Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Saturday, 7 March 2020 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Madushka Balasuriya

It has been a long 10 years, but, as Shehan Karunatilaka puts it, it’s also been “an action-packed 10 years”. This decade-long time stamp of course marks the years that have passed between Karunatilaka’s debut and sophomore novels – ‘Chinaman’ and ‘Chats with the Dead’.

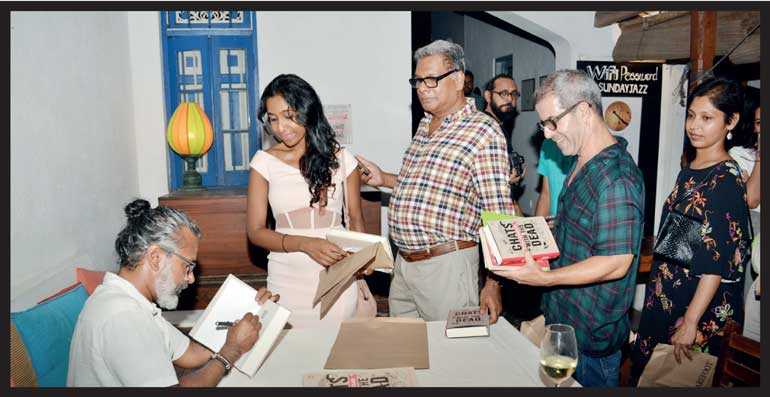

“I kind of did a wise and foolish thing after ‘Chinaman’ – I got married and I had children,” explains Karunatilaka in trademark self-deprecatory wit, of how he spent most of his time in between novels. He is speaking at moderated Q&A session at Barefoot in Colombo last week, promoting the launch of his new book.

“In those years in between I moved country twice. I did a couple of jobs,” he continues. “Actually when I finished it [‘Chinaman’], I fled to Singapore. Because the worst thing to do is to sit around and watch people read and comment on your book.”

That book of course is one of the most awarded novels in Sri Lankan history, with Karunatilaka winning the Gratiaen Prize, the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, and the Commonwealth Book Prize, as well as it being named the Second Best Cricket Book Ever by Wisden. That last award in particular has meant that in the years following the release of ‘Chinaman,’ most interviews and public appearances for Karunatilaka wouldn’t take long before veering onto the topic of cricket – much to his dismay.

“I once found myself in Seattle, the home of Kurt Cobain and Jimi Hendrix, talking about left arm leg spin,” Karunatilaka recounts. “I was told by my publisher that Americans don’t know much about cricket and so to keep it general.

I think the Colombo bubble has definitely been a theme, and I think if you’re writing in English you have to definitely accept that you’re a part of it. And knowing that prejudice, hopefully, makes a better book

“Then there was this old lady in the audience in Seattle who raised her hand, and I thought that she was going to ask about post-colonial literature or something. And she asks, ‘does Muralitharan chuck?’ I won’t tell you the answer that I gave but it was obviously complicated.”

“Then I found myself in Calcutta with [former Indian Cricket Captain] Sourav Ganguly in the belly of the Beast, talking about general cricket stuff, and then he threw me a grenade. We were talking about the state of cricket, and he asked me, ‘what’s happening with Sri Lankan cricket? Do you think that Sanga and Mahela are jealous of each other? So this alarmed me, and I thought the next book I write should be as far away from cricket as possible.”

And there in a nutshell is how Karunatilaka came to write a book about ghosts some 10 years later. Though the man himself probably does a better job explaining the exact nature of the book.

“It’s a black comedy about ghosts. It’s set in 1989. It’s about a dead war photographer – an atheist, a nihilist, a hedonist war photographer – who has travelled the island and seen carnage on an epic scale, and therefore believes that there cannot be a God and there cannot be any order to this universe, and much to his dismay ends up dead to find out that there is an afterlife – one where he also needs to look up the rules. And basically the story is about him solving his own murder.”

