Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 24 November 2018 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Poachers get paid just $ 200 to kill a rhino and extract its horn, but rhino horns can go for anything from $ 50,000 to $ 300,000 in the Asian market, reveals Ravi Perera

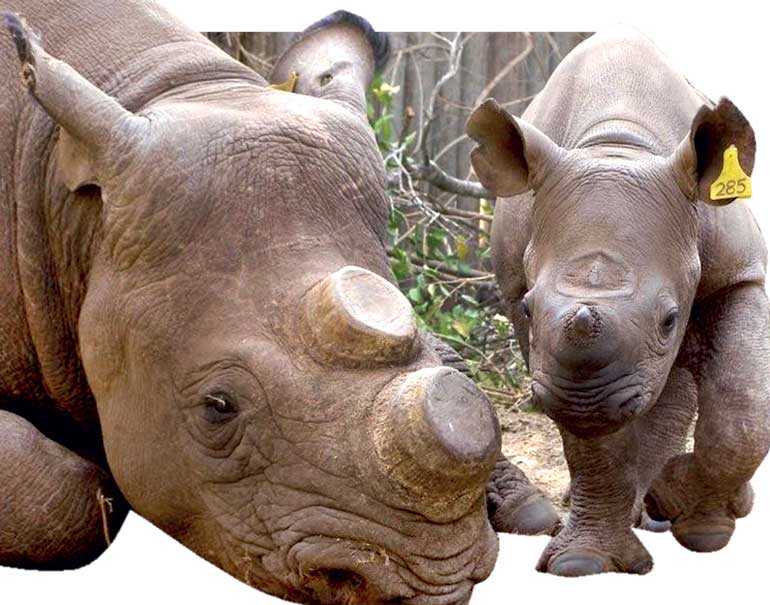

There are currently only 3,900 tigers and 30,000 rhinos left in the wild. The animals are threatened by poaching and habitat loss

By Madushka Balasuriya

Sri Lanka as a wildlife destination has for quite some time now been somewhat of a hidden gem; those who know ‘know’, but for the most part it has stayed clear of true global awareness. This however is unlikely to be the case for much longer, especially as travel website Lonely Planet recently saw fit to rank our humble island nation its number one travel destination for 2019.

While such publicity undoubtedly has widespread ramifications right across the country’s travel and tourism sectors, it should put those attached to the country’s wildlife conservation departments on particularly high alert. Because with such exposure comes a whole new audience, and a whole new array of problems – namely, poachers.

To date however, the country has, thankfully, not had to deal with the scourge that is the global animal poaching industry. But look across at other wildlife hubs such as those in Africa, and you can see its devastating effects.

According to the latest figures, poachers kill an elephant every 15 minutes, while every 19 hours a rhino is slain – for the sole purpose of extracting their horns and tusks. For Sri Lanka, a country which Lonely Planet describes as having “oodles of elephants,” these sort of statistics can set off alarm bells. Though, admittedly, these concerns are tempered by the fact that only male elephants in the country boast the tusks which poachers covet, and of the male population only 5-6% are tuskers.

Such a small percentage is probably one of the main reasons as to why poachers have yet to set their crosshairs on Sri Lanka’s tuskers, though the size of the illegal wildlife trade globally means one can never be too cautious.

“Poachers get paid just $ 200 to kill a rhino and extract its horn, but rhino horns can go for anything from $ 50,000 to $ 300,000 in the Asian market,” reveals Ravi Perera.

Perera is a Crime Scene Investigator who has worked with the US Federal Government for the last 25 years, a period of time in which he has served on various task forces targeting crimes such as weapons trafficking for cartels, gun trafficking from the USA to Mexico, and money laundering, among others.

How to catch a poacher

He was in Sri Lanka recently to share his experiences as part of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society’s (WNPS) monthly lecture series, in a lecture titled ‘CSI: Wildlife’. In a presentation that contained several bits of classified information, Perera revealed how he has been incorporating his work as a CSI into wildlife conservation.

“I run a safari company in Kenya, and I was at a wildlife park where I was talking to the anti-poaching units. I was talking to them from the law enforcement side, and they were telling me that they catch so many poachers, but there is no evidence or prosecution, so someone comes and releases them,” he explained.

“The case gets thrown away if there’s nothing to support the case. To prosecute somebody you need evidence.”

Having graduated from the FBI Forensic Academy in Quantico, Virginia, Perera specialises in shooting reconstruction and surveillance photography, while he is also certified in electronic forensics, where analysis of cell phones and computers produce significant evidence of criminal activity.

