Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Saturday, 26 May 2018 00:44 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

The news that the Peradeniya University has set up a Palm-leaf Conservation Unit took me back a few years to a visit made to the Suriyagoda temple near Kiribathkumbura close to Peradeniya. It is the temple where Velivita Sri Saranankara Sangharaja Thera got ordained as a 16-year-old young lad in 1714 CE.

We were on an assignment from the Buddhist Publication Society (BPS) planning a book for the 250th anniversary (2003) of the restoration of ‘Upasampada’ – higher ordination – initiated by the Sangharaja Thera. Our team – photographer Sarath Perera, art director Somachandra Peiris and myself – started the project with this visit.

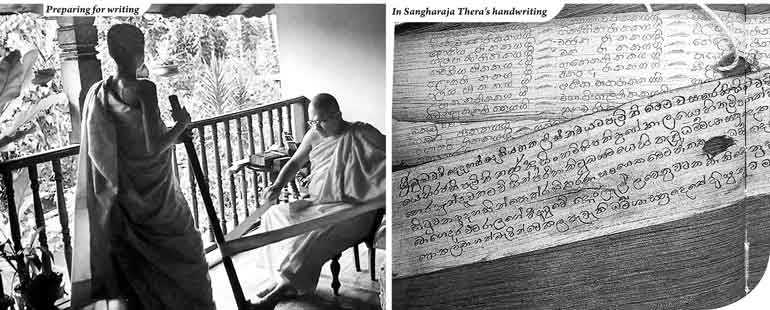

We found the monks at the temple extremely careful and vigilant about visitors because of a few bad experiences they have had, with an unknown gang trying to rob the stock of ola (palm leaf) texts used by the Sangharaja Thera and some written by him. Once the monks were convinced of our credentials they decided to show us the valuable manuscripts. We were taken into a room kept locked the whole time and in a big cupboard was the Sangharaja Thera’s collection.

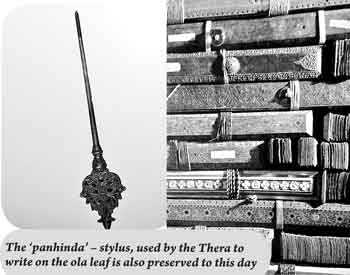

The ‘panhinda’ – stylus – used by the Thera to write on the ola leaf is also preserved to this day. Most of the other things used by him are exhibited at the Sangharaja Museum at Malwatta Viharaya.

How ‘puskola’ is made

The main material used for writing for centuries was the tender leaf of the Talipot palm (Corypha umbraculifera). The leaf once boiled, dried and prepared for writing is called ‘puskola’.

One time Archaeological Commissioner C E Godakumbura in a booklet titled ‘The Literature of Ceylon’ (1963) has this brief explanation of the ‘puskola’: “Mature leaves crudely prepared are used for writing documents of a temporary nature like medicinal prescriptions. Letters are scratched on the palm leaf with a stylus, after which charcoal powder is spread on the leaf; then an oil is smeared on the surface of the leaf and rubbed down. During this process the charcoal gets into the scratches made by the stylus and makes the writing visible. The leaves of a book are secured together by passing a string through a hole. A pair of wooden boards serve as covers.”

Former Director of National Archives Harischandra de Silva gives a detailed extract in his book ‘Printing and Publishing in Ceylon’ (1972): “This writing material, prepared from the tender leaf of the Talipot palm, is obtained from its opened leaf bud, about ten to twenty feet in length and which consists about eighty to a hundred leaflets. The midrib of each leaflet is removed and the blades are rolled up. These roles known as ‘Vattu’ are put into a large vessel of water and boiled for a couple of hours over a slow fire. The rolls are then taken out and left in the  open for three consecutive days. The next process is to smoothen and polish the leaf-blades by repeatedly running them over the smooth surface of a wooden cylinder for which locally a ‘molgaha’ or pestle is utilised. During the process of smoothening, each leaf-blade is weighted at one end. When the process of smoothening is completed the leaves are cut into the conventional sizes, with length varying from 6 inches to 32 inches, and the width from 2 inches to 2¾ inches. The punch-holes in each leaf are executed with a heated iron rod, and these are required for passing the ‘poth-lanuva’ or cord for holding together the leaves of a palm-leaf manuscript. “The next step in the process of preparation, is to press together tightly the punched leaves, and their sides and ends are singed with a hot iron so as to make all the leaves uniform in size. This process preserves the leaves from the formation of mildew and protect them from the attacks of insects. All the leaves in a volume are assembled between two book covers or ‘Kamba’, and a strong cord is passed through the punch-holes to hold the leaves and covers together and the manuscript is securely tied up with the same cord. Book covers are made of either wood or metal. Wooden covers are usually painted with colourful decorative work. Metal covers are ornamented with incised decorations and sometimes set with sparkling gems.”

open for three consecutive days. The next process is to smoothen and polish the leaf-blades by repeatedly running them over the smooth surface of a wooden cylinder for which locally a ‘molgaha’ or pestle is utilised. During the process of smoothening, each leaf-blade is weighted at one end. When the process of smoothening is completed the leaves are cut into the conventional sizes, with length varying from 6 inches to 32 inches, and the width from 2 inches to 2¾ inches. The punch-holes in each leaf are executed with a heated iron rod, and these are required for passing the ‘poth-lanuva’ or cord for holding together the leaves of a palm-leaf manuscript. “The next step in the process of preparation, is to press together tightly the punched leaves, and their sides and ends are singed with a hot iron so as to make all the leaves uniform in size. This process preserves the leaves from the formation of mildew and protect them from the attacks of insects. All the leaves in a volume are assembled between two book covers or ‘Kamba’, and a strong cord is passed through the punch-holes to hold the leaves and covers together and the manuscript is securely tied up with the same cord. Book covers are made of either wood or metal. Wooden covers are usually painted with colourful decorative work. Metal covers are ornamented with incised decorations and sometimes set with sparkling gems.”

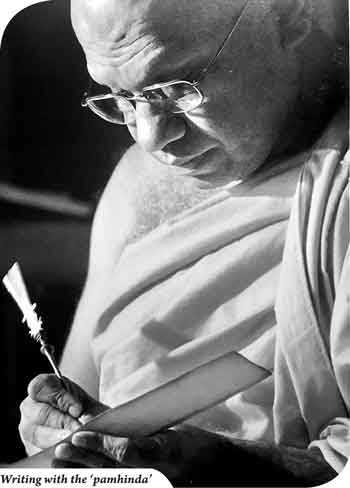

A senior monk in the Malwatta Maha Viharaya, Venerable Kulugammana Dhammrakkhita Thera who guided us in planning the publication, had stocks of ola leaves preserved for use. With the help of a young monk he prepared the leaves to show us the process of writing using a stylus. The photographs (used for this article) were used in the publication, ‘The Great Revival’ which may be available at the BPS bookshop in Kandy.

Jataka Potha kept as door plank

A prized possession at the Suriyagoda temple collection is the copy of the ‘Pansiya Panas Jataka Potha’ – collection of 550 Jataka tales – used by the Sangharaja Thera. How he found it is a fascinating story which he has written in his own handwriting. It says: “In the year 2249 Buddhist Era, during the reign of King Narendrasinghe, at a time when I, Velivita Saranankara Thera from Tumpane, was attempting to revive the Dhamma and the knowledge, having seen this book of Jataka tales being used as the door plank of the paddy barn in the house of Vilbagedera Rala, obtained it by replacing it with a door plank made from a forest tree. May it be known that I recorded this fact for the benefit of the future generations who will then get an idea of the progress made of the Dhamma and the knowledge at the time.”