Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 21 April 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Recently it was reported that Gemunu, the ‘infamous’ bull elephant in the Yala National Park of Sri Lanka, had lost one of his tusks in an altercation with another bull elephant. In this paper Srilal Miththapala, elephant and wildlife enthusiast, explores the behavioral antics of male elephant behavior and the prevalence of tusks in elephants. He also discusses the rare phenomena of serious altercations between male elephants, sometimes leading to injuries and broken tusks

By Srilal Miththapala Male elephants and musth

Male elephants are solitary by nature, having been driven away from the rest of the herd when they reach puberty. This is called ‘natal dispersal’, and is a mechanism that has evolved over the millennia to avoid (a) inbreeding with relatives and (b) competition with kin. After that they lead a nomadic life, sometimes associating with other senior bull elephants ‘to learn the ropes’ of survival and eventually being ready to claim their own female for reproduction.

One reaching full maturity bull elephants, especially the Asian species, come into state called “musth”, in which their urge to mate goes into overdrive and they become very aggressive.

During musth, males are flooded with up to 10 times as much testosterone as usual. They have swollen temporal glands: swellings bigger than a grapefruit that stick out behind their eyes. They are also extremely aggressive, and discharge an almost continuous dribble of urine that creates a scent trail as they walk. The famous elephant researcher Cynthia Moss calls it “a kind of Jekyll and Hyde transformation”.

She goes on to say: “Musth is a form of honest advertising of a male’s sexual availability and condition. To females, a musth bull is saying, ‘I’m in very good condition, I’ve lived long enough, and I can give you a healthy calf that’s going to inherit my good genes, virility, and longevity.’ To other bulls, musth is advertising, ‘I’m in very good shape. I’m surging with aggressive hormones, and I’ll kill you if you challenge me.’ Testosterone-charged musth males sometimes fight to the death.”

Male elephants

and tusks

In the Asian species of elephants (elephas maximus) only the male have tusks while in the African species (loxodonta) both the male and female have tusks. In the case of the Sri Lankan sub species (elephas maximus maximus) only a very few males have tusks which is estimated to be only 6%-7% of the wild elephant population (Jayewardene, J.-1994). However according to the elephant census conducted in 2011 by the Wildlife Conservation Department of Sri Lanka, only 2% of the total population are tuskers.

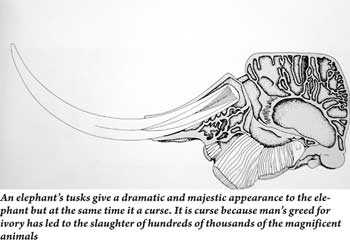

Tusks are really somewhat modified upper jaw incisors of the elephant. The dentine in the tusk is known as ivory and its cross-section consists of crisscrossing line patterns, known as “engine turning,” which create diamond-shaped areas. Much of the tusk can be seen outside; the rest is in a socket in the skull. At least one-third of the tusk contains the pulp and some have nerves stretching to the tip. Like humans, who are typically right- or left-handed, elephants are usually right- or left-tusked. The dominant tusk, called the master tusk, is generally more worn down, as it is shorter with a rounder tip. Tusks continue to grow right through an elephant’s lifetime.

Tusks serve multiple purposes. They are used for digging for water, salt, and roots; debarking or marking trees; and for moving trees and branches when clearing a path. When fighting, they are used to attack and defend, and to protect the trunk.

An elephant’s tusks give a dramatic and majestic appearance to the elephant but at the same time it a curse. It is curse because man’s greed for ivory has led to the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of the magnificent animals.

Iconic tuskers of

Sri Lanka

Possibly due to the fact that only few Sri Lankan male elephants have tusks, sighting a tusker in the wild is a very exciting, and much sought-after experience. Consequently several individuals in some of the wild life parks have become popular icons.

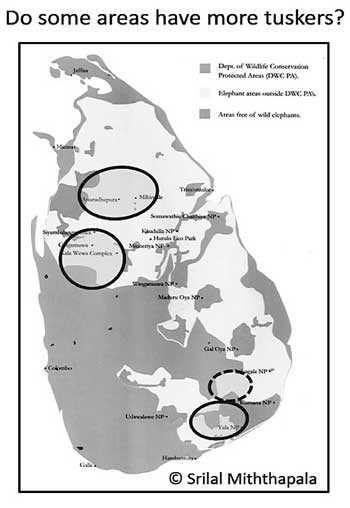

Some of the parks seem to have a higher incidence of tuskers than others. The reasons for this is still not clear but it could be that there is a healthy tusker gene pool in some areas. Kala-Wewe and Yala National Parks definitely have a larger prevalence of tuskers, while the more wild elephant abundant Uda Walawe National park has only a very few.

