Tuesday Feb 03, 2026

Tuesday Feb 03, 2026

Saturday, 19 September 2020 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Sasanka Nanayakkara

By Sasanka Nanayakkara

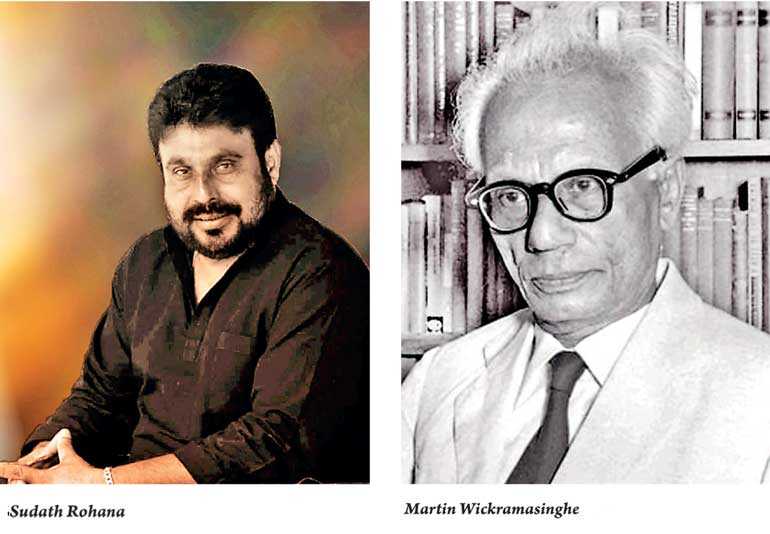

How many of you have had a tear in your eye after watching Sudath Rohana’s ‘Karuwala Gedera’ adopted from the 1960 novel of Martin Wickramasinghe? I am sure many a sensitive mind would have induced a timely release.

What is this gloomy undertone in Wickramasinghe’s letters that kindle a melancholic flicker in your heart time and again? Is it a trace of deep Buddhism that talks of impermanence which he may have mastered before he fashioned his fingers to write?

The story is centred on a small family that lived in the southern village of Koggala from about 1920 to 1945 and unfolds events of their journey of life.

Torturous account of guilt

When a phenomenally successful Sirimal, now a matured advocate, decides to visit his former village in Koggala after the World War was over, the reader is made to await a tour of a once-familiar landscape described so vividly at the beginning to roll by. But what does the reader get instead? A torturous account of turbid feelings of guilt he is tormented with.

He had virtually abandoned the village upon reaching the commercial and matrimonial heights in Colombo and his visit is made to look as if to seek some solace from those memories haunting him in later years. Alas! There is nothing much left of the village to reminiscence anymore, he finds out in the film adaptation.

The villagers have been forced to vacate Koggala after their lands acquired by the ruling British to build the airport runway for the use of aircraft and even the Brits have left their temporary detachment, leaving not a vestige of Sirimal’s former childhood haunts. Through a repenting pair of Sirimal’s flustered eyes Wickramasinghe makes the shocked reader poignantly meander through a maze of rubble; all that is left of their former habitat now swallowed by rank shrub.

Reading between the lines, it is not difficult to assess the protagonist’s inner struggle to come to terms with reality. He mechanically stops at the side-turned old sekkuwa on which a banyan parasite is now seen flourishing, concealing half of it with its tangle of roots.

His father who was clad in a loin cloth and wearing a checked turban used to sit on a funny seat installed on a long wooden shaft projecting out at an elevation which was connected to the stone-grinder in the centre. He was driving a bull tied to the shaft at some speed and his loku amma (Rathu Hamine) used to feed the grinder with more copra when the oil extract had filled the container from the outlet at the bottom.

His own amma (Podi Hamine) who wasn’t a patch on loku amma when it came to spirited physical support watched the proceedings from the doorstep. The desolation brought about by a gust of nostalgia seizes Sirimal. He leans on to a dead coconut trunk in a daze.

Sirimal’s languorous attitude

The book however has made the reader to take in more liberally Sirimal’s languorous attitude toward the village, and whilst feeling guilty of abandoning his next of kin, he doesn’t seem to mind the obliteration of the village.

He eyes the new wide roads and orderly culverts with some enthusiasm; neatly completed and tarred by the British like in the city, and even contemplates of investing in a land overlooking the lake should such become available for a song. His final thoughts give rise to how he despises his old village and its shallowness.

