Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 12 January 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

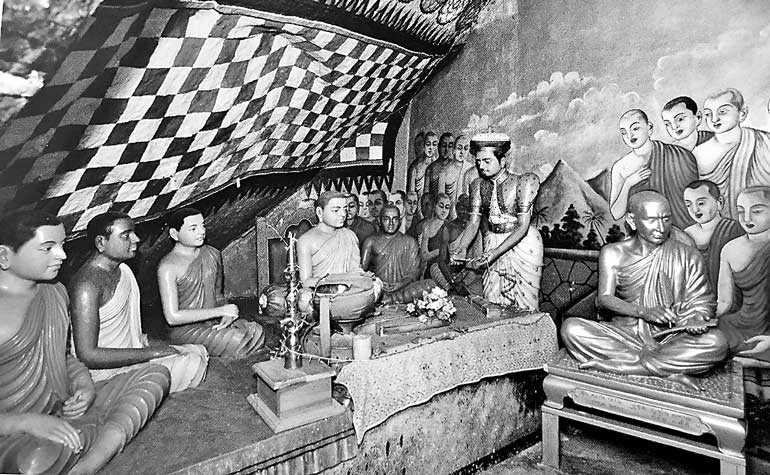

The writing of the Tripitaka as depicted in images at the Aluvihara temple

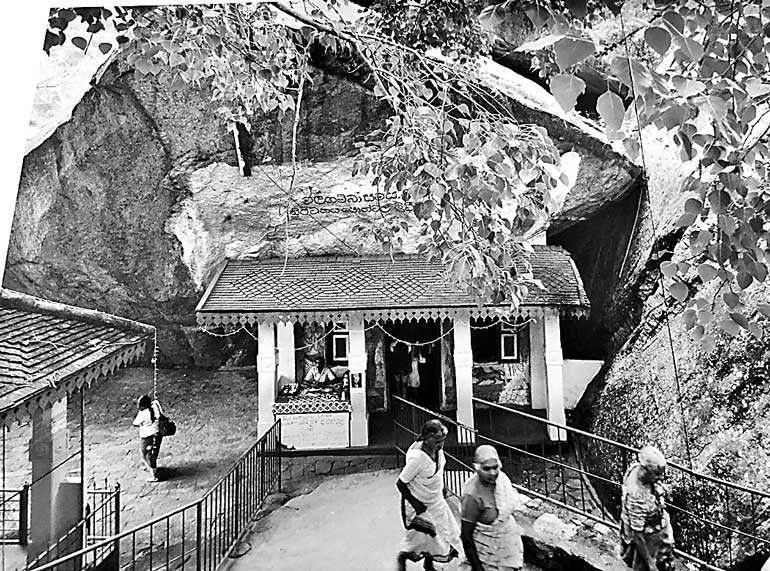

Aluvihara cave temple

“The greatest contribution that the Sinhalese people had made to the intellectual heritage of mankind,” is how Professor Senarat Paranavitana, renowned archaeologist, describes the writing of the Buddhist Canon (Tripitaka). Until the Tripitaka was written, the monks memorised the contents, thus maintaining an oral tradition.

“The greatest contribution that the Sinhalese people had made to the intellectual heritage of mankind,” is how Professor Senarat Paranavitana, renowned archaeologist, describes the writing of the Buddhist Canon (Tripitaka). Until the Tripitaka was written, the monks memorised the contents, thus maintaining an oral tradition.

After several centuries the Tripitaka was declared as a National Heritage by the President a few days back. The ceremony took place at Aluvihara cave temple where the monks wrote the Tripitaka.

|

Writing with the ‘panhinda’ |

Scholar monk Venerable Walpola Rahula explains why the Tripitaka was written down, in his book, ‘History of Buddhism in Ceylon’: “During the latter part of the 1st century BC the whole country was violently disturbed by a foreign invasion on one side; on the other it was ravaged by an unprecedented famine. The whole island was in chaos. Even the continuation of the oral tradition of the Tripitaka was gravely threatened. The far-seeing Maha Theras decided as a last resort to commit the Tripitaka to writing at Alu-vihara, so that the teaching of the Buddha might prevail.”

The historic event of writing the entire Buddhist Canon (Tripitaka) and the Commentaries (Atthakatha) took place during the reign of King Vattagamini Abhaya (29-17 BC). Five hundred monks led by Venerable Rakkhita undertook the task of writing the Tripitaka. They inscribed the words in the Pali language on ola (talipot palm) leaves. This was the traditional art of writing where the ola leaves are first dried and seasoned. The seasoning of the leaves is a delicate operation.

The leaves for writing are obtained from an opened leaf bud which is carefully cut and brought down ensuring that the leaves are not bruised. The buds measure between 10 to 20 feet in length and contain about 80 to 100 leaflets.

Once the leaf segments are separated, the mid-rib is removed, thereby gaining two strips from each. These are rolled and dipped in water in a copper cauldron and boiled gradually with raw papain, the milky secretion of the papaya, unripe papaya pulp and pineapple leaves. Papain softens the talipot leaf fibre, making it flexible.

After three to four hours, the leaf rolls are unfurled and hung up to dry. They are sun-dried for three days and left outside for three nights to catch the dew. The golden coloured leaves are then stored in the kitchen attic in rolls. The wood smoke from the hearth adds to their durability.

When needed for writing the leaf is unrolled from both sides and polished to get a satin finish by pulling the strips back and forth on a smooth cylinder of areca nut.

A ‘panhinda’ (stylus) turned out of gold, silver, copper or brass is used as the writing instrument. Their handles are most often elaborately carved using traditional motifs and designs. The writing is incised on the leaf with a steel point.

Writing on ola leaves continues to this day mainly in temples where the monks use the technique to document vital information which needs to be preserved for posterity. The ‘pirith potha’ – the book of protective stanzas – in every temple has been recorded on ola leaves and is used by monks when reciting ‘pirith’, particularly during an all-night chanting.

While writing a book (‘The Great Revival’) for the Buddhist Publication Society to commemorate the 250th anniversary of ‘Upasampada’ (higher ordination), we spent time at the Malwatta Viharaya in Kandy with Ven. Kulugammana Dhammarakkhita Thera, head of Sri Sangharaja Pirivena who guided us, arranged for photographs to be taken of the preparation and writing on ola leaves. He is featured in the pictures taken by Sarath Perera.

Polishing an ola leaf