The infamous Gemunu of Yala Fame

The infamous Gemunu of Yala Fame

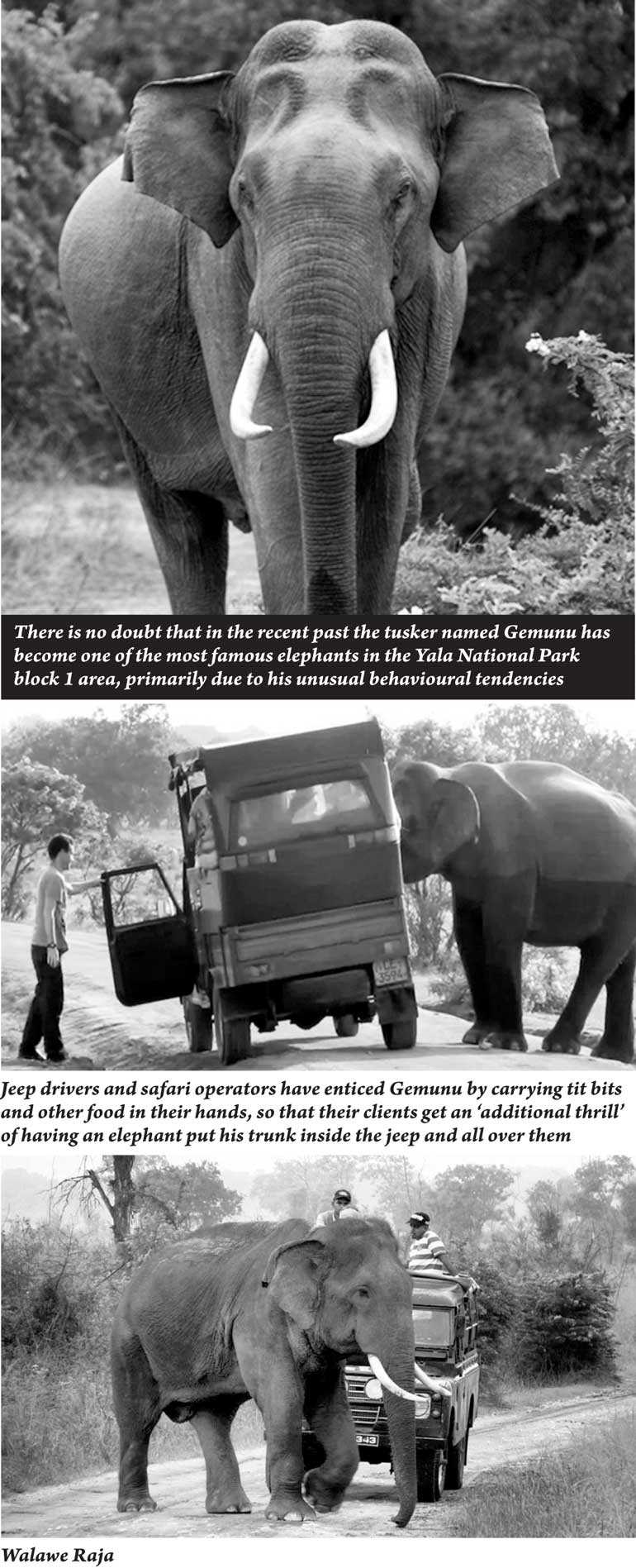

There is no doubt that in the recent past the tusker named ‘Gemunu’ has become one of the most famous elephants in the Yala National Park block 1 area, primarily due to his unusual behavioural tendencies.

He is a young tusker in his prime, possibly about 25+ years old, who frequents Block 1 of the Yala National Park. Gemunu’s notoriety is due to the fact that he has got acclimatised to waylaying jeeps and searching for food in the visitors’ possessions. This has apparently originated (according to unconfirmed reports) of him being fed during his young days at the Sithulpahuwa temple premises.

Subsequently jeep drivers and safari operators have enticed him by carrying tit bits and other food in their hands, so that their clients get an ‘additional thrill’ of having an elephant put his trunk inside the jeep and all over them. This is a well-known fact, and there are several video clips on You Tube clearly showing Safari operators holding out their hand with food and encouraging Gemunu closer.

Now this may give some additional thrills to visitors to have a wild elephant touch them, but it is fraught with great danger. True, to this day Gemunu has not really harmed or attacked anyone, but for those who know elephant behaviour this is a time bomb waiting to go off. It will only take a frightened visitor to make a wrong move, that will anger the elephant and he could then wreak havoc, causing damage to the jeeps and even lives.