In the film production, Sirimal’s searching eyes now find the ruined shell of the house his father built, which wouldn’t have been a possibility had it not been for his loku amma’s business acumen. It was she who made his father a rich man in the village standards, recalls Sirimal with sadness. But was Sirimal fair by her who was so fond of him when he was a toddler? Though she couldn’t bear a child, wasn’t she a second mother to him until circumstances made her leave the village before Sirimal had hardly left school?

Not enough room for two women

There was not enough room for two women in that house, which was established by Wickramasinghe with such artistry. Though the first one was the legal wife, she was found to be barren and the second was brought in amicably with the approval of the former. Their husband was a hard-working successful businessman then. The elder one; wiry and manly, flat-chested but shrewd and calculating contrasts so well with the pretty, comely, and heavy bosomed much younger one.

The younger one wins many admirers as well who frequent the household ostensibly to do business with her elderly husband but in reality, to seek her adorable company whilst she ceaselessly embroiders renda with her beeralu unit in the open veranda. Here, Wickramasinghe is careful about whom she entertains. It’s not the riff raff but the respected stock in the village in no less than Tissa Kaisaruwatte and Navin of Gam Peraliya fame which runs concurrently to this tale. They are the well-bred clan of the neighbourhood and mean no harm. But such visits make the elder woman jealous and envious. Then the children are born!

At this point the clever author makes the reader comprehend of Rathu Hamine’s economy and her own savings which encourages her decision to accept defeat and leave when all her revengeful attempts to stamp authority in the household fail. Her fated choice as the legal wife yet with no role to play over the custody of the beautiful children followed by the narrative of her forced departure moves the reader to tears. The utter desperation leads to a case of food poisoning as well and how Wickramasinghe builds his narration to a point of no return is remarkable.

In the book, the way the author hides loku amma’s (Rathu Hamine’s) existence thereafter is but sheer craft. The avid reader’s mind longs for some news about her whereabouts but Wickramasinghe makes her disappear from the script without a trace.

However, to the viewer in the film version, the noble gesture of writing loku amma’s legal wife’s share of Sirimal’s father’s house and the compound (invented script by Tissa Abeysekera I presume) in Sirimal’s name much later becomes a praiseworthy act. It’s the plot the film director has used not to let Rathu Hamine’s character slip away in the remainder. But, by doing that the scriptwriter had killed the suspense the clever author had masterfully instilled in the reader’s mind.

A bouquet of roses is on the way for the commendable effort by the talented Director Sudath Rohana in reproducing the epic yesteryear novella which had left a lasting memory with the Sri Lankan reading community. The venture would immensely benefit the future generations who are bound to come across the literal genius Martin Wickramasinghe as an essential study in their curriculum

Twist to the tale

On the other hand, the plot had branded Sirimal as an opportunist, something which Wickramasinghe had been reluctant to do. The twist is more realistic in the book when the boy borrows offering his mother’s own six acres of coconut elsewhere as collateral, of course with her consent. Wickramasinghe makes the dire requirement of capital a must for the boy by inflating the narration on his challenging life in the city so that the reader is made to sympathies with his plight. By the introduced plot, the film director had cast a doubt on Sirimal’s sincerity and instead has made him somewhat a conniving schemer.

It was the time Sirimal was struggling to manage his affairs in Colombo as a law student and he desperately needed some capital to commence his career as an eminent lawyer’s assistant. He also courts the lawyer’s pretty daughter and the film viewer is made to realise the frantic need in Sirimal to impress her affluent Colombo elite parents not only with his attire, his conduct, and his stratum in the high society but with possession of some form of lodging as his own as well.His loku amma’s good deed behind the others’ back makes the rest of the family bewildered but it helps Sirimal to reach his ruthless objective when he covertly meets the rich lender from the village with the deed in hand.

At this stage of the story there are times when the viewer is made to feel sorry for Sirimal’s inadequacies to brush shoulders with the elite which doesn’t differ much from the book. But then, it is before his true self begins to unfold in the film adaptation. There are touching moments as well in the film when his loku amma – now an ageing wasted woman living a lonely life in a distant village – looks at the dashing young man in awe as if he is all she sees as future. Little that she knows she has seen the last of him!

The book speaks nothing of that but how determined Sirimal is to go for his goals and how ambitiously he sets about it. Wickramasinghe also attributes worldly knowledge of languages and literature to Sirimal in addition to the law he is supposed to master which makes him a brilliant prodigy for a boy from a rural village. As such, the author leaves fair amount of room in the reader’ mind to appreciate his efforts. In that wake, the reader seems to not mind him asking his own mother for the deed when the need arises to borrow.

Sirimal’s brother Nimal, who is a village hoodlum turned local politician, somehow finds the money to secure the family silver before the sharp lender eyes to own half of the prime property and the prospering copra business thriving on it. That’s the film production.