In an engaging and many times hilarious conversation with journalist and critic Adam Smyth, Karunatilaka opens up more about his journey after ‘Chinaman,’ writing children’s books, his influences, the stylistic narrative choices in his writing, and how “cowardice” was at the heart of his decision to base his latest story in 1989. Following are excerpts:

Adam Smyth: I know you have one particular favourite theme about the 10 years that have elapsed since the publication of ‘Chinaman,’ and that is things that you have either brilliantly predicted or things that, a cynic might say, have come to pass regardless. Would you like to run us through a couple of the hits?

Shehan Karunatilaka: I finished writing it in 2009, and I don’t know what Angelo Mathews and Nuwan Pradeep were doing at that time, but I sure as hell hadn’t heard of them. But then a few years later we had Nuwan Pradeep and Angelo Mathews opening the bowling, and someone sent me a pic saying ‘Pradeep Mathews opening the bowling for Sri Lanka in 2013’. And I had to claim that I had visions.

I mean we never had many left arm Chinaman bowlers, but then suddenly there’s a slew of them – you’ve got Lakshan Sandakan, you’ve got that guy [Kuldeep] Yadav in India – so Chinaman bowlers are around. Ambidextrous bowlers I’ve heard of, I’ve even seen reports of a double bound ball. And for those of you who don’t know, in ‘Chinaman’ a double bounce ball is one that bounces twice and spins twice, only Pradeep Mathew could bowl it – but then I saw on YouTube that someone else has done it.

And then of course the match-fixing, which I researched a bit. Talked to the ghost of Hansi Cronje. And the spot fixing, it was eerily similar to the way it was described in ‘Chinaman’. It was shady dudes with lots of cell phones and briefcases and things, in dingy apartments, fixing matches.

I found myself in Calcutta with [former Indian Cricket Captain] Sourav Ganguly in the belly of the Beast, talking about general cricket stuff, and then he threw me a grenade. We were talking about the state of cricket, and he asked me, ‘what’s happening with Sri Lankan cricket? Do you think that Sanga and Mahela are jealous of each other?’ So this alarmed me, and I thought the next book I write should be as far away from cricket as possible

AS: Joking aside about what you’ve been doing over the last 10 years, and the difficult second album, ‘Chats with the Dead’ is not in fact the second book. For anybody who doesn’t have small kids, the second book is in fact a kids’ book.

SK: Yes, ‘Please Don’t Put That In Your Mouth,’ for people who think my novels are little too lightweight and instead want something a little more highbrow and literary this is it.

I started a novel called ‘Devil Dance’ in 2015, and that was when my daughter was one year old. And one thing I was doing was that I was reading to my kids every evening, and some of the books like Dr. Seuss, Julia Donaldson, these are masterpieces. But some of them are pretty average and they sell much more than ‘Midnight’s Children’ or ‘Love in the Time of Cholera’. So I thought, forget spending six years crafting a literary novel which people will not read, when I can hammer this out. And the second book is being worked on now, it’s called ‘Where Shall I Poop?’

AS: So ‘Chats with the Dead’ is structurally, essentially, a murder mystery from the view point of the dead guy. Can we start with why the book is set in 1989?

SK: I think the main reason is cowardice, because I was thinking about the book and I knew I had to write a non-cricket book, and this was around 2012-2013, when in the aftermath of the war it was the rule of King Rajapaksa the first. During that time I was in Singapore and the only way I knew what was happening was through the internet.

And I suppose it was the battle of the documentaries. So on Channel 4 there was a documentary called ‘The Killing Fields’ which shows some shocking footage. Then the government put out a counter documentary, where they said, ‘yeah these people died but it wasn’t us, it was them’.

And it was the battle of the documentaries. But it occurred to me that if the dead could speak. If anyone could interview the dead, maybe then they could tell us who was pointing the guns at them and pulling the triggers.

But of course I was a bit nervous about writing about 2009, and I just didn't feel brave enough to write – and also, in 2013, to make sense of it. But I just realised that violence is not something limited to this century. We’ve had it all throughout our turbulent history.

I thought maybe I could write about ’83 – and someone should – but I just didn't feel qualified as a Sinhala Buddhist. But ’89 I remember, I was a teenager at that time, and it was the perfect storm, where you had the LTTE, you had the ITK fighting them, you had the JVP, the paramilitary, the Government death squads. And it just seemed all these dead bodies and unmarked graves were the perfect place to set a ghost story.

