Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday, 16 December 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

The saying goes “Better late than never”. Sixty-four years after Sir Ivor Jennings left Sri Lanka, his statue was unveiled at the Peradeniya campus last week in recognition of his pioneering efforts in ensuring that the country had a well-laid out residential university equipped with the best of teachers and students’ comforts at the halls of residence.

He should have been recognised in that fashion much earlier. Yet even at a late stage it’s nice to see his statue come up amidst the trees he watched growing up and the roads and paths he used to walk about clad in a short-sleeved checked shirt and a pair of tussore trousers with a walking stick in one hand, often smoking a cigarette.

Possibly the then undergrads who were fortunate to be there when Sir Ivor was Vice Chancellor feel the lapse more than others having appreciated and admired his efforts.

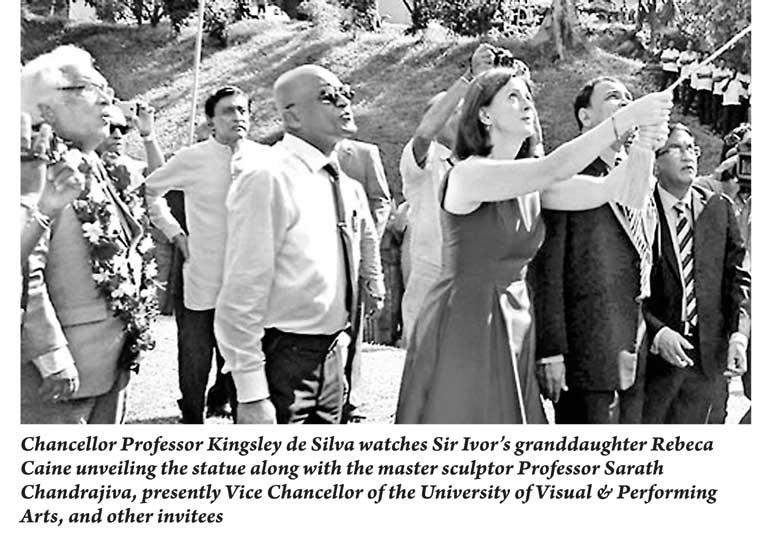

Chancellor Professor Kingsley de Silva who used to walk down for lectures from Marrs Hall passing Jayatilaka Hall where I was, would have recalled the good old days as he watched the opening ceremony. Along with the master sculptor Professor Sarath Chandrajiva, presently Vice Chancellor of the University of Visual & Performing Arts, and other invitees he watched Sir Ivor’s granddaughter Rebeca Caine unveiling the statue.

Year 2017 has been a momentous one for Peradeniya University. It marks the 75th anniversary on the University of Ceylon, first established in Colombo and then shifted to Peradeniya in 1952 when a few faculties like the medical and engineering faculties continued to be in Colombo until buildings and other facilities were completed in Peradeniya.

Peradeniya University also won international recognition this year as one of the ten most beautiful universities in the world. With the grown up flowering trees, it is now referred to as the ‘Garden University’.

Sir Ivor came in 1941 to succeed Dr Robert Marrs as the Principal of the University College with a directive by the British Government then administering the island, to lift the University College to the status of a University. The lawyer/university lecturer in law set about the task with much enthusiasm.

The setting up of a university had been accepted by the legislature and a debate had been going on as to its location. A ‘battle of the sites’ had begun.

Sir Ivor’s keenness is amply demonstrated in his autobiography, ‘The Road to Peradeniya’ where he recalls how he set about the task. Soon after his arrival in March 1941, on Good Friday he drove all by himself to survey the proposed site. He saw to it that the newspaper reporters were avoided.

He writes: “I drove along the Galaha road until I reached the plateau which we now call Convocation Hill. Climbing through the incipient jungle was no easy matter, and I knew not whether there were snakes around. Sitting on a tree trump on the bank of the Mahaweli Ganga, I spread Sir Patrick Abercrombie’s site plan before me. I began at last to see the magnificence of the scheme. There was no doubt about it, Mr. D.R. Wijewardene was right. This could be a great university. Next I drove up the Old Peradeniya Road so as to look down on the site. Finally, I crossed Peradeniya Bridge, climbed up the railway bridge, and walked along the Nanu-Oya. It is from that point, where the new Gampola Road is being driven through, that the finest view of the site may be obtained. In a few years’ time the view from the Nanu-Oya Bridge will be one of the most famous in the world.