So Gemunu has become somewhat of a popular ‘icon’ at Yala, albeit a rather dubious one.

Elephants are very intelligent animals and therefore can learn certain behaviours very quickly, especially if they give positive reinforcement. This is why elephants, even when they are relatively older, can be tamed and taught to carry out various commands and even perform certain ‘tricks’.

In Gemunu’s case it is the positive reinforcement of receiving juicy tit bits from his ‘raids’ on vehicles that has made him get used to this habit

So it was a bit of a shock when news started coming through that Gemunu had broken one of his tusks in an altercation with another elephant.

As indicated earlier when in musth mature bull elephants can spar and sometimes even fight to establish their superiority over another male. It is not known if Gemunu was in musth when this happened, as the information is rather sketchy. One version has it that he had been in an altercation with two other tuskers, named as Sando (a tusker from Block 11) and Perakum.

In Gemunu’s case as is evident the entire tusk has broken off from the root itself, leaving no residual part of the tusk.

Broken tusks

Broken tusks

Broken tusks are not uncommon in elephants, who can lose them not only in altercations with other males, but also during natural movements, such as digging, excavating for water, and removing bark from trees.

When a tusk breaks off at the root itself (as in the case of Gemunu) haemorrhage may occur if the pulp is exposed, and there could be danger of secondary infection. Right now Gemunu seems to be doing fine after breaking his tusk, back to his familiar antics with the jeeps.

The senior veterinary surgeon of the Elephant Transit Home at Uda Walawe confirmed to me that Gemunu has to be closely monitored to see if there is any infection. There are also several examples where elephants’ tusks have been broken, but a mass of ivory has subsequently been deposited in the pulp cavity, resulting in the pulp becoming naturally sealed off from the external environment.

Now while tusks are basically the incisors of the elephant it is interesting to note that if a tusk is not broken off at its root, then the tusk will continue to grow.

The most famous example of this was in the case of the late ‘Walawe Raja’ (loosely translated as ‘King of Uda Walawe’) whom the author ‘knew’ well during the period he was conducting his research at the Uda Walawe National Park.

Raja was the parks most treasured exhibit, the majestic tusker in the prime of its life, who frequented the park. Raja was usually sighted during the drought period, from around July to October each year, when he appeared suddenly, to spend about three to four months in the park. Often he was in musth, and spent most of his time searching out receptive females in herds. During the balance period of the year no one really knew where he disappeared to. In all probability, he wandered out of the northern side of the park towards Balangoda and Hambegamuwa region. He also regularly carried injuries from his forays outside the park, which the resident veterinary surgeon diligently treated.

He was also the star of the BBC wildlife film ‘The Last Tusker’, and was featured in the Natural History New Zealand film production of ‘Between Two Worlds’, aired on Discovery Channel

In late 2010 when Raja suddenly went missing, my son Dimitri and I mounted a search for the majestic animal, supported by several well-wishers and donors. For over three months we searched outside of the north eastern areas of the park, tracking down leads of possible sightings. It was frustrating work and there were many false alarms, with hopes raised sometimes, only to be dashed to the ground soon after.

With a heavy heart we called off our search in early in 2011, and concluded that the majestic Raja was no more. Raja was never sighted again.

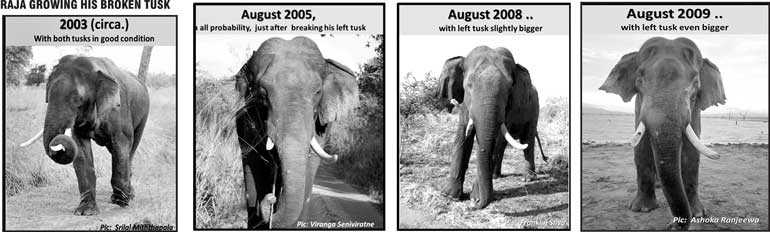

The most interesting aspect during Raja’s ‘reign’ of the park was that he broke off his left tusk around 2005. But unlike in the case of Gemunu, the tusk did not break at the root but midway, leaving a stump protruding. After a few years we noticed that it was slowly growing back. It was indeed a surprising phenomenon, which I did not know about at that time, and had to get confirmation from several elephant experts around the world.

Conclusion

Hence, although Gemunu seems to be back to his old haunts after losing his tusk, he has to be carefully monitored to see if any infection is setting in the exposed root. The DWC needs to carefully keep an eye on this.

He is too precious a celebrity and larger-than-life icon for Sri Lanka wildlife to lose.