And also ’89, the good or bad thing about it, was that everyone was dead. The perpetrators, the victims obviously, so I felt safer. And also it was a different government in charge, and it was written about. So it was pure cowardice, because if I settled on ’89 I knew no one was going to take me to task about it, and yeah I can get away with it.

AS: So this book started out as a more overtly ghost story and folktale-related project. How did the book evolve into this?

SK: The first one the research was watching cricket and hanging out with drunks. This one I actually had to talk with dead people, but there weren’t many that were willing to be interviewed.

’89, the good or bad thing about it, was that everyone was dead. The perpetrators, the victims obviously, so I felt safer. And also it was a different government in charge, and it was written about. So it was pure cowardice, because if I settled on ’89 I knew no one was going to take me to task about it, and yeah I can get away with it

So I did some road trips – some of my road trip companions are here – where we got in cars and went to haunted houses. And it was fun trips, we went to see creepy places. And I also watched horror movies.

I have a go at romantic comedies for being formulaic, but horror movies are pretty formulaic. Pretty much every one dies apart from the final girl. And what found problematic was that when you write in the third person, you don’t see the ghost till like the third act. So the first two acts are just ‘is there something in this haunted house, etc., then someone dies, and then you see the ghost’. And in the best ones you don’t see the ghost.

But I had a problem with this because on the first page the ghost says ‘hi, I’m a ghost’ – so all that research it was fun, I wasted a good two years watching horror movies and visiting haunted houses. I haven’t seen a ghost myself, and I don’t particular want to. But I think if you haven’t seen it by now you’re not going to. But in the end it was all procrastination, I think that’s the lesson I give young writers - research is procrastination. It’s good up to a point, but just read two or three books and then write.

But yeah, I just realised that I had to invent an afterlife, one that was plausible. And I went to philosophy, to religion, but I guess no one knows what the afterlife looks like. So therefore I was able to invent it. So I spent a good few months building a world and rules of how ghosts work. And yeah, that took up three years!

AS: There is a hilarious four or five pages where it becomes clear that the afterlife is essentially a very badly run government department.

SK: I was thinking about the passport office, although it’s a lot better now. Also whenever I have ordered books on Amazon, sometimes it gets intercepted at the parcel office, and you’d have to put a day’s leave and collect that package. So that’s when I thought it’s plausible that the afterlife is like a passport office, where all these souls are not sure which counter to go to, which door to step through, which light to go with, whether they’re supposed to forget their past life or whether they’re supposed to pick it up and remember it. That chaos allowed for comedy as well. I realised that I’m not capable of writing proper horror, and I thought the absurdity of an afterlife like this, you could mine it for comedy and tragedy and I think it had both of them.

AS: Aside from the detective story, the novel is entirely written in the second person? Where everything is addressed to the protagonist. How did you decide on that?

SK: That’s of course a normal process. ‘Chinaman’ was written in the third person originally, but it’s only when I got a drunk to narrate it in the first person that I was able to tell tall stories, so the same process with this. I wrote it in the first person, but I just found it hard to separate his voice from mine and so on, and then I just looked at it technically. When the body dies, what survives death? What is the soul? Is it breath? And I just came to the conclusion that what survives is the voice in your head. And mine is in the second person, it’s always ‘you, you, you’. So when I took that on the book started moving forward, so it worked from a philosophical point of view but also stylistically. And he questions it, ‘does the voice belong to me, or are there ghosts whispering in my ear?’ And I’ve often thought that sometimes, are your thoughts your own? Why is that song in your head all morning? Is it cos you heard it on the radio? And all the bad ideas you have, do they come from you or is there someone whispering in your ear?

AS: From a novelist’s perspective, the central factor of the protagonist being gay is crucial to the progress of the book. Why did you choose to have a gay protagonist, was there a specific angle or motivation?

