Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday, 7 April 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Shivani Vora

New York Times: The story of the fashion scene in Rwanda today is a story of hope.

In a country often defined by its horrific genocide in 1994, when an estimated 800,000 people — mostly Tutsi men, women and children — were killed in 100 days, a new generation of passionate designers wants to create a future where their African nation is known for producing stylish clothes and accessories and not only its dark, traumatising past.

The Government is priming these designers for success through an initiative called Made in Rwanda, aimed at supporting the production of local goods and limiting imports — sending Rwandan designers abroad to participate in trade shows and not taxing them to import fabrics and other materials they need for their designs are two examples of the help Made in Rwanda offers.

On my recent trip to the Rwandan capital of Kigali, a city of verdant hillsides and 1.1 million people, I met Daniel Ndayishimiye, who, in 2016, established Fashion Hub Kigali, a nongovernmental organisation that is also supporting designers.

Fashion Hub helps more than 100 designers in Rwanda by offering them training and access to tools such as pattern cutters and sewing machines. Ndayishimiye’s father and brother were killed in the genocide, but he said that he has every reason to look ahead, not back.

“I have a purpose,” he said. “I want Rwandans to be proud of donning designs by fellow Rwandans.”

Ndayishimiye grew up with aspirations of being a fashion photographer but said that there was no fashion in Rwanda to shoot. “Fashion was non-existent, but today, there are designers all over Kigali, and throughout the country,” he said.

I spent a day with him driving around Kigali so that he could introduce me to some of the Fashion Hub’s designers.

Inkanda House

Inkanda House

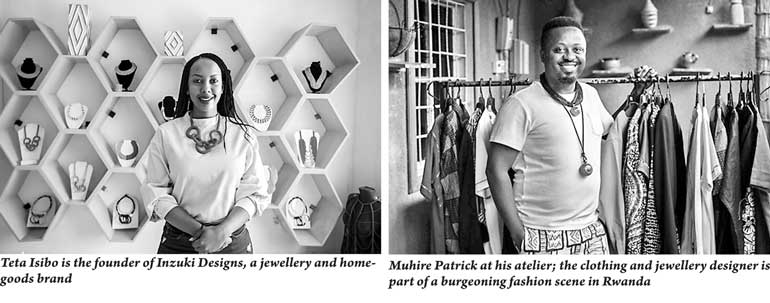

Our first stop was to see clothing and jewellery designer Muhire Patrick at his atelier, in the industrial Gikondo neighbourhood. Patrick’s foray into the business was unplanned when his sister was getting married in 2009, he couldn’t find anything that he wanted to wear for the celebrations. “I went to every possible store in Kigali, and then one day, on a whim, I decided to create the outfits I envisioned,” he said.

Friends and family at the wedding complimented his modern look infused with Rwandan touches such as colourful patterns and asked Patrick if he would make for pieces for them, too. When the inquiries kept pouring in, he launched his label, Inkanda House.

Patrick, along with a small team of women, hand stitch the clothes — a mix of casual and formal — at the atelier, and while visitors are encouraged to peruse the racks hanging with finished pieces, they can also place custom-made orders.

Ki-Pepeo Kids

But adults aren’t the only market Rwandan designers are seeking Ndayishimiye also took me to meet the children’s clothing designer Priscilla Ruzibuka at her store, Ki-Pepeo Kids in Kimironko, a residential area. Ruzibuka launched her label in 2016, a year after graduating from Oklahoma Christian University. She was intent on finding a way to help women affected by the genocide. “These women typically worked as maids, and I wanted to offer them more opportunity,” she said.

Eventually, she decided to make children’s clothes and employ only underprivileged women for the business. Ki-Pepeo Kids currently has four female employees, who help stitch the line’s casual pieces that incorporate typical Rwandan patterns such as animal prints and zebra stripes.

The brand has had a strong start in early 2017, Ruzibuka received a $10,000 grant from the United States Agency for International Development and used part of the money to buy electric sewing machines. Also in 2017, the Rwandan Government, as part of the Made in Rwanda initiative, paid for her to attend the children’s clothing trade show, Children’s Club, in New York. “The show was incredible exposure for me, and since then, I’ve gotten orders for clothes from abroad,” Ruzibuka said.

Rwanda Clothing

Rwanda’s pool of fashion designers who are in their 20s to their 40s extends beyond the Fashion Hub.

Joselyne Umutoniwase, the founder of the fashion brand, Rwanda Clothing, for example, is renowned in the country for her stylish cuts with African-inspired patterns for both genders, which she describes as “modern African.”

When I visited Umutoniwase at her sprawling three-room store in the heart of Kigali, she told me that local residents have recently started to appreciate fashion. “Rwandans like to dress up and are getting into wearing the latest styles,” she said.

This newfound interest is the reason that Umuntoniwase hosts two fashion shows a year for her brand at various locations around Kigali. These “parties,” as she calls them, are a chance for fashion-conscious Rwandans to have a fun night out and socialise with each other.

Kigali Fashion Week and CollectiveRw

Kigali is also home to at least two other fashion events including Kigali Fashion Week, which started off as a small endeavour in 2012, with 10 designers exhibiting their styles but now has more than 30 participants. Two years ago, seven Kigali designers banded together to form CollectiveRw, and regularly host pop-up stores around town as well as an annual fashion show, where the price for a ticket starts at about $18. The collective’s second annual show, in June 2017 at Kigali Exhibition and Conference Village, had more than 800 attendees.

Teta Isibo, the founder of the jewellery and home-goods brand Inzuki Designs, is one of the collective’s members, and said that the group wants to push Rwandan fashion on both a local and international scale. Isibo’s bold and colourful trinkets are already sold at a handful of retailers in the United States including the gift store at the Field Museum, in Chicago, but she dreams of a bigger presence all over the world.

“I’m part of a lucky generation of young Rwandans who have the opportunity to create our own reality and not feel held back because of the genocide,” she said. “I see a future for us that’s bright, and one where fashion thrives.”

Pix by Jacques Nkinzingabo for The New York Times