Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Saturday, 5 January 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

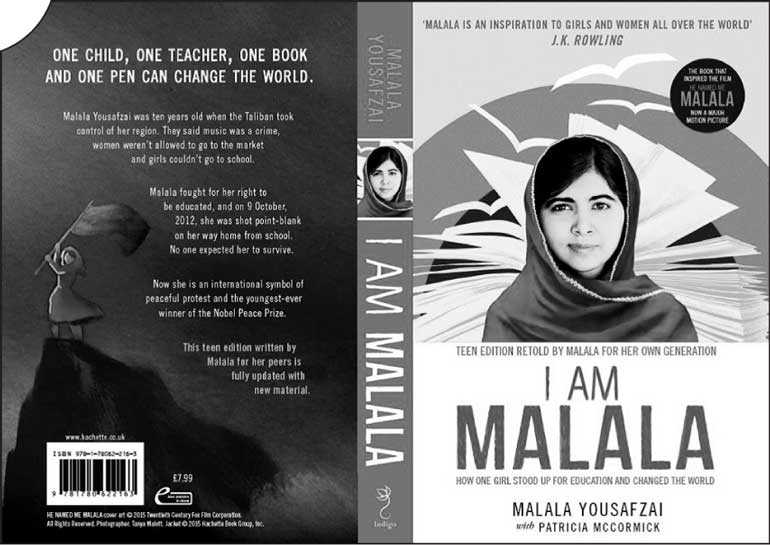

During Malala’s recent visit to Australia, among the many merchandise items for sale were the latest edition of her biography and the book on her father’s life story written by him. She has updated her biography from the first edition in 2013.

During Malala’s recent visit to Australia, among the many merchandise items for sale were the latest edition of her biography and the book on her father’s life story written by him. She has updated her biography from the first edition in 2013.

The new edition, in fact, is the ‘Teen edition retold by Malala for her own generation’ and the author is different from the one who did the earlier book. Another book on her story meant for kids with lot of drawings has also been released.

In ‘I am Malala’ introducing herself as “a girl like any other – although I do have my special talents”, she says she is double-jointed and is able to crack the knuckles on her fingers and toes at will. “I can beat someone twice my age at arm wrestling,” she claims. She then goes on to discuss her long adventurous journey written in the most interesting fashion.

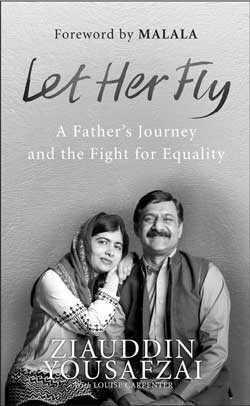

Since Malala’s story is well known let’s take a glimpse of the father’s story related in ‘Let her fly’.

Malala’s father, Ziauddin Yousafzai has been a school principal, a social activist, an active social worker. Describing him as her idol, Malala introduces him as “the personification of love, compassion and humility for as long as I have known him”.

‘Let Her Fly’ discusses his journey from a boy in a small village in the mountains of Pakistan to becoming an activist for quality across the globe.

Accompanying Malala on her first visit to Oxford University where she gained admission to Lady Margaret Hall, Malala’s father recalls how they were taken on a tour by two students. At the end of the tour the principal of the College led them into a large drawing room where small clusters of people had gathered around chairs and sofas chatting in low voices.

“Across the room, I saw the principal make his way over to the tea-making machine. The principal picked up a cup, dropped in a tea bag from a nearby container, and placed the cup under the machine, filling the cup with hot water. After a few seconds, he placed the cup on a saucer and poured some milk. After stirring the cup and throwing out the tea bag, he picked up the cup and saucer and crossed the room with this one cup of tea. There were lots of us who did not have a cup to hold, but he continued until he reached his destination and at that point, he handed the cup to Malala. I started to cry.”

Coming from Pakistan where the males never made a cup of tea and it was essentially a task for women he could not believe it happening in any other country. So when people ask him what his proudest moment in life is, and they expect him to say ‘Malala receiving the Nobel Peace Prize’ or ‘when she spoke to the UN’ or ‘when she met the queen,’ his answer is: “It was when the male principal of Lady Margaret Hall made and served Malala a cup of tea.”

Coming from Pakistan where the males never made a cup of tea and it was essentially a task for women he could not believe it happening in any other country. So when people ask him what his proudest moment in life is, and they expect him to say ‘Malala receiving the Nobel Peace Prize’ or ‘when she spoke to the UN’ or ‘when she met the queen,’ his answer is: “It was when the male principal of Lady Margaret Hall made and served Malala a cup of tea.”

Why does he say so? “It was a moment so natural, so normal, and therefore more beautiful and powerful for me that any audience Malala might have had with a king, a queen or a president,” he writes.

For him the principal’s act “symbolised the end of a fight I had waged for two decades to ensure equality for Malala”. He continues: “Malala is an adult now, old enough and experienced enough to fight her own fight. But the fight for all girls. All girls, all women, deserve the respect men have automatically. All girls should be offered a cup of tea in their learned institution – be it in Pakistan, in Nigeria, in India, in America, in the UK – both for its own sake, and for all that it symbolises.”