Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday, 2 June 2018 00:50 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Ramadan is the fourth pillar of Islam that gives the chance to cleanse one’s soul via piety and penance. Upon the first glimpse of the crescent moon, Muslims around the world start the ritual fast of 30 days, embarking on a spiritual journey to focus on being one’s best possible self. The month of Ramadan is of huge importance to Muslims as it gives the chance not only to show reverence to God but to escape from the monotonous pace of everyday life by abstaining from indulgences. From feeding the poor to sharing an ‘Iftar’ with family and friends, the spirit of Ramadan transcends the differences in religion, race and nationality. We bring you #ShareLoveThisRamadan with Aysha Maryam Cassim – a compilation of stories that talk about Ramadan from different perspectives and the values that bind people together through humility, solidarity and shared love

The joy of giving

Muslims observe Ramadan with manifestations of generosity. During the holy month, there is a special emphasis on the merits of giving and sharing. Those who observe are required to give Zakat – a charity – according to their means. By lending a helping hand, you’re spreading a message of love and community.

A few days ago, Bosath Tharuna Ekamuthuwa organised a dansala in Maradana to mark the Poson Full Moon Poya Day where the traditional Iftar breakfast ceremony was also held. Sinhalese youth served food to the Muslims, reflecting the brotherhood between the two communities. During a time when ethnic tensions are brewing, it’s a blessing to see people come together on the common grounds of kindness.

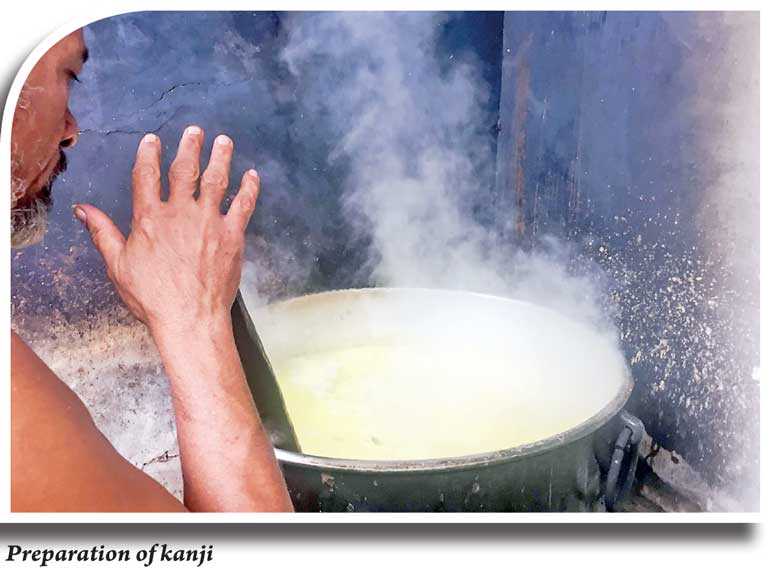

Kanji – Served with love and shared with everyone

Muslim cultures across the world share their special culinary delights particular to the month of fasting. In Sri Lanka, it’s the ‘Nombu Kanji’ that takes the centre of every Iftar table. Kanji – the bowl of porridge that is served with love and shared by everyone – is a favourite of many.

Kanji is a way of offering to feed the needy – be it travellers or less-privileged families – to ensure their hunger is satisfied after a long day’s fast. The porridge, which is a made out of rice, coconut and vegetables, keeps the stomach light and nourished.

A kanji has its variations and is usually served with a spicy accompaniment like ‘Thovayal’ – a paste made out of curry leaves, garlic and chili. For bodies that have been fasting for more than 12 hours, a bowl of kanji can be extremely comforting.

It’s a common sight during Ramadan to spot children in white skull caps and little buckets queuing up in front of the gates of the local mosque, waiting to collect their share of kanji.

We visited a Masjid in Vehera, Kurunegala to witness the preparation of kanji. The painstaking process begins in the morning and seems to last for hours until the kanji reaches its perfect creamy consistency. Usually, in every local village mosque, a cauldron of porridge is cooked by volunteers thanks to the generosity of patrons who donate money and rations to the mosque for the distribution of kanji.

Iftar at Masjid

Iftar – the occasion of breaking the fast – brings with it a sense of camaraderie and closeness with God. It’s a time when the family sits together and shares a meal. When the sun goes down, the fast is broken with some dates and a sip of water, in the same way Prophet Muhammad did, continuing a tradition of more than 1,400 years.

During Ramadan, most mosques organise Iftar programs for travellers and locals who come for evening prayers. Usually, they serve dates, water and kanji with some short-eats and fruits, all of which is free, sponsored by the benevolent souls from the Mahalla – the union of the mosque.

In addition to this, a bowl of fruits, yoghurt, a glass of faluda or nannaari (sarsaparilla drink) is served after the night prayers. Moreover, Muslim Majlis at universities organise programs that facilitate Sahar and Iftar for students residing in hostels and boarding places.