Instead, the book finds Sirimal cringing in guilt before the brother (mother holds the news about the pledged land from the brother very diplomatically till the last minute) when the latter questions him politely on the unsettled transaction, now causing some distress to the ageing mother at home. It is then that Sirimal who is utterly stressed-out due to work exigencies, remembers it and he makes swift arrangements to settle with the lender and clear the title in no time. Here again, the author doesn’t let his subject down that easily.

By removing loku amma from the script, the clever author lets a seed of curiosity grow in the reader’s mind to dwell on her wellbeing. After all, won’t the reader look forward for a favour returned to loku amma by an established Sirimal, at least by checking on her whereabouts? But Wickramasinghe shies from that obligation and allows the reader to imagine her cheerless predicament. The spin leaves room for the reader to get more depressed. Thus, Rathu Hamine’s character becomes conspicuous by its very absence in the book, proving the author’s masterly story-telling technique.

When it comes to Sirimal’s parents vacating the village with the rest, the author once again deliberates being vague. At no point does he mention Sirimal being aware of their movement to Kamburupitiya, having made to evacuate. He is kept away from the readers mind for a while which is proof enough for his aloofness from the rest of the family.

On the contrary, before all this, both the author and the film director go all out to prove how estranged Sirimal is from the family by portraying his absence from Nimal’s grand wedding ceremony in the village. At the time Sirimal was married but his family was not aware of it since he had not visited the village for a few years. It is made to understand that his rich Colombo wife is side-lined by her own family over the unsuitable marriage.

Wickramasinghe also makes it a point to paste radical attributes to her though she is born with a silver spoon in her mouth; another attempt to pair the two well in their own comfortable nest. Thus, birth of a cultured urban middle class who don’t belong to the village anymore!

Trademark undertone of sarcasm

Throughout the last chapter Wickramasinghe doesn’t forget to unleash his trademark undertone filled with sarcasm underneath his narration at the existing class differences in the Sri Lankan society, which his loyal followers are pretty much used to reading the more famous trilogy of novels.

Rohana’s film adaptation however seems to have overplayed this aspect, going to extremes (Sheila’s ostentatious grand mansion which could easily be the colonial Governor’s), hence the sweet subtlety the author brings about with intellectual and at times humorous dialogue between Sirimal and Sheila with their close companions in the city, is absent in the film production by some stretch.

In the climax, the clever author hides what causes to stir Sirimal’s precarious mind that much to make him stop by at his former village he detests so much, but makes the reader judge the reason by just an insignificant brushstroke of a sentence about him visiting his next of kin now living elsewhere. The film adaptation slightly fails in picking the right property and surroundings of the 1940s Kamburupitiya which could have been achieved by a single frame of a family luncheon indoors of a period house in Matara.

The vacuum of impermanence leaves the sensitive reader of the book as well as the keen viewer of the film in a deflated state for quite a while to come.

A commendable effort

The film adaptation is reasonably good with remarkable acting prowess of the cleverly handpicked cast, but the direction is not without its shortcomings. Period reproductions are always delicate affairs and I am surprised as to why the director didn’t weaken the colour by several tones like they do in the West with such dated. It would have attenuated the overall brightness of the present and made the viewer more attuned to the laid-back mellowness of the era with more conviction and less doubt.

There were issues with the make-up artist too when ageing maturity needed to be cast. Another noticeable deficiency was the garish colours used on the wooden frames of Thinan Mudalali’s new house he built in the 1920s which was quite unrealistic. Wickramasinghe mentions the ornate mentality of the new rich in the village but colours hadn’t been so shrill (no more than distemper paint then) and the furniture not so crude (not applicable in this case) yet in the 20s. He talks of some such houses in the village but not the one this simple, humble fellow builds.

The house was named ‘Karuwala Gedera’ because of large hovering trees that shaded it. Wickramsinghe often mentions of the giant breadfruit tree in front that was branching out prodigiously under which most of the activities of the household including extracting of oil took place. I wish the production crew found an identical location described so clearly by the author so that the visual could have lived up to what is already drawn in the reader’s mind as imagery. After all, there are enough and more such properties built in the ’20s and ’30s still in existence in the coastal south!

Nonetheless, a bouquet of roses is on the way for the commendable effort by the talented Director Sudath Rohana in reproducing the epic yesteryear novella which had left a lasting memory with the Sri Lankan reading community. The venture would immensely benefit the future generations who are bound to come across the literal genius Martin Wickramasinghe as an essential study in their curriculum.

(The writer can be reached via [email protected])