Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday, 9 February 2019 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Aysha Maryam Cassim

In the early ’70s, the Sri Lankan political landscape started changing, with violence becoming an integral part of society and politics – and with it Sri Lankan art lost its naïve innocence.

The early ’80s saw the worsening of ethnic conflict and the start of armed conflict of JVP and the LTTE with the State. During this tumultuous period, a younger generation of students who were witnessing all these changes emerged on the forefront in the early ’90s. They began to expand their thematic, taking a narrative turn in art and looking for a way to evoke their feelings by being responsive to the issues in the society.

‘The Days We Screamed’ was an exhibition curated by Jagath Weerasinghe to gather work by a generation of artists who gave a meaningful expression to the Sri Lankan political milieu in the late ’80s to early 2004. This exhibition was at the Theertha Red Dot Gallery in Borella from 26 January to 1 February.

The exhibited installations at the gallery mostly stemmed from the political context of the civil war between the Sinhalese and Tamil people in Sri Lanka. The art attempted at unfolding stories of human agony and also the inhumanity and barbarity that repressive regimes were capable of on their own people.

“Yes, we screamed those days, mostly out of fear, at times out of joy when the opposite side faced some loss. Lives were taken for granted, fallen numbers mattered much more than the saved lives for both sides. There were arguments, hate speech even among friends across the divide,” says Jagath whose series titled ‘Anxiety’ (1992) marked the turning point in the visual art scene in Sri Lanka. Jagath pointed at his work on the wall – the famous portrait of ‘Decapitated Heads’ – and tells me, “This not what you want to hang in your dining room. They are not here to please you. Contemporary art is a personification of people who created it. It is a craft rather than art. They try to convey a message. In this painting, I wanted to tell the world that ‘I have got enough guilt to start my own religion’. I had a major personality breakdown when I saw Tamils being murdered by my own community. I asked myself ‘how could we do this?’ I grew up with that guilt. Later, art became my new religion and the means to envision a change that I wanted to see in the society.”

“Those were the days we screamed, but nobody heard. But today everybody hears it. The Colombo skyline is changing with the unprecedented capitalist development and ensuing gentrification. Art is still being challenged and radicalised. I curated this exhibition for the occasion of Colomboscope 2019 – a contemporary and interdisciplinary arts festival which takes place in Sri Lanka.

“Colomboscope is a manifestation of what we did in the ’90s. What you see there has a history and we want people to know about it,” concluded Jagath.

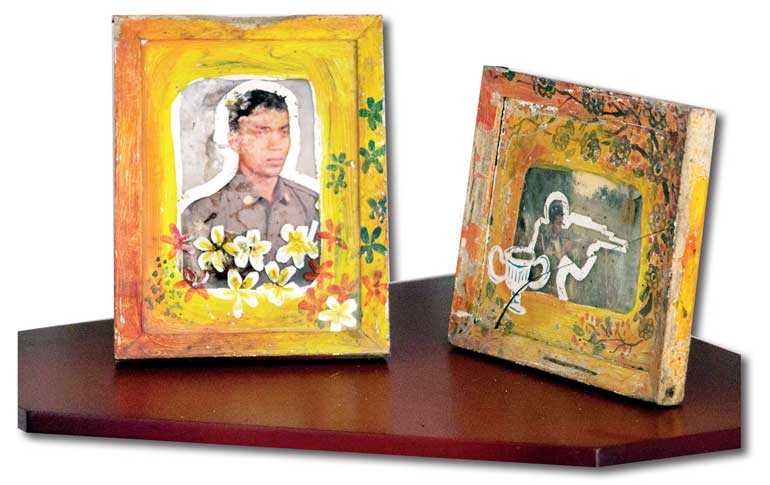

Pradeep Chandrasiri’s art reflects his personal experience in the political violence of 1987-1989. “Most of my work has been exhibited in spaces surrounded by remnants of war. In my installation, 13 panels hold 13 broken hands that are placed on 13 betel leaves – which are turned upside down as they do in ‘funeral houses’ indicating an unfortunate event. I was born on the 13th and this artwork symbolises my suffering and all the bad luck associated with the number”

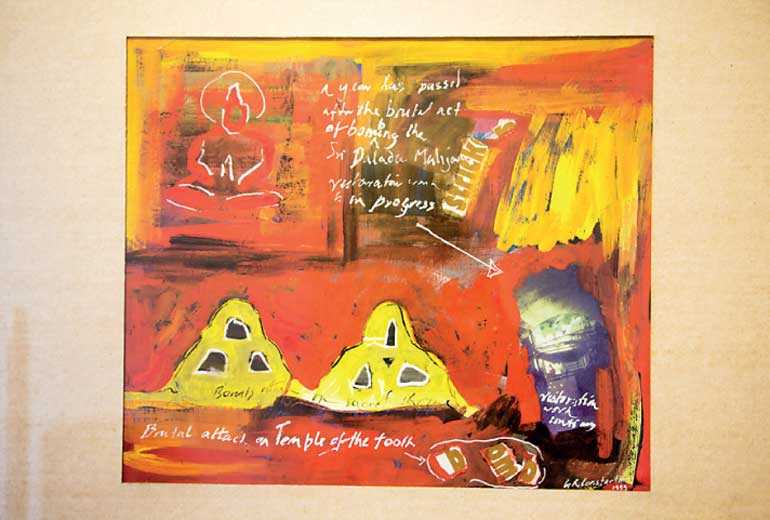

G.R Constantine’s ‘Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic’ (1999) depicts the historical atrocity of the bombing of the Sri Dalada Maligawa in the centre of the hill capital Kandy in 1998 by the LTTE

‘A Vehicle Called Woman’ (2000) by Anoli Perera. She is the most significant female artist of this period. Her preoccupation has not been with political violence and pain but with the experience and politics of being a woman in contemporary Sri Lanka

“What surrounds our understanding or do we only ever know part of the truth? This is for me is true politics – where one never sees the real or whole picture,” says Muhammed Cader in his painting ‘Nightscape’ (2000). His scenic vistas are reminiscent of the way the world might be naturally framed as a reflected image through a puddle of water

Jagath Weerasinghe poses against Sarath Kumarasiri’s ‘No Glory’ (1998). This trouser represents the suburban schoolboy in the ’80s, with a notebook in his pocket. Sarath created this artefact as a memorial for the thousands of youth who lost their lives in the violence of 1980s

When you see Chandraguptha Thenuwara’s famous ‘Barrels’ in a gallery, you wonder what are they doing there. The Barrellism installation (1997) acts as a metamorphosis of roles assigned to an inanimate object while marking the loss of innocence in society at large