Milani fasts for the first time

“I like to experience things,” says Milani who, out of curiosity, thought it would be an interesting experiment to try Ramadan with her colleague Zumran. “Although I must admit that I missed my mandatory morning coffee, by evening I was impressed by the fact that I had the willpower to make it through a typical day at work with no food and water. After my morning meal, I worshipped and meditated, as same on other days. As a Buddhist I feel really good when I start the day with a moment of self-reflection.”

Sharing her impressions of her first day of fasting, Milani says that she felt like it was a prolonged period of ‘Nonagathaya’ where we shut our inner machinery for a few hours during a day. And to her surprise, she found that day to be more productive compared to a regular day at the office.

How the Bohras observe Ramadan

Sakina Shabbir joined us to talk about the Ramadan traditions of the Bohra community in Sri Lanka. The Bohras have traditions that are unique and different from those followed by a majority of Muslims during this month. Most of their rituals centre round the practices of their leader, His Holiness Syedna Mufaddal Saifuddin (TUS) in India.

The fixed Egyptian calendar is followed and Bohras do not wait for the sighting of the moon to start the 30-day fasting. It is a month of faith and fraternity and fasting. Breaking the fast ritually takes place in the masjid after the ‘Maghrib’ prayers have been observed. The fast is broken on only dates, tea and biscuits.

Amidst the countless Ramadan buffets, the Bhora Jaman holds a distinguished place with its simplicity and traditional taste. These meals are specially prepared to be palatable, yet keeping in mind the health of the community. Silat is the lesser-known but much-practiced Bohra habit of exchanging gifts during this Holy Month. As a means of patching up weakened relationships, building new ones and strengthening older bonds, the community, and especially its women, put a lot of thought and effort into what gifts they will share this month.

Ramadan in the east

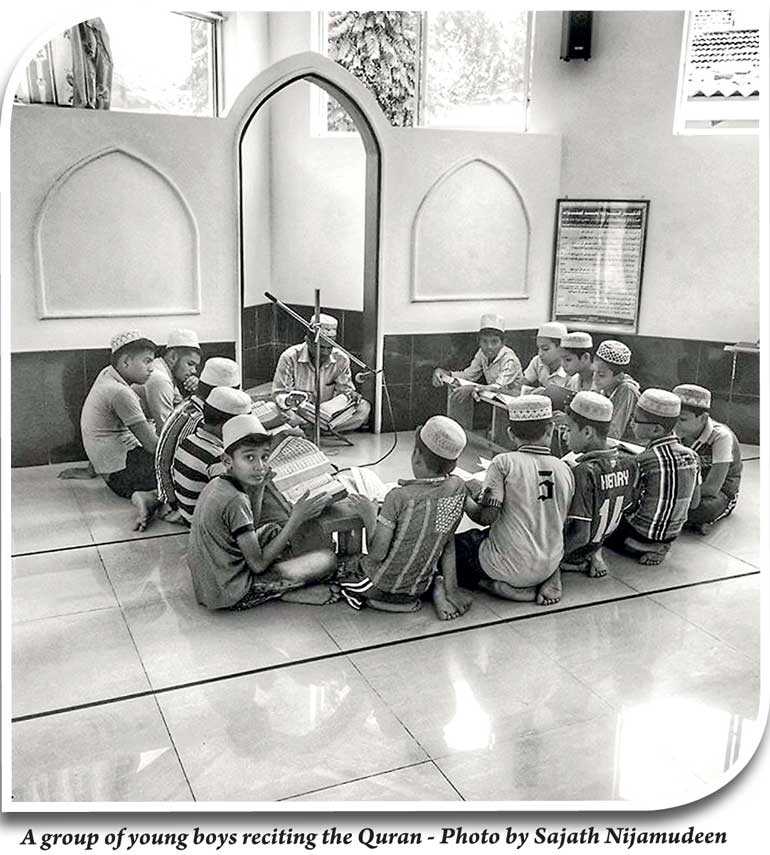

Sajath Nijamudeen, Public Relations Manager at Config, shared Ramadan stories from his hometown, Kattankudy.

“Ramadan in the east is a different experience. It’s an all-night affair, where you would see devotees attending night prayers and people gathering in wayside food stalls to have some short eats and Kahwa (Arabic coffee) over conversations. This continues for hours and ends with the call to morning prayer, around an hour-and-a-half before sunrise. Within the last 10 nights of Ramadan, especially, ‘Laylat al-Qadr’ – the night when the first verses of the Qur’an were revealed to Prophet Muhammad – streets are enlivened by vibrant lights on date palms and minarets of the masjids. It’s a beautiful sight at night. On Eid Day, we pray on the Kattankudy beach. There are carnivals and shopping fests on the festival day which brings joy to both young and old.” Whatever the religion we follow and however different our experiences and lives are, while fasting, someone else is probably feeling exactly the same way as we are. That is the beauty of Ramadan.

When the glorious month of Ramadan comes to an end with the sighting of the new moon, the observant feels rewarded with self-contentment.

“The day I fasted for the first time is the day I felt like I truly deserve some watalappam,” says Milani.

Of course, following a month grappling with hunger, thirst and self-restraint, the dawn of Eid begins with morning community prayers and a glorious feast of buriyani savans and watalappam that brings families and people of different faiths together!