seminars are conducted – all to promote the reading habit. The climax is the Colombo International Book Fair to be held in mid-September at the BMICH.

Looking back, we automatically got used to reading when we started going to school. In the lower classes we had to memorise verses from books. Having gone to the ‘Sinhala iskole’ away from Colombo (at Hanwella) until the fifth standard, I was exposed only to a few books starting with the ‘hodu potha’. At Ananda College, we had to read the books by well-known writers like Martin Wickremasinghe, Piyadasa Sirisena and W.A. de Silva and to the renowned Shakespeare works as we moved over to the higher classes when we did Sinhala and English literature.

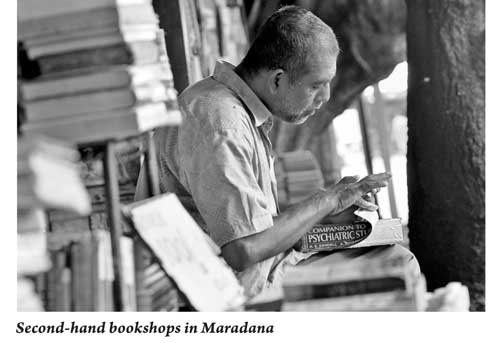

Walking from Ananda to the Maradana railway station, we passed a number of bookshops – some selling second-hand books in addition to new ones. Ariyadasa Bookshop and Wicks Book Depot were closest to Ananda. Closer to the station were G.A. Perera and P.K.W. Siriiwardena bookshops. On Maligakanda Road was Samayawardena bokshop, still running in the same place.

That was the time we were ardent Hindi filmgoers and we rarely missed reading two Indian publications in English – ‘Screen’ newspaper and ‘Filmfare’ magazine. We used to jump the tramcar and get to Pettah (the fare was 10 cents!) and pick these from Ananda Bhawan opposite Fort station on Norris Road. Close to it was McCallum Book Depot, a well-stocked bookshop. Further away was M.D. Gunasena Bookshop, dating back to 1913.

Tragic tales

Early this year when I met my fellow journalist in the Observer, E.C.T. Candappa in Melbourne, he gifted me a small book he had written titled ‘Adventures in Reading’.

Reading through the fascinating story of his reading habits since he was six years (he passed away mid-this year at 85), I was taken on a journey though bookshops in ‘our era’ in Colombo. Though I used to walk into Wicks Book Depot often to browse through second-hand books, I didn’t know the rather tragic story connected with the place till I read ECT’s book.

He writes: “It was a two-storeyed building. The proprietor was a tallish man, always dressed in shirt and sarong. He wore thick-lensed glasses and a grave expression. His shop was well stocked, with shelves going up from floor to ceiling. He knew where to find any book. I never heard his voice. He transacted all business in grave silence. We later learnt that he lived on the upper floor in what seemed to be a dinghy garret. Well, suddenly this most self-effacing man hit the headlines. He had hanged himself. The shop died with him. For months afterwards passers-by stood and gawked at the closed shop, speculating on what had led him to end it all.”

During my Lake House days in the latter part of 1950s and ’60s, I was in the habit of doing a stroll in Fort at lunch time. I used to walk in to the poshest shops –Cargills & Millers mainly – to browse through books and magazines. These two along with Caves, Apothecaries and Whittals had sections for books.

ECT relates yet another tragic story about Caves: “The proprietor who followed the first British one was a Mr. Fernando. He had all the flair of his predecessors. His entry was greeted with some fanfare by the press. His office, enclosed by glass, was large and elegant. From here he could see the entire establishment and indeed the whole establishment could see him. He appeared to be doing well but evidently his style of management had proved somewhat abrasive for some lower-rung employees. At the climax of one dispute, an employee entered his office and pointed a pistol at him. The boss covered his face with a Government gazette which he happened to be reading. The man fired and the owner died on the spot. The autopsy revealed that a staple from the gazette had lodged in his brain. The incident brought in more publicity but of an unwelcome sort.”

Home Library Club

A significant feature was that the two newspaper groups at the time – Lake House and Times of Ceylon had their own bookshops in their premises where the newspapers were printed. They were run as subsidiaries of the main company.

I didn’t realise that Lake House Bookshop was initially known as the Home Library Club until I read ECTC’s book. I have inherited a superb collection of hard cover books from my father. Dating back to the late 1930s they are a series of Home Library Club publications – a joint venture between Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd. (ANCL – Lake House) and an Indian group.

During the D.R. Wijewardene regime, ANCL had two subsidiaries in the same premises. One was Chitrafoto, a classy photographic studio situated in a strategic location at the corner opposite the Regal. In the basement floor was the bookshop. ECT had been visiting this ‘Club’ when he was at school.

He writes: “The most remarkable features of this place were the atmosphere and attitude. Though below street level, it filtered in sufficient light to brighten it. There were shelves with bright new books along the walls, and ladders to reach the higher levels. But best of all, there were plush, cushioned couches, where not only could the customers sit and browse through books at leisure, but they were encouraged to do so. The prime purpose, even with such noble merchandise, was not the mundane one of selling, but to encourage a literary pursuit, to read. A customer could take down a book, ‘taste’ it before purchasing it, or commence reading it in real earnest seated in comfort, leave it, return to complete it another day. This custom prevails in ‘Borders’, the excellent bookshop in Melbourne. Even though no money changes hands, no one minds because the primary purpose has been served – the book has been read.”

Later named Lake House Bookshop, it was moved to the new wing of the building on the right where there was more space. Later it moved to even bigger premises at the Lady Lochore Fund Building where it is presently located. The takeover of ANCL by the Government did not affect the bookshop which continued under the same name.

Makeen’s Bookshop was another popular place of the bygone era in Main Street, Pettah. Describing it as “another exceptionally congenial place”, ECT mentions that though very small compared to other bookstores, it stood out as an oasis in the bustling heart of Pettah for the sheer atmosphere of culture and refinement.

“The place had a wholesome smell of new books and the salesmen exuded gentility and courtesy. They never spoke unless spoken to, and then with great graciousness. The cashier, representing the coarse aspect of commerce, was discreetly hidden in an inner room. It proclaimed what the Home Library Club inferred in a sign I have never forgotten: ‘Come in and browse. Nothing compels you to buy’”, ECT writes.

ECT writes about the effort of a bold person, Gunapala Ranasinghe who had retired after serving in the Sri Lanka High Commission in London in the late 1950s, and started the Ceylon Readers’ Bookshop on the ground floor of Regent flats opposite Lake House. In what ECT thought was the smallest bookshop in Fort, it was housed in a triangular shaped partitioned-off section in the odd shaped foyer. The owner cultivated a one-to-one relationship and had “all the time in the world for a chin-wag”. He offered to order any magazines that patrons wished and gave catalogues to choose from. He sold them at prices lower than anywhere else.

ECT found Ranasinghe – a devout Buddhist and a great patriot – to be very agreeable company and his bookshop a pleasant retreat to visit during an idle hours. However, the venture didn’t last more than a decade.

As time went on the bigger bookshops like Gunasenas stared opening in the outstations. Some closed down while new ones were born. Obviously book publishing and distribution is a vibrant business bringing in good returns.