“The scheme was of course magnificent and if the reader will follow my example 10 years later he will see it taking shape, though even in 1941 it could be visualised. Over there on Convocation Hill would be the Library, with the Arts Building stretching behind it. To the right of the Library, joining it to the Convocation Hall, would be the Administration Building raised on granite pillars like the Brazen Palace at Anuradhapura. On the extreme right would be the Convocation Hall to seat 1,750 persons. To the left and right would be Halls of Residence and other buildings. The whole would be framed in the tea-clad hills of Old Peradeniya, and above them the ‘patana’ of the Hantane Ridge. No university in the world would have such a setting.”

Before getting back to Colombo Sir Ivor visited the Peradeniya Gardens and observed what could be done with trees, shrubs and grass. He decided that landscaping of the Campus should be done on the same lines.

Before getting back to Colombo Sir Ivor visited the Peradeniya Gardens and observed what could be done with trees, shrubs and grass. He decided that landscaping of the Campus should be done on the same lines.

Back in Colombo, he consulted Sir Nigel Ball, Professor of Botany and both of them went and met the Curator of the Gardena, Parsons, who was willing to start the landscaping if money could be given. This was arranged and landscaping was done in two large sections.

“Especially notable is the beautiful valley of the Meda-Oya, sometimes called Abercrombie’s Dell. These sections give some idea of what the University Park would look like when the building operations are completed,” Sir Ivor wrote.

We have seen the fruits of his labour. As the pioneers at Peradeniya not only did we enjoy our stay but in our own small way we tried to build traditions, and form friendships which have lasted for many decades. Today we look back at the memorable years we spent there with great pleasure.

Sir Ivor who left to take up the post of Master of Trinity Hall, Cambridge sums up his mission in Sri Lanka thus: “I am in no way tied to Ceylon and I can leave when the spirit moves me. I can therefore back my judgement without fear of personal consequences and can concentrate on the main issue, that of providing the Island with the sort of university which her independent status requires and the intelligence and good humour of her people deserve. This of course not only, or even primarily, a problem of supporting the architects in the magnificent work which they are doing under great difficulties; it is also a problem of developing a tradition in the University itself, so as to make it a fraternity of ‘masters and scholars’, engaged in the advancement and dissemination of knowledge and the production of young men and women with personality and judgement.”

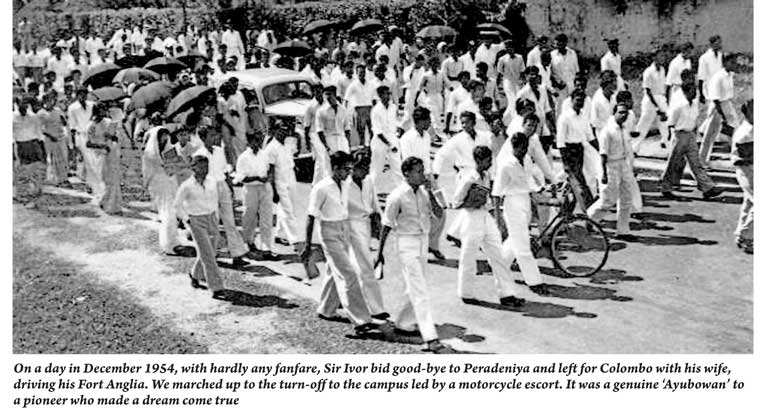

It was a day in December 1954. With hardly any fanfare Sir Ivor bid good-bye to Peradeniya and left for Colombo with his wife, driving his Fort Anglia. He was in one of his favourite short-sleeved checked shirts. We marched up to the turn-off to the campus led by a motorcycle escort. It was a genuine ‘Ayubowan’ to a pioneer who made a dream come true.