Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Saturday, 10 February 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Madushka Balasuriya

“It was an examination of how we, in facing up to some of life’s greatest emotions – and I think sorrow is right up there – are more alike than not. In facing up to them and dealing with them, and overcoming them and moving on, how we’re so damn alike.”

As Siddharth Dasgupta sits down to speak with me about his latest book, the passion that was the driving force behind his latest collection of short stories – The Sacred Sorrow of Sparrows – Is clear as day.

It’s a weekday afternoon and, just a few hours after arriving from Galle, the Indian poet and novelist is chatting with me at the Shangri-la Colombo’s Kaema Sutra restaurant. He was down in the picturesque seaside town for the 2018 Galle Literary Festival, where he hosted two conversations on poetry and fiction, discussing his 2017 releases – the aforementioned Sacred Sorrow of Sparrows and his poetry collection, The Wanderlust Conspiracy.

He describes the former – “a universal examination of sorrow and melancholy as expressed through an ethnic prism of characters and cities” – as a “deeply personal and cathartic project,” while the latter is more carefree “fed by travel and movement, and the sense of having lived and breathed cities which I’ve remained close to.” Both however are a means of making sense of an ever more fractious world.

“The world is at a very strange place in time. You need to be politically aware, geopolitically aware,” he muses. “Where I live is in a pursuit and articulation of a certain beauty, a certain bliss, almost viewing a certain poetic sensuality as an antidote of what is going on at the moment.

“I’m scouring for books, I’m scouring for food with a certain sense of character. I’m hopefully engaged in conversation that lingers. Photography – black and white photography in particular. And anything again that is an antidote to the darkness.”

Fret not though, Dasgupta isn’t as morose as this write-up may possibly make him seem. He enjoys food, movies, and music, like the rest of us, and though it is his first time in Sri Lanka he has a select few friends that he enjoys his time with. He is also rather optimistic in his worldview.

Over the course of our conversation we embark on several topics, from the simple joys of discovering new and vibrant experiences, to the rise of ‘instapoets’ – the new breed of micro poetry taking over social media – to the refugee crisis in Europe. Throughout there is one overarching theme, the importance of education.

For Dasgupta, education is less about school and more about learning and understanding the human condition. The best way to do this, he suggests, is through travel. Having only recently relocated to his hometown of Pune in India – he hesitates to call it a ‘permanent’ move such is his wanderlust – travel, he believes, helps facilitate empathy in human beings. Something he decries is increasingly lacking in these troubled times where discourse veers tragically towards walls and borders.

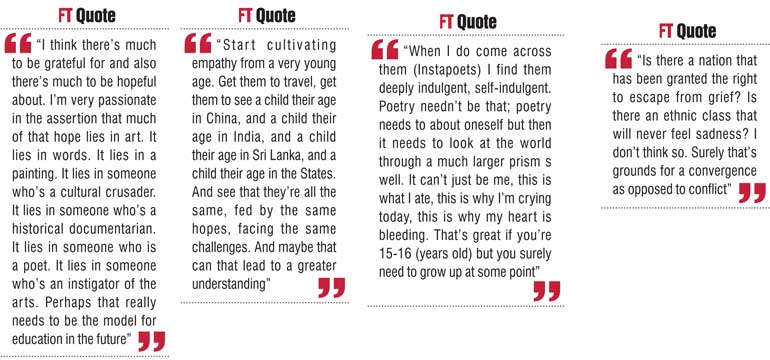

“That is the one way to start cultivating empathy from a very young age, get them to travel. Get them to see a child their age in China, and a child their age in India, and a child their age in Sri Lanka, and a child their age in the States. And see that they’re all the same, fed by the same hopes, facing the same challenges. And maybe that can that lead to a greater understanding.

“Is there a nation that has been granted the right to escape from grief? Is there an ethnic class that will never feel sadness? I don’t think so. Surely that’s grounds for a convergence as opposed to conflict,” he ponders.

Dasgupta pines for a world in which the ‘arts’ are valued as highly as more traditional livelihoods; in such a world, he proposes, empathy might more easily blossom.

“I think there’s much to be grateful for and also there’s much to be hopeful about. I’m very passionate in the assertion that much of that hope lies in art. It lies in words. It lies in a painting. It lies in someone who’s a cultural crusader. It lies in someone who’s a historical documentarian. It lies in someone who is a poet. It lies in someone who’s an instigator of the arts. Perhaps that really needs to be the model for education in the future.

“Can we channel whatever new avenues that have opened in the last few decades and feed those with people equipped to take on those roles, and not just be obsessed with a very methodological form of education, that is only very academic and completely, completely ignores a sense of human worth?”

This greater understanding of his even stretches to topics closer to his heart. Throughout our meeting I attempt to provoke a reaction – a soundbite, if you will – on something the world of poetry as a whole is divided on: micro-poetry.

“I really have a truthful belief in the notion that begrudging someone simply for being successful is a silly grudge to bear,” he responds when asked his thoughts on the popularity of those bite-sized quasi-philosophical musings that fill your feeds on Instagram and Facebook.

“Do I wish some of these people were making their living from something other than literature? Perhaps. But it’s not for me to judge, and it’s not for me to control.

“People are finding the words and the poetry and the literature that they’re comfortable with, and if they’re comfortable with micro-poetry and they’re comfortable with all of that, I mean good for them.” Unsatisfied with this response I prod him further for a soundbite, and finally he breaks – somewhat.

“But when I do come across them I find them deeply indulgent, self-indulgent. Poetry needn’t be that; poetry needs to about oneself but then it needs to look at the world through a much larger prism as well. It can’t just be me, this is what I ate, this is why I’m crying today, this is why my heart is bleeding. That’s great if you’re 15-16 (years old) but you surely need to grow up at some point,” he needles.

This final point however is also appended by a qualifier. “Let me anchor this by saying if it’s bringing the writer a certain joy then wonderful for them. Who am I to impede them? It’s easy consumption. I wouldn’t say it’s as unhealthy as fast food or soft drinks but it is what it is and also for readers who are taking something from that, wonderful.”

And in that Dasgupta perfectly illustrates the virtues of travel and being well read; even when discussing a subject in which he so clearly has such strong convictions he remains tactful as ever, something which we could all strive for a bit more in our lives.