SK: Choose is a funny word. I didn’t choose for W.G. (the protagonist in ‘Chinaman’) to be drunk – he just was drunk. And likewise I didn’t choose for Mali to be gay. So you start from a lazy place, you start from real life. ’89 I thought, what if Richard De Zoysa’s ghost, and Rajini Thirianagama’s ghost and Rohana Wijeweera’s ghost were having an argument in the afterlife, that’s where I started it. But I mean obviously it’s a minefield, but that’s how I started out. But gradually as the drafts progressed the characters went away from that, but Mali was gay from the first draft – or a closeted gay man in the ’80s – and that sort of stuck around. He was very much like Richard De Zoysa in that he was a thespian, activist and so on, but then when I made him a war photographer he kind of took on a character of his own. But his sexuality remained the same, but I think it was useful because I was more interested in his relationships.

I was thinking about the passport office, although it’s a lot better now. Also whenever I have ordered books on Amazon, sometimes it gets intercepted at the parcel office, and you’d have to put a day’s leave and collect that package. So that’s when I thought it’s plausible that the afterlife is like a passport office, where all these souls are not sure which counter to go to

He had a girlfriend, but he also lived in the same house with his boyfriend. And he thought they didn’t know about each other. So with those relationships you get more of the human story. You’ve got the ‘did the JVP kill me, did the LTTE kill me, did the Government kill me?’ but also him resolving his relationships – because he didn’t treat them very well. And he didn’t treat his mother very well either, so to take out the sexuality I would’ve had to unravel those relationships. And I thought that was the only good thing that I kept from the ‘Devil Dance’ days.”

AS: Do you go to some extent to keep autobiography out of it? Have you purposely chosen an old man in ‘Chinaman,’ and then a gay war photographer in ‘Chats with the Dead,’ so as not to allow your own perceptions and attitude to lead you into stuff?

SK: Yeah that’s exactly it, especially when you’re writing in the first person. When it’s the same gender, same age group, they do end up sounding like you, and then you start injecting your own political opinions on to them. And that’s bad writing I think, then you’re writing a biography or a blog, when it should be all about character.

AS: Despite the fact it’s about a war photographer, almost all of the action occurs in Colombo. And Mali has a very love-hate relationship with the environment that he’s in – it facilitates certain aspects of his lifestyle, but also he’s clearly not comfortable with the people that surround him, let alone the people who employ him. Would you say you share the same attitude as him towards middle class Colombo during the war years?

SK: The first book was a Colombo bubble novel, and when I attempted it I was wary about talking about the war. This one, he’s in the Colombo bubble but he’s quite cynical about it. He feels guilty about his own privileged background and he looks around at people with scorn and disdain, and maybe that’s why he goes out these war zones to photograph things because he feels this – he’s not really Sinhala Buddhist – but sort of Sinhala middle class privilege guilt. Whereas the first one I avoided war, and the war crept in, this one I thought I should talk more about the things I didn’t want to talk about in ‘Chinaman,’ where the war has been overtly front and centre throughout.

So yeah I think the Colombo bubble has definitely been a theme, and I think if you’re writing in English you have to definitely accept that you’re a part of it. And knowing that prejudice, hopefully, makes a better book.

AS: You mention in this book, among a few other writers, George Saunders, Mohammed Hanif, Kurt Vonnegut, and Douglas Adams. Are these direct influences, literary models, literary debts you’re working off?

SK: Well, two of them are dead. I’d like to say they were my best friends and I spoke with them. Kurt Vonnegut and Douglas Adams informed the first book, and informed this one. Kurt Vonnegut’s my hero, and sadly the great man has passed away and I only have three more books of his that I haven’t read, so I’m rationing them slowly over the years.

But he pretty much writes the same book over and over again. It’s how about how we’re just a bunch of barbarian monkeys ruining this planet, and we’re all going to die. But it’s so hilarious the way he can, with humour, talk about the doom and gloom of the human condition.

And same to an extent with Douglas Adams, so I always kept them next to my writing desk. Hanif is my favourite South Asian writer – ‘Exploding Mangoes’ came out before ‘Chinaman,’ and I reread that many times. So I think I share a sensibility with him. George Saunders, a wonderfully talented writer whom I admire a lot, unfortunately he wrote a book about talking ghosts that won the Booker, when I was starting out on this. And I was like ‘damn, how am I going to top this?’ But I read George Saunders, and yeah, I cannot aspire to that level, so I thought he’s writing a very different book to me.

Pix by Shehan Gunasekara