“Now anti-poaching units are using gunshot detectors to see what direction gunshots are coming from. But still there are a lot of semi-automatic AK-47s in use – sometimes you get situations with about 50 poachers with these guns just wiping out a herd of elephants. They then just get the tusks and they’re gone before the anti-poaching units can catch them. And a lot of guns, the poachers will just shoot the animals and then dump the gun in the bushes.

“You can hear it, it’s like New Year’s Eve night – they’re just shooting elephants out there. You can see the bodies of dead elephants from the air if you fly over certain areas in Africa.”

To catch these monsters, Ravi, who is also the CEO of Serendipity Wildlife Foundation, has trained Anti-Poaching Units in Kenya, and also introduced Gun Shot Residue (GSR) testing, which helps to identify the shooter when many people are present at a crime scene, through the use of disposed guns in the wild.

“GSR is absolutely crucial in Kenya because, usually, the game guards catch a group of poachers, but can only prosecute the person who fired the particular gun that was fired.

“Whenever a gun is fired, whoever fires it, there is residue that comes out of the gun and it’s on that person’s hands or clothing. So in the US we use this to identify the shooter. There can be 10 suspects out there, and we’ll just test everybody’s hands and finally find the person responsible for firing the gun.”

Last year a project was started by Ravi to detect fingerprints from elephant tusks and rhino horn, which would help identify individuals involved not only in poaching, but in trafficking as well. The second phase of the project is to start a fingerprint database dedicated only to wildlife crimes.

“My organisation is going to be building up a fingerprint database just for wildlife crimes. Interpol already does that but it’s mixed with other criminal activities, we want to do one exclusively for crimes related to wildlife. And eventually we want to do that in Sri Lanka as well, if the opportunity arises.”

The use of science has been gaining traction as of late, especially with news earlier this year that DNA from different shipments of elephant tusks had been used to connect the shipments to the same global ivory trafficking cartels. Science Advances reported that this technique has already revealed the presence of three major interconnected cartels presently active in Africa. For Ravi, this is a crucial breakthrough in catching ever more elusive smugglers.

“It is amazing the kinds of criminal acts that take place all for the love of exporting these horns and tusks to different parts of the world. And don’t just think that Asia is the only place where this stuff goes to. The other two primary countries, next to Asia, which are the largest importers of ivory, are the US and England.

“And they’re very smart; they don’t take a direct route to China. They’re careful in what they do because they’re dealing in billions of dollars. I’m pretty sure we’re not even catching 50% of the ivory that is being traded out there at the moment.”

Obstacles

Despite these advances in anti-poaching measures, there are still considerable obstacles preventing their effective implementation, the most common being political interference and corruption, explains Ravi.

“We cannot trust the game guard sometimes because the game guard is paid more by the trafficker or the poacher. There is a lot of foreign involvement.

“To go off-road you need a permit, but the game warden who handles that doesn’t give you a receipt and puts the money in his pocket. They had to switch the payment method at the entrance to all the game parks to credit card, and buying the ticket online, because people were running away with the money.

“The dollar goes a long way there when the average person is paid $ 125-150 a month.”

There is also the issue of bringing in employees from abroad to train or, at times, replace the local staff.

“You need the right personnel to do what you want them to do. You need to trust them. You need to make sure they’re qualified.

“You bring someone in, the current worker questions you, asking you why you’re bringing someone in from outside when they feel like they could do the same job. Well maybe there’s a reason we need people from outside, because you’re not doing a proper job.”

What of Sri Lanka?

While several of these issues and problems do not relate to Sri Lanka as of yet, a recent change in the Flora and Fauna Protection Ordinance (FFPO) has got several wildlife conservationists concerned.

The Government recently proposed the lifting of a ban on transporting and selling wild boar meat so as to offer farmers an additional source of income. Environmentalists warn however, that this could lead to the commercialisation of hunting.

“The problem is that it may not be just wild boar meat that is being transported. It could also be so many other animals, although we’re being told they are just wild boar,” explains WNPS Vice President Ranil Peiris.

“It might actually open the floodgates, so we’re going to have an interesting time coming up in the future.”

Peiris added that, along with that, one of the other key challenges the Wildlife Department in Sri Lanka has on the few occasions they catch poachers is in being able to prove their case. He hopes that a future venture with Ravi will help aid in that cause.

“The WNPS would probably like to work in the future with Ravi and the Wildlife Department and try to find a way of actually apprehending these poachers. With evidence only they can be prosecuted, and these crimes can be stalled or stopped sometime into the future.”