Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday, 21 September 2019 00:07 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

1988, Jaffna war widows

On the same day that the President called for the expedition of investigations into the Central Bank bond scam, labelling the continued delays a hindrance in the quest for justice, elsewhere in Colombo there was another long-running quest for justice that was getting considerably less coverage.

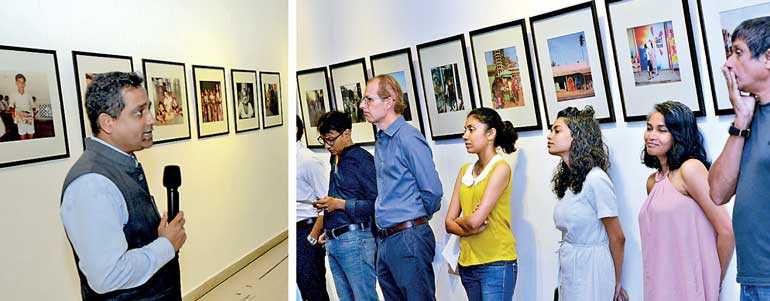

A two-day exhibition was held in commemoration of the 900th consecutive day of protest by mothers and widows of the disappeared in Mullaitivu; the exhibition was also held in line with International Day of the Disappeared on 30 August.

Showing at the exhibition, held from 28-29 August, was the first public screening in Sri Lanka of ‘The Tent’ – there have previously been two solo exhibitions in the UK. The 21 min 15 sec movie is unique in that it’s shown on two simultaneous projections, side by side.

It focuses on some of the wives and mothers of the missing in Mullaitivu, in northern Sri Lanka, where the war came to a brutal end. The women’s protest took place for over a year. The tent faces a Local Government building across the road, the focus of the protest. The women kept a small fire burning in the corner to make tea and food, they swept the outside and insides of the tent, and threw water on the ground to keep the dust down. They also waited. It is on these quieter days there was a palpable sense of loss, when the waiting was punctuated by domestic chores and reflective conversations of the women.

The film contrasts life on these quiet days in the protest camp against footage of large crowds and the visiting media’s demand for drama, on anniversary days of consecutive protest. It is a commentary on the promiscuous gaze of the media, which often focuses on immediate or new events. When ongoing stories are reported on repeated coverage can often desensitise audiences.

The film invites audiences to consider the meaning of loss in light of intermittent media coverage. The Tent becomes a metaphor for the world the protesting women inhabit trapped between hope and grief.

“Tens of thousands of people disappeared during the civil war. The most egregious instance, and I think it was probably the largest single disappearance event, was right at the end of the civil war when several hundred men women and children surrendered to the armed forces and they were never seen again,” explains the movie’s Director Kannan Arunasalam.

“Mothers and wives of those disappeared pursued habeas corpus applications, and I followed them to the courts in Mullaitivu, to face really a callous reception. They were cross-examined to the point, did they know the number plates of the buses that took away their loved ones? Those cases ended unsuccessfully, and during that period I met the women that are protesting in the tent. As a documentary filmmaker you’re looking for a narrative arc with which to tell your story – a beginning, middle and end. For me the women in the tent, their lives were frozen in time, so I wanted a way to capture their waiting, their searching, their not-knowing, in an immersive and emotional way. And so I thought that this film installation was a way of capturing that.

“For me after meeting them what I found more compelling were the quiet days. Where just two or three women held fort, they still marked the days. Their long days of making were punctuated with lots of tea-making, domestic chores, and reflective conversations. And I thankfully managed to convince them to let me film them in that environment, because I ultimately felt that that was something that needed to be captured. And that sense of loss was palpable in that environment.”

In Sri Lanka, the cruel history of enforced disappearance continues to cast a shadow as justice is denied to as many as 100,000 families.

Relatives of the disappeared, many of them women, have spent years searching for truth and justice. Obstructed at every turn, they have been misled about the whereabouts or fate of the disappeared, subjected to threats, smears and intimidation, and suffered the indignity of delayed trials and a stalled truth and justice processes.

Despite international commitments to end impunity for enforced disappearance, the authorities have failed to investigate these cases, identify the whereabouts or fate of the victim, or prosecute those suspected of the crimes.

Since the 1980s, Amnesty International estimates there have been at least 60,000 and as many as 100,000 cases of enforced disappearance in Sri Lanka. The victims include Sinhalese young people who were killed or forcibly disappeared by Government death squads on suspicion of leftist links in 1989 and 1990. They include Tamils suspected of links to the LTTE, disappeared by police, military and paramilitary operatives during the conflict from 1983 to 2009. And they include human rights defenders, aid workers, journalists, Government critics, and prominent community leaders.

The need for greater political will

In June 2016, former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, who was in office from 1994 to 2005, acknowledged receiving at least 65,000 complaints of disappearance. The true figure could be as high as 100,000 people, Amnesty International estimates, as communities who have lived and continue to live under a pall of fear and without confidence in the authorities have not reported other cases.

In 2016, the Sri Lankan Parliament ratified the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. In July 2018, a bill to implement the Convention by criminalising enforced disappearance in the Sri Lankan Penal Code was passed by parliament. Also in 2016, Parliament passed a bill to establish the “Office of Missing Persons”. While a laudable step, the Government failed to consult with victims and civil society or address their concerns about the bill.

Where the Government has reached out to victims, it has ignored what they have to say. Public consultations on the design of justice, truth and reparation mechanisms drew more than 7,000 submissions, including many from families of the disappeared. But officials have shown little interest in the findings and even denigrated the Task Force that organised it.

The Office on Missing Persons (OMP), although legislated in 2016, only became operational in early 2018. To date, the Office has established three regional offices in Matara, Mannar and also in Jaffna just last week. As an observer in the excavation of the second mass grave discovered in Mannar, the Office provided crucial oversight to the carbon dating process and handling of human remains – a process, and the integrity of which has come into question in the past. An Interim Report was released in 2018, however there is little clarity on if and how the Government plans to implement the critical recommendations made therein.

OMP Chairman Saliya Peiris, speaking at the launch of the exhibition, bemoaned a lack of political will in addressing the issue of the disappeared.

“I think we need greater political will. We need greater political will and if we want to help the missing, to help many people find the truth, there are many things in our country which will have to be improved on,” stated Peiris.

“For instance, with the present forensics we don’t have any expert investigators, we have been struggling to recruit people who can do the job of investigating and tracing. But we also need the political establishment, they must understand that there must be more attention on all of this, not just lip service. It’s not worth the budget saying on paper you’re allocating this much to the OMP, unless the ground realities change.”

Peiris also called took aim at the lack of accurate coverage in the media when reporting on disappearances, and explained how that added fuel to a hostile views held by the general public on the matter.

“Unfortunately many people refuse to acknowledge that disappearances have happened in our country. During our interactions with the media, especially among the Sinhalese media, we have had huge articles by journalists from some of the national newspapers, saying ‘why do you say there are disappearances?’

“This is the reality in Sri Lanka where people are denying that disappearances occur, or people are justifying disappearances. If you look at Facebook, social media, if you look at some of the comments. Almost encouraging disappearances. I saw a post saying ‘so and so doesn’t disappear those who are loyal to the country, only those who are disloyal will disappear.’ I think as a society we have to counter this, but this is not easy because there’s such a deep gap between expectations in the north and east and the rest of the country.

“The sad reality is that the many people you portray in your film, many of them will not have the answers before they die. This is the reality of disappearances all over the world.”

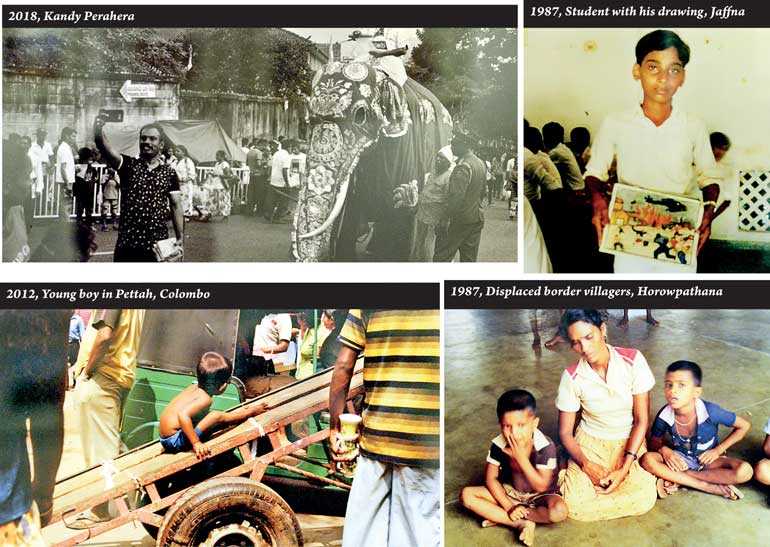

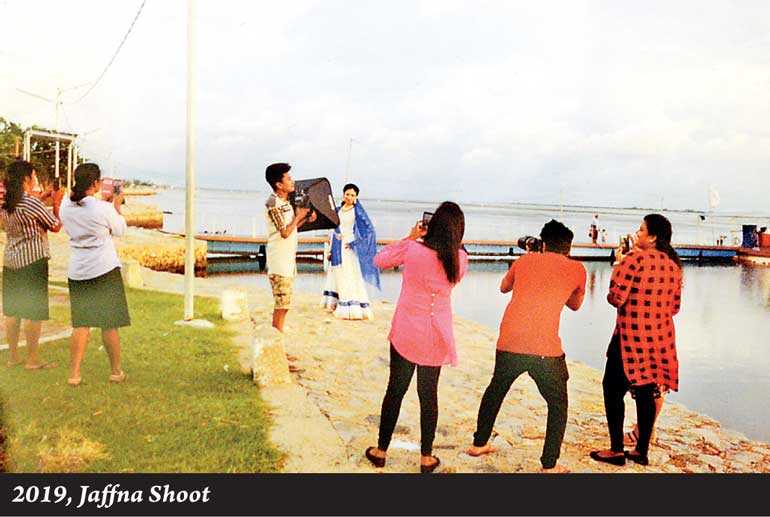

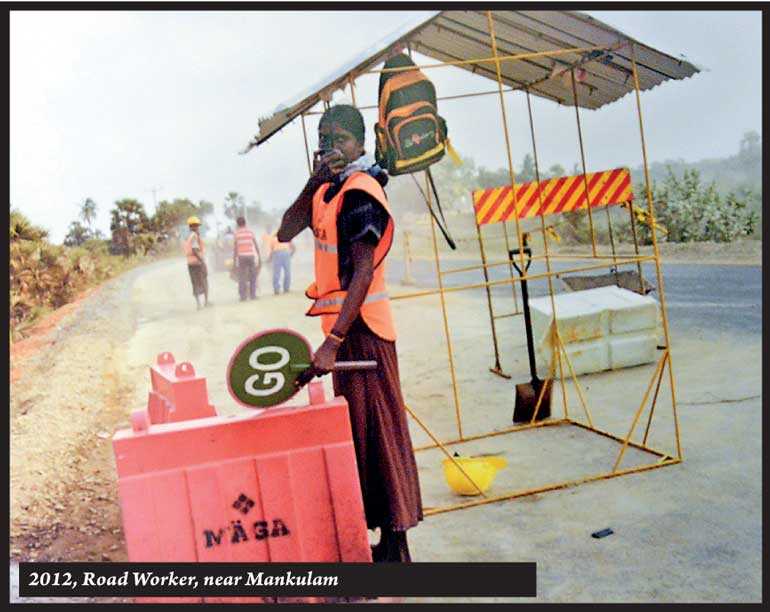

Portraits of a generation

Alongside the film installation of ‘The Tent,’ was a series of photographs. A few months ago Arunasalam invited his friend, photographer Stephen Champion, to join him in exhibitions in Colombo and Jaffna, asking him to select 25 photographs to show alongside ‘The Tent’. This series of photographs is drawn from the photographic negative film and print archive that Champion has created in Sri Lanka during the last 33 years.

“It was a challenging task given that my archive of thousands of photographs is analogue in boxes in the UK and difficult to search. The chosen works mirror the essence of Kannan’s installation and aims to share memories that have affected all parts of Sri Lankan society, whether remembered or not, and to reflect on the current environment with all its many faces and facades and which often veneers the inner worlds of memories and experience,” explains Champion.

“In my experience violence is never acceptable in a world full of bombs and ammunition, it creates further division. There are no winners. Can there be war crimes, when war is the crime?”

Pix by Shehan